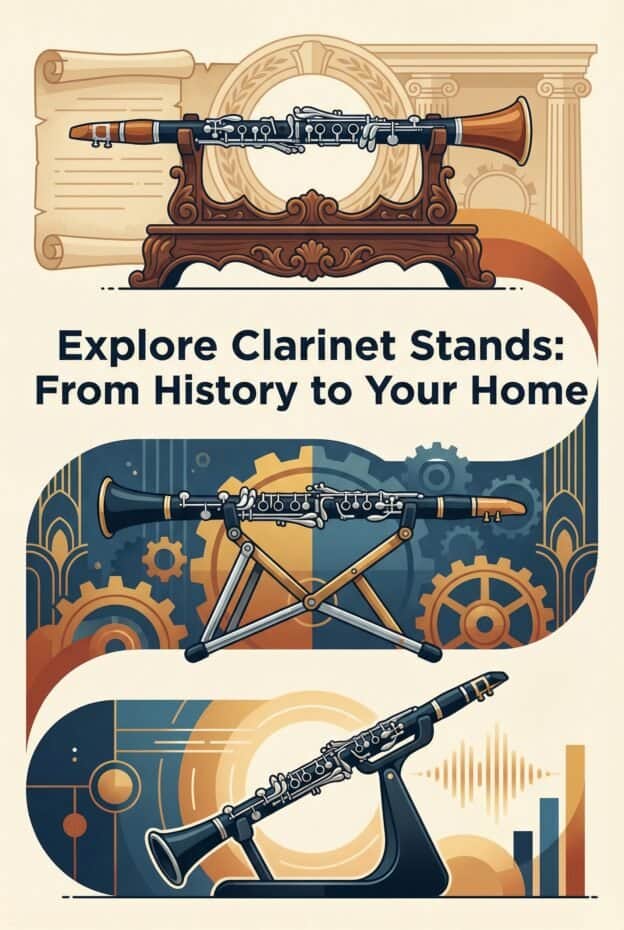

Early clarinet stands used simple wooden pegs, often fixed into heavy wooden bases. During the 19th century, wrought iron and brass stands became more decorative, echoing Victorian furniture. The Industrial Revolution introduced aluminum and steel, enabling lighter, portable, mass-produced stands. By the late 20th and 21st centuries, foldable, adjustable multi-instrument stands became standard for modern clarinetists.

Why Clarinet Stands Matter: Function, Safety, and Stage Practice

Clarinet stands look simple, but they sit at the intersection of instrument safety, stage efficiency, and performance practice. A well designed stand protects the clarinet body, tenons, and bell from impact, while a poor design can concentrate stress on delicate joints or tip over during a performance or rehearsal.

Historically, many clarinetists simply laid instruments on tables or chairs. As concert halls grew and stage movement increased, the need for a secure vertical support became clear. Stands allowed faster instrument changes, reduced risk of rolling damage, and kept keywork away from crowded surfaces and wandering feet in orchestra pits.

Clarinet anatomy shapes stand design. The bell flare, lower joint, and tenon corks are frequent contact points. Early single peg stands often engaged only the bell interior, which created use on the lower joint. Modern designs distribute weight along the bell and lower body, using padding to avoid scratches and to reduce point pressure on the bore.

For players, the outcome is practical. A stable stand means quicker transitions between B-flat and A clarinets, safer doubling with saxophone or bass clarinet, and less mental load about where to place the instrument. For curators and restorers, stands also influence how historical clarinets are displayed and preserved in museums and archives.

Timeline: From Early Wooden Pegs to Modern Foldable Stands

Clarinet stand history follows broader changes in furniture, metalwork, and stage practice. While documentation is patchy, we can sketch a practical timeline that helps musicians, designers, and restorers understand how form followed function across several centuries of clarinet playing.

Early period (pre-19th century): Surviving evidence suggests simple, locally crafted solutions. These included wooden pegs set into heavy blocks or integrated into music stands. Many clarinetists still relied on tables or cases, so dedicated stands were rare and often custom built by cabinetmakers or instrument makers.

19th century: As clarinets gained orchestral prominence, more specialized stands appeared. Wrought iron and brass became common, often combined with turned or carved wooden bases. Designs mirrored Victorian furniture, with scrollwork, floral motifs, and tripod or quadruped bases that echoed parlor and salon decor.

Industrial Revolution turning point: The late 18th and 19th centuries brought machine tools, standardized tubing, and more consistent screws and fittings. Clarinet stands began to use lighter metal rods, threaded joints, and modular parts. This shift made portable, repeatable designs possible, instead of one-off artisanal pieces.

20th century: Aluminum and mild steel entered the picture. Foldable legs, telescoping sections, and detachable pegs became standard. Manufacturers targeted traveling musicians, so weight and compactness mattered. Rubber and plastic caps appeared on pegs to protect the bell interior and improve grip.

Modern era (late 20th to 21st century): Today, clarinet stands include ultra-light collapsible models, multi-instrument racks, and hybrid systems that mount inside cases. Designers focus on fast setup, secure bell support, and compatibility with B-flat, A, and sometimes E-flat clarinets. Some stands adapt for oboe or flute, reflecting the needs of doublers.

Materials & Construction by Era (Wood, Wrought Iron, Brass, Aluminum, Steel)

Clarinet stand materials track advances in woodworking and metalworking. Each era brought different strengths and weaknesses in weight, stability, corrosion resistance, and interaction with the clarinet's wood and keywork. Understanding these helps guide restoration and modern design choices.

Wood in early and 19th century stands: Early stands often used hardwoods such as beech, oak, or walnut for bases, with a simple turned peg. Joinery could be as basic as a glued dowel or as refined as a threaded wooden tenon. Heavy bases provided stability, but unpadded wood-on-wood contact risked scratching the bell interior.

Wrought iron: In the 19th century, wrought iron allowed slender yet strong uprights and decorative scrolls. Blacksmiths forged tripod feet and curled embellishments. These stands were durable but prone to corrosion, especially in damp halls. Thin iron pegs without padding could mark softer clarinet wood or chip fragile bell rims.

Brass: Brass introduced a warmer color and easier machining. Many Victorian and early 20th century stands used brass rods and fittings with cast or spun bases. Brass resisted rust but still tarnished, which could transfer discoloration to unprotected wood. Makers sometimes added felt or leather collars to soften contact points.

Aluminum: With the 20th century came aluminum tubing and cast components. Aluminum reduced weight dramatically, ideal for touring musicians. However, very light stands needed wide leg spreads or clever geometry to avoid tipping. Anodizing and paint helped prevent oxidation, while rubber and plastic collars protected clarinet bells.

Steel: Mild steel and later high strength alloys allowed thin yet rigid legs and pegs. Combined with plastic or composite hubs, steel stands could fold compactly while remaining stable. Powder coating improved corrosion resistance. Designers used molded rubber caps and foam sleeves at contact points to cushion the clarinet.

Across all eras, the interface between stand and clarinet remained critical. Felt, leather, cork, and later synthetic foams appeared as padding materials. Restoration literature often cites felt and leather as historically plausible choices, although specific recipes and suppliers are rarely documented and merit targeted archival research.

Design Features & Aesthetics: Decorative Traditions and Furniture Styles

Clarinet stands never existed in isolation. Makers borrowed visual language from furniture, lighting, and decorative arts. Understanding these influences helps date historical stands and guides designers who want period appropriate replicas that still function safely for modern instruments.

In the early period, stands were often plain, reflecting workshop pragmatism. A simple turned peg in a block of wood matched the utilitarian benches and music desks of small ensembles. Ornament was minimal, and any decoration usually came from the wood grain itself or a basic lathe profile.

By the 19th century, especially in Victorian England and France, clarinet stands echoed parlor furniture. Wrought iron models featured scrolls, leaves, and rosettes similar to lamp stands and plant holders. Wooden bases might include carved feet, fluted columns, or inlaid veneers that matched music cabinets and piano stools.

Brass stands often adopted neoclassical or Art Nouveau motifs. Round, weighted bases with beaded edges, flared columns, and stylized floral elements were common. These stands functioned as both tools and display pieces, signaling the owner's taste and the instrument's status in the household or salon.

With the Industrial Revolution and into the 20th century, aesthetics shifted toward function. Straight lines, minimal ornament, and standardized parts reflected broader trends in industrial design. Companies prioritized stackability and shipping efficiency, so bases became flatter, legs foldable, and decorative flourishes rare.

Modern stands embrace a technical look: exposed screws, molded plastic hubs, and visible steel or aluminum tubing. Some boutique makers, however, revisit historical aesthetics, creating stands that visually match period clarinets or historical performance settings while quietly incorporating modern safety features like padded pegs and wider bases.

Workshop Notes & Techniques: Custom Crafting, Single-Peg Supports, and Stability Lessons

For luthiers, woodworkers, and metalworkers, clarinet stands offer a compact project that combines joinery, ergonomics, and historical awareness. Even without full archival measurements, certain workshop principles can guide safe, historically informed construction or restoration of single peg and multi leg designs.

Single peg geometry: Traditional stands often used a single vertical peg that inserted into the clarinet bell. To avoid excessive use on the lower joint, the peg diameter should closely match the bell throat, with a gentle taper and generous padding. The peg must be long enough to prevent wobble but not so long that it contacts the upper joint.

Base design and footprint: Stability depends on the relationship between clarinet center of gravity and base footprint. A heavy wooden disk or tripod with feet extending at least the bell diameter in three directions greatly reduces tipping. Historical stands sometimes underestimated this, leading to the wobble issues described in period accounts.

Joinery and fastenings: Early wooden stands used glued mortise and tenon joints or threaded wooden dowels. Metal stands used rivets, brazed joints, or threaded collars. For restorations, matching the original method preserves authenticity, while discreet reinforcement, such as hidden screws or epoxy sleeves, can improve safety for actual use.

Padding materials: Felt, leather, and cork are historically plausible and gentle on grenadilla and boxwood. Modern foams and rubber sleeves add grip but can off-gas or stick over time. When retrofitting a historical stand, a thin leather wrap over a wooden or metal peg offers a reversible, non invasive solution that respects the original object.

Finish and corrosion control: Shellac, oil, or wax finishes suit wooden components and align with period furniture practice. For wrought iron and steel, careful rust removal followed by clear wax or traditional black paint protects the metal. Brass can be cleaned lightly, but over polishing may erase tool marks that help date the stand.

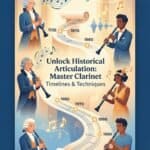

Industrialization and Portability: How Mass Production Changed Stand Design

The Industrial Revolution reshaped clarinet stands by introducing standardized parts, machine threading, and new alloys. This shift paralleled changes in instrument manufacture, where makers like Buffet and Selmer adopted more uniform keywork and bore dimensions, enabling accessories to fit a wider range of clarinets.

Mass production allowed stands to move from bespoke workshop items to catalog products. Companies could sell stands alongside cases, reeds, and ligatures. Steel and aluminum tubing made it possible to create collapsible legs that folded against a central hub, reducing volume for shipping and travel without sacrificing stability.

Threaded joints became common. Players could screw pegs into bases, swap pegs for different instruments, or replace damaged parts without discarding the entire stand. This modularity encouraged multi instrument designs, where a single base supported several pegs for B-flat, A, and E-flat clarinets or related woodwinds.

Portability also changed stage practice. Touring orchestras and wind ensembles needed gear that packed into trunks and later into airline cases. Lightweight stands with telescoping sections and detachable components met that need. The tradeoff was reduced decorative appeal, as ornament gave way to functional, repeatable forms.

By the late 20th century, injection molded plastic hubs and rubber feet became standard. These components simplified assembly and reduced cost, while also improving grip on smooth stage floors. Industrialization thus not only lowered prices but also raised the baseline safety and usability of clarinet stands for everyday players.

Case Study – Historical Associations (including Martin Freres and archival context)

Clarinet stands intersect with the history of specific instrument makers, including French firms active in the 19th and early 20th centuries. While many stands were anonymous, some were sold through music houses that also distributed clarinets, creating indirect associations valuable to historians and curators.

In France, shops that handled instruments by makers such as Martin Freres often offered accessories sourced from local metalworkers and cabinetmakers. Surviving catalogs and trade advertisements occasionally depict stands alongside clarinets, even when the stands themselves carry no maker stamp. These images help date design trends and materials.

Museum collections in Paris, London, and Brussels sometimes preserve clarinets and stands as ensembles, even if the stand was added later. When a Martin Freres clarinet appears with a wrought iron or brass stand, curators must decide whether to treat the pair as a historical unit or as separate objects that simply shared a performance context.

For restorers, understanding these associations matters. A late 19th century French clarinet displayed on a mid 20th century tubular steel stand sends mixed signals about period practice. A more appropriate choice might be a wooden base with a brass or iron peg, echoing the decorative language of the instrument's original era.

Common Gaps in the Record: Missing Measurements, Patents, and Maker Attributions

Research on clarinet stands faces several frustrating gaps. Unlike clarinets themselves, stands rarely carry serial numbers or maker stamps. Dimensions were seldom documented, and patents focused more on instrument mechanisms than on accessory furniture, leaving designers and historians to reconstruct details from scattered evidence.

Measurements are a primary challenge. Few museums publish precise dimensions of historical stands, and many catalog entries simply note “metal stand” or “wooden support”. For replication, makers must infer peg diameter, base thickness, and leg spread from photographs or from direct access to objects, which is not always possible.

Patent records offer partial help. Some 19th and early 20th century patents describe general instrument supports, but they often lack clarinet specific details. Drawings may show a bell on a peg, yet omit critical information like padding materials or exact angles. Cross referencing patents with surviving examples remains an open research task.

Maker attribution is equally difficult. Many stands were produced by generic metalworking shops or furniture makers, then sold through music retailers. Even when a stand appears with a labeled clarinet by a known maker, there is no guarantee the two originated together. Provenance research must therefore rely on stylistic comparison and documentary context.

For modern researchers, systematic documentation can help close these gaps. Recording full measurements, materials, and construction details for each stand encountered, along with high resolution photographs, builds a comparative database. Over time, patterns in leg profiles, peg shapes, and decorative motifs may reveal regional schools or workshop traditions.

How to Choose or Adapt a Clarinet Stand Today (safety, portability, multi-instrument use)

Choosing a clarinet stand today means balancing historical awareness with modern safety and portability. Whether you are a performer, curator, or designer, a structured approach helps ensure that the stand protects the instrument and suits its context, from concert stage to museum display.

Step 1: Match stand design to clarinet anatomy

Start by considering how the stand contacts the clarinet. For performance use, a bell inserted over a padded peg is standard. Ensure the peg diameter fits comfortably inside the bell without forcing the wood or stressing the rim. Avoid designs where the peg reaches the lower joint tenon or keywork.

For historical or fragile instruments, consider supports that cradle the bell exterior or support the lower joint body instead of inserting deeply into the bore. Soft padding at all contact points is important. Check that keys, especially low E and F, do not rest against any part of the stand when the clarinet is in place.

Step 2: Evaluate stability and base footprint

Next, examine the base. A tripod or quadruped design with a wide footprint provides better stability than a narrow disk, especially on crowded stages. Test for wobble by gently nudging the clarinet from different directions. If the stand rocks or tips easily, it is unsuitable for performance use.

On slippery floors, rubber feet improve grip. For museum displays, a heavier base may be preferable, even if it sacrifices portability. When adapting a historical stand, discreetly enlarging the base or adding hidden weight can improve safety while preserving the original visual profile.

Step 3: Consider portability and multi-instrument needs

For active musicians, portability is often decisive. Foldable legs, detachable pegs, and compact folded dimensions make travel easier. If you play both B-flat and A clarinet, or double on E-flat or oboe, a multi peg stand reduces clutter and speeds instrument changes during concerts and rehearsals.

Check how quickly the stand assembles and disassembles. Complex locking mechanisms may fail under pressure in dim orchestra pits. Simple, strong designs with clear tactile feedback are usually more reliable. For pit work or touring, many players carry a backup stand in case of mechanical failure.

Step 4: Maintenance and troubleshooting for modern and historical stands

Regular maintenance keeps stands safe. Inspect metal parts for corrosion, especially on older wrought iron or brass models. Replace or rewrap padding that has hardened, cracked, or become sticky. Tighten screws and check that telescoping sections lock securely without slipping under load.

If a stand wobbles, investigate the cause. Loose joints may need shims, threadlocker, or replacement hardware. Narrow bases can sometimes be stabilized by adding a wider auxiliary platform. For historical stands, consider using them only for display, while relying on modern stands for actual playing sessions.

Key Takeaways

- Clarinet stands evolved from simple wooden pegs to industrially produced, foldable metal designs that prioritize portability and safety.

- Material choices, from wood and wrought iron to aluminum and steel, shape both aesthetics and how the stand interacts with clarinet anatomy.

- Historical documentation of stand dimensions and makers is sparse, so careful measurement and photography are important for research and replication.

- Modern players should prioritize stable bases, well padded contact points, and designs that match their performance and multi instrument needs.

- Historical stands often suit display better than daily use, but thoughtful adaptation can honor their style while protecting valuable instruments.

FAQ

What is clarinet stands?

Clarinet stands are support devices that hold a clarinet upright when it is not being played. They typically use a central peg or cradle that engages the bell or lower body, combined with a stable base, to protect the instrument from tipping, rolling, or impact damage during rehearsals, performances, or display.

How did clarinet stand designs change during the Industrial Revolution?

During the Industrial Revolution, clarinet stands shifted from heavy, decorative wooden and wrought iron pieces to lighter, standardized metal designs. Machine made tubing, threaded joints, and modular components enabled foldable legs, interchangeable pegs, and mass production, making stands more portable and affordable for working musicians.

Are historical clarinet stands safe to use with modern instruments?

Many historical clarinet stands are not fully safe for regular use with modern instruments. Narrow, unpadded pegs and small bases can stress the bell and increase tipping risk. These stands are often better suited to display, while modern stands with wider footprints and improved padding handle daily performance duties.

How do I choose a clarinet stand for performance versus practice?

For performance, prioritize stability, quick setup, and compatibility with multiple instruments if you double. A compact, foldable stand with a wide base and good padding works well. For practice, weight and portability matter less, so you can use a heavier, more permanent stand that stays in your studio or teaching space.