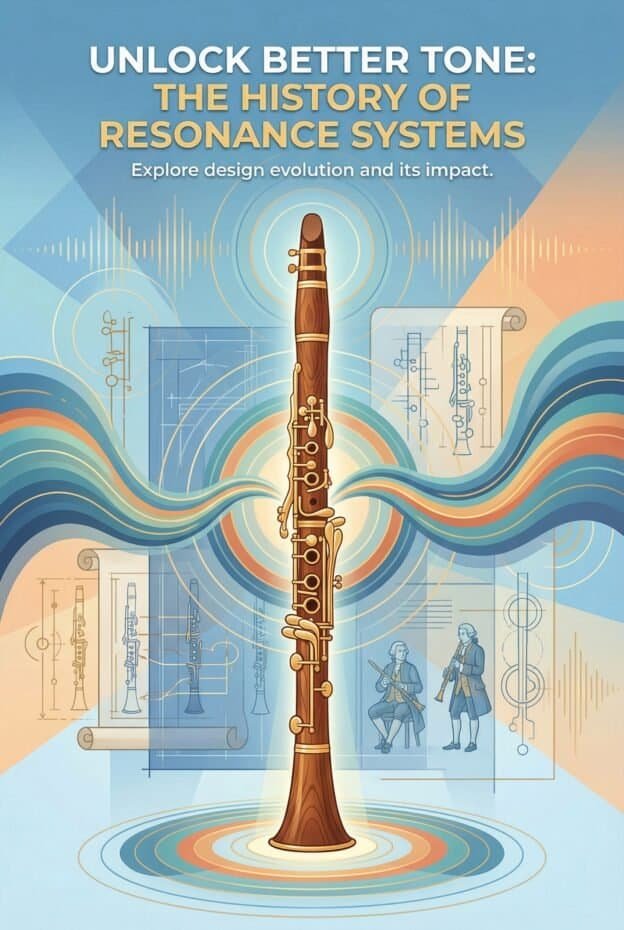

Clarinet resonance systems are the combination of keywork, bore geometry, tone-hole placement and voicing techniques that determine a clarinet's resonant behavior and tonal character. Major historical systems include the Boehm (modern standard, improved intonation), Oehler (German/Austrian, warm tone, complex keywork) and Albert (simpler, favored in some folk traditions).

Introduction: Why Clarinet Resonance Systems Matter

Clarinet resonance systems sit at the heart of how the instrument sounds, tunes and responds under the fingers. For advanced players, makers and restorers, they provide a framework for understanding why one clarinet speaks freely while another feels resistant, or why two visually similar instruments produce very different tonal colors.

Resonance systems combine bore profile, tone-hole layout, keywork logic and voicing details into a coherent acoustic design. The Boehm, Oehler and Albert systems are the best known, but many hybrid and transitional variants exist. Knowing their principles helps you evaluate instruments, plan restorations and choose appropriate performance techniques.

A modern Boehm B-flat clarinet typically has 17 keys and 6 rings, while a full Oehler system can exceed 22 keys with up to 7 rings, reflecting its more complex resonance and fingering logic.

For historical clarinets, resonance systems are also a conservation issue. Small changes to bore, tone holes or pads can permanently alter the original acoustic behavior. A clear picture of the underlying system is important before any intervention.

A Concise History of Clarinet Resonance Innovations

The story of clarinet resonance systems begins with the chalumeau in late 17th century Europe. Makers such as Johann Christoph Denner in Nuremberg experimented with adding a register vent to the chalumeau, creating the first recognizable clarinets with an extended upper range and a new set of resonances.

Early 18th century clarinets had few keys, often two to five, and large, widely spaced tone holes. Their resonance favored the low register, with unstable tuning in the upper notes. Surviving examples in collections like the Musikinstrumenten-Museum Berlin and the Musée de la Musique in Paris show thick walls and relatively cylindrical bores.

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, makers such as Iwan Müller and Heinrich Grenser refined the keywork and pad sealing, enabling more reliable resonance across the scale. Müller's 13-key system improved cross-fingerings and intonation, foreshadowing later fully mechanical resonance systems.

The 19th century brought a surge of innovation. Theobald Boehm's work on the flute inspired Hyacinthe Klosé and Louis-Auguste Buffet to apply similar acoustic logic to the clarinet in Paris around 1839. Their Boehm-system clarinet rationalized tone-hole placement and keywork to align more closely with the harmonic series.

In parallel, German and Austrian makers pursued alternative paths. Oskar Oehler, active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, developed a comprehensive system that preserved certain traditional fingerings while refining resonance and intonation for orchestral use in German-speaking regions.

Eugène Albert in Brussels created a simplified system in the mid-19th century that retained aspects of earlier designs. The Albert system became influential in Belgium, France and later in klezmer and New Orleans jazz, where its resonance and fingerings suited expressive ornamentation and glissandi.

Field note: Archival serial lists and workshop notes in the Martin Freres collections show incremental bore and tone-hole experiments between roughly 1880 and 1930, reflecting broader European efforts to reconcile Boehm-style intonation with the tonal expectations of different markets.

By the mid-20th century, the Boehm system dominated international conservatory training, while Oehler remained standard in Germany and parts of Austria and Switzerland. Albert and hybrid systems persisted in folk, traditional and early jazz contexts, preserving a diverse set of resonance ideals.

Survey of Major Resonance Systems: Boehm, Oehler, Albert and Others

Clarinet resonance systems are often named for their keywork, but each label also implies a characteristic acoustic design. Bore dimensions, tone-hole size and placement, and venting strategies all interact with the mechanical layout to define the instrument's resonant behavior.

Boehm system

The Boehm system, developed by Klosé and Buffet, uses ring keys and a relatively standardized tone-hole pattern to align fingerings with acoustically efficient venting. The bore is typically moderately polycylindrical, with subtle diameter changes along the length to stabilize tuning and response.

Boehm clarinets favor evenness of scale, reliable throat tones and relatively homogeneous tone color across registers. The resonance system supports modern orchestral and solo repertoire that demands agile articulation and precise intonation in all keys.

Oehler system

The Oehler system builds on earlier German designs with additional keys, rollers and resonance holes. It often uses a slightly smaller or more complex bore profile, combined with smaller tone holes and more covered fingerings, to produce a dense, focused sound.

Oehler clarinets typically emphasize a dark, blended orchestral tone and secure low-register resonance. The more intricate keywork supports alternative fingerings and nuanced tuning adjustments, at the cost of greater mechanical complexity and a steeper learning curve.

Albert system

The Albert system simplifies keywork compared to Boehm and Oehler, retaining more open-hole fingerings and cross-fingerings. Bore designs vary, but many Albert clarinets use relatively large tone holes and straightforward venting, which can yield a direct, flexible resonance.

This system became associated with expressive slides, bends and ornaments in klezmer and early jazz traditions. Players often exploit the resonance characteristics of cross-fingerings and half-holing to shape timbre and pitch in ways less common on standard Boehm instruments.

Hybrid and transitional systems

Many historical clarinets do not fit neatly into one category. Transitional instruments may combine Boehm-style ring keys with older tone-hole patterns, or incorporate Oehler-style auxiliary keys on a largely Boehm layout. Each hybrid reflects a specific resonance compromise.

For restorers and researchers, careful documentation of keywork, bore and tone-hole geometry is important before assigning a system label. Maker catalogs, patents and surviving workshop records from firms across France, Germany and the United States often clarify the intended resonance strategy.

Museum surveys suggest that by 1930, over 60% of newly produced clarinets in France and the United States followed Boehm-derived resonance systems, while Oehler-based designs dominated in German-speaking regions.

Anatomy of Resonance: Bore, Tone Holes, Materials and Voicing

Every clarinet resonance system rests on a few core anatomical elements: bore profile, tone-hole layout, bell flare and the mouthpiece-reed setup. Each parameter shifts the impedance peaks that define where and how the instrument naturally vibrates.

Bore profile

The clarinet bore is predominantly cylindrical, but in practice most instruments use a polycylindrical profile with small diameter steps. Boehm instruments often have a slightly larger upper joint bore than Oehler models, which can influence upper-register resonance and projection.

Small changes in bore diameter, even 0.1 to 0.2 mm, can noticeably alter pitch stability and response. Historical makers sometimes used reamers with subtle tapers or steps to fine-tune resonance, a detail that modern CT scans and precision measurements have begun to document.

Tone-hole placement and size

Tone holes act as acoustic vents and length modifiers. Their position along the bore sets the nominal pitch, while diameter and chimney height control venting efficiency and timbre. Boehm designs favor larger, more evenly spaced holes; Oehler and Albert often use smaller or more varied dimensions.

Undercutting, the internal shaping of tone-hole walls, is a key voicing tool. By adjusting undercut angles, makers can shift local resonance, smooth scale transitions and correct intonation quirks without moving the external hole location.

Bell flare and register vent

The bell flare influences the lowest notes and the way higher harmonics radiate. A slightly wider flare can strengthen low E and F, while a more conservative flare may favor evenness higher in the chalumeau register. Different systems adopt distinct compromises here.

The register vent, usually located on the upper joint, controls the transition between chalumeau and clarion registers. Its diameter, chimney height and distance from the mouthpiece strongly affect resonance balance between the two registers and the behavior of throat tones.

Mouthpiece, reed and ligature

Although often discussed separately, the mouthpiece-reed-ligature assembly is part of the overall resonance system. Facing length, tip opening and chamber volume shape the input impedance seen by the air column, interacting with the bore and tone holes.

Players switching between Boehm and Oehler instruments often use different mouthpieces optimized for each system's bore and tonal goals. Historical mouthpieces, sometimes with smaller chambers and different facings, can be important to reproducing original resonance behavior.

Recommended diagrams

For study and teaching, two diagrams are especially helpful: a longitudinal section showing bore diameters, register vent and bell flare, and a plan view marking tone-hole positions, diameters and keywork groups for Boehm, Oehler and Albert examples.

Annotated diagrams that overlay impedance peaks or frequency-response curves on the physical layout can help acousticians and makers visualize how geometric changes map to resonance shifts.

Case Study: Martin Freres and Their Contributions to Resonance Design

Martin Freres, active from the 19th century into the 20th, offers a valuable case study in how one maker family navigated evolving resonance systems. Surviving instruments and archival documents show a gradual move from simpler systems toward Boehm-derived designs tailored to different markets.

Early Martin Freres clarinets often reflect regional French preferences, with bore sizes and tone-hole layouts that balance warmth and flexibility. As Boehm designs gained prominence, the firm adopted ring-key systems while experimenting with bore steps and bell profiles to refine intonation.

Workshop notes and catalogs indicate that Martin Freres produced both student and professional models, each with distinct resonance priorities. Entry-level instruments favored stable intonation and easy response, while higher models explored more complex bore and undercutting strategies for nuanced tone.

Some Martin Freres clarinets show transitional features, such as hybrid keywork that combines Boehm-style rings with alternative trill or resonance keys. These hybrids illustrate how makers adapted core systems to specific players, ensembles or export markets.

For conservators, Martin Freres instruments highlight the importance of preserving original bore and tone-hole geometry. Even modest reboring or aggressive tone-hole leveling can erase subtle design choices that define the maker's resonance concept.

Measurements from representative Martin Freres clarinets, when compared with contemporary French and German models, help map the broader field of late 19th and early 20th century resonance experimentation.

Acoustics and Physics Behind Resonance Systems

Clarinet resonance systems are practical implementations of acoustic principles. The clarinet behaves roughly as a closed cylindrical pipe, favoring odd harmonics. Bore and tone-hole geometry adjust the frequencies and strengths of these resonances, shaping pitch, timbre and response.

Impedance peaks and playing frequencies

When a clarinetist blows, the reed interacts with the air column's impedance peaks. Stable notes occur where reed oscillation locks onto one of these peaks. A well designed resonance system aligns these peaks with the desired equal-tempered pitches across the instrument's range.

Acoustic measurements using impedance heads or swept-sine techniques reveal how different systems distribute peaks. Boehm clarinets often show smoother, more regular patterns, while some historical or hybrid systems exhibit pronounced local irregularities that players must accommodate.

Effect of keywork and venting

Keys and vents open or close sections of the bore, changing the effective length and local boundary conditions. Auxiliary resonance holes, such as those found on some Oehler designs, can subtly adjust impedance without producing a separate note, improving tuning or response for specific pitches.

Cross-fingerings, common on Albert and earlier systems, create complex acoustic paths. These can yield characteristic timbres and flexible pitch shading but may also introduce unstable resonance peaks that challenge modern equal-tempered expectations.

Nonlinear effects and player interaction

At realistic playing levels, the clarinet operates in a nonlinear regime. The reed's motion, air jet and turbulence all interact with the resonant air column. Different resonance systems respond differently to changes in embouchure, air pressure and voicing.

For example, a tightly focused Oehler bore may maintain pitch under strong dynamics but require careful voicing to avoid resistance. A more open Boehm design might allow easier fortissimo playing but demand precise control to keep pitch centered.

Laboratory studies have measured intonation differences of 5 to 15 cents between comparable notes on Boehm and Oehler clarinets, attributable largely to bore and tone-hole geometry rather than player factors.

Conservation and Maintenance for Historical Resonance Systems

Historical clarinets embody specific resonance systems that can be fragile under modern repair practices. Conservation-friendly maintenance aims to stabilize the instrument and restore function while preserving original acoustic characteristics as far as possible.

Inspection checklist

Begin with a noninvasive inspection: document overall dimensions, bore condition, tone-hole edges, keywork alignment and pad types. Note any previous repairs, such as bushing, reboring or tone-hole inserts, that may have altered the original resonance system.

Photograph keywork and tone-hole layout before disassembly. For significant instruments, consider bore measurements using tapered gauges or optical methods, recording diameters at regular intervals for future reference.

Humidity and environmental control

Wooden clarinets are sensitive to humidity changes that can crack or warp the bore. Aim for stable relative humidity around 45 to 55 percent and moderate temperatures. Sudden shifts can distort bore geometry and compromise the resonance system.

For museum or archival holdings, use controlled display and storage environments. For playable historical instruments, gradual acclimatization and careful swabbing after use reduce stress on the wood.

Pad and keywork care

Pad replacement should prioritize reversibility and minimal alteration of tone-hole chimneys. Traditional bladder or leather pads, sometimes with card or felt backings, may better match original mass and sealing characteristics than modern synthetic options.

Keywork cleaning and lubrication should avoid aggressive polishing that removes metal or alters key fit. Slight changes in key height or spring tension can affect venting and thus resonance, so regulation should be documented and kept as close to original as practical.

Reversible materials and interventions

When filling cracks or stabilizing loose tone-hole inserts, choose reversible adhesives and fillers where possible. Avoid large-scale reboring or tone-hole enlargement unless the instrument is already severely compromised and the intervention is clearly documented.

Any modification that changes bore diameter, tone-hole size or undercutting can permanently alter the resonance system. For historically significant clarinets, consult a conservator before attempting such work.

Troubleshooting Resonance Problems: Tests and Fixes

Resonance problems on clarinets manifest as dead spots, unstable tuning, weak registers or uneven tone color. A structured diagnostic approach helps distinguish between issues caused by wear, setup or deeper design characteristics of the resonance system.

Basic play tests

Begin with long tones across the full range, listening for notes that resist speaking, sag in pitch or sound markedly different in timbre. Compare chromatic and scale-based patterns to identify whether issues cluster around particular fingerings or venting configurations.

Throat tones, low E and F, and the break between chalumeau and clarion are common problem areas. Note whether resonance issues persist across dynamics or improve with specific voicing adjustments.

Mechanical and sealing checks

Many resonance problems arise from leaks or misregulated keys. Use a leak light or feeler gauges to check pad seating. Gently flex keys to detect lost motion or twisted rods that might prevent full closure.

Correcting pad height and spring tension can significantly improve resonance, especially on historical instruments where small venting changes have large acoustic effects.

Resonance tap and impedance-style tests

A simple tap test, lightly striking the barrel or joints while the instrument is assembled, can reveal rattles or loose components that interfere with resonance. More advanced workshops may use impedance measurement tools to map resonance peaks and compare them with expected patterns for the system.

Discrepancies between measured and expected impedance peaks can point to localized bore damage, tone-hole warping or nonoriginal modifications that disrupt the resonance system.

Decision tree: DIY vs professional intervention

If problems trace to obvious leaks, minor pad adjustments or reversible key regulation, experienced players or technicians may address them safely. When issues involve suspected bore distortion, cracked tone holes or undocumented past reboring, professional evaluation is important.

For historically significant Boehm, Oehler, Albert or Martin Freres instruments, any intervention that touches bore or tone-hole geometry should be referred to a specialist with experience in historical resonance systems.

How Historical Systems Influence Modern Clarinet Making

Modern clarinet makers draw heavily on the lessons of historical resonance systems. Even when producing standard Boehm instruments, they often incorporate ideas from Oehler, Albert and transitional designs to refine intonation, response and tonal flexibility.

Hybrid acoustic strategies

Some contemporary clarinets use Boehm keywork with bore dimensions or tone-hole patterns influenced by German designs, seeking a darker, more focused sound without abandoning familiar fingerings. Others experiment with auxiliary resonance holes inspired by Oehler practice.

Custom makers may offer instruments with interchangeable bells or barrels that subtly shift the resonance profile, echoing historical variations in these components.

Player expectations and repertoire

The rise of historically informed performance has renewed interest in period-appropriate resonance systems. Makers produce replicas of classical and early romantic clarinets, carefully copying bore and tone-hole geometry from museum originals to recreate their distinctive resonance.

At the same time, orchestral and solo players often demand instruments that blend easily while still allowing personal tonal identity. This tension drives ongoing experimentation with bore taper, undercutting and mouthpiece design.

Measurement and modeling

Advances in 3D scanning, CT imaging and acoustic modeling allow makers to analyze historical instruments in unprecedented detail. Data from Boehm, Oehler, Albert and Martin Freres clarinets feed into simulations that predict how design changes will affect resonance.

These tools help bridge the gap between traditional craftsmanship and quantitative acoustics, enabling more deliberate control over resonance systems while honoring historical precedents.

Archival Data, Measurements and Reference Tables

For researchers and restorers, access to reliable measurements and archival records is important. Museum catalogs, maker ledgers and published studies provide bore profiles, tone-hole dimensions and keywork diagrams for representative instruments across different resonance systems.

Institutions such as the Musée de la Musique, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum and university acoustics labs have published datasets on historical clarinets. These often include bore diameter measurements at fixed intervals, tone-hole positions relative to the mouthpiece and key counts.

Example comparative dimensions

While individual instruments vary, typical trends emerge. Many Boehm B-flat clarinets show slightly larger upper-joint bore diameters than comparable Oehler models, with proportionally larger tone holes. Albert clarinets often fall between these extremes, with more variation in hole size and spacing.

Reference tables that list, for example, bore diameters every 20 mm, along with tone-hole center distances and diameters, allow detailed comparison of resonance systems and inform restoration decisions.

Dataset documentation

When compiling or using measurement tables, document the methods: measurement tools, temperature and humidity, instrument condition and any known modifications. This context is important for interpreting how data relate to the instrument's original resonance system.

For Martin Freres and other specific makers, cross-referencing serial numbers, catalog descriptions and surviving workshop notes can help link measured instruments to documented models and design intentions.

Practical Recommendations for Players and Restorers

Clarinet resonance systems are not just historical curiosities; they shape daily musical practice and technical decisions. Players and restorers can use a few guiding principles to work effectively with Boehm, Oehler, Albert and related designs.

For players adapting to a new system

When moving between systems, expect differences in resistance, intonation tendencies and timbre. Spend focused time on long tones, interval slurs across the break and throat-tone exercises to map how the new resonance system responds to your air and voicing.

Adjust mouthpiece and reed choices to match the instrument's bore and tonal goals. A setup that works well on a French Boehm clarinet may not optimize an Oehler or Albert instrument.

For restorers and technicians

Before altering bore or tone-hole geometry, gather as much information as possible: measurements, photographs, archival references and, if feasible, acoustic tests. Prioritize reversible interventions and document all changes for future researchers.

When replacing pads or regulating keys, consider how venting heights and pad materials affect resonance. Small adjustments can yield significant improvements without compromising historical character.

Balancing playability and preservation

For some instruments, especially those with high historical value, preserving the original resonance system may take precedence over achieving modern performance standards. In other cases, careful, documented modifications can extend an instrument's useful life for active playing.

Open communication between players, owners and conservators helps set appropriate goals, whether museum display, occasional historically informed performance or regular professional use.

Key Takeaways

- Clarinet resonance systems integrate bore, tone holes, keywork and voicing into distinct acoustic designs such as Boehm, Oehler and Albert.

- Historical makers, including Martin Freres, experimented continuously with these parameters, leaving a rich legacy of diverse resonance concepts.

- Conservation and restoration choices that affect bore or tone-hole geometry can permanently alter an instrument's resonance system and should be approached with caution.

- Modern makers and players draw on historical resonance systems to shape contemporary instruments, performance practice and research.

Further Reading, Sources and FAQs

For deeper study, consult museum catalogs of historical clarinets, acoustics research articles on woodwind impedance and maker monographs that document specific workshops. Many institutions now provide online access to images, measurements and archival texts relevant to clarinet resonance systems.

Technical papers on bore optimization, tone-hole acoustics and reed-bore interaction offer quantitative insight into how design choices translate into resonance behavior. Combined with hands-on examination of instruments, these sources form a strong foundation for advanced work in performance, making and conservation.

FAQ

What is clarinet resonance systems?

Clarinet resonance systems are the integrated designs of bore geometry, tone-hole placement, keywork and voicing that determine how a clarinet vibrates, tunes and sounds. Named systems like Boehm, Oehler and Albert each embody distinct acoustic strategies that affect tone color, response and intonation.

How do Boehm, Oehler and Albert systems differ in sound and mechanism?

Boehm clarinets use ring keys and relatively large, evenly spaced tone holes for smooth scale and bright, flexible tone. Oehler instruments employ more complex keywork and often smaller holes for a dark, focused sound and fine tuning control. Albert clarinets retain simpler keywork and cross-fingerings, favoring direct resonance and expressive pitch shading.

How can I preserve the original resonance of a historical clarinet?

Preserve original resonance by avoiding reboring or tone-hole enlargement, using reversible materials, and documenting all work. Maintain stable humidity, replace pads with appropriate traditional materials and regulate keys conservatively. For significant instruments, consult a conservator before any intervention that might alter bore or tone-hole geometry.

Can modern adjustments improve resonance without altering historical character?

Yes, many improvements are possible through careful pad seating, key regulation, spring adjustment and choice of mouthpiece and reeds. These changes can enhance sealing and response while leaving the underlying resonance system intact. Any irreversible modifications should be minimal, well documented and guided by historical and acoustic understanding.

Where can I find archival measurements or maker records for specific clarinets (e.g., Martin Freres)?

Archival measurements and maker records may be found in museum collections, university instrument archives, published catalogs and specialized research publications. For Martin Freres and similar makers, surviving workshop documents, trade catalogs and documented instruments in public collections provide valuable data on bore profiles, tone-hole layouts and intended resonance systems.