If you have ever heard a clarinet suddenly sound like a dream teetering on the edge of a nightmare, you have probably met the B whole-tone scale. It is the sound of mystery in a Paris street at midnight, of Debussy's clouds drifting out of tune with gravity, of a jazz soloist bending time over a restless rhythm section.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The B whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is a six-note symmetrical scale built only from whole steps, starting on written B. It gives you floating, dreamlike colors, perfect for Debussy-style impressionism, jazz solos, and modern film music, and it strengthens alternate fingerings and ear training.

The strange magic of the B whole-tone scale

The B whole-tone scale is one of those colors that seems to bend the air around your clarinet. On Bb clarinet, written B as your starting point sends you into a ladder of pure whole steps, no half steps to pull you back to earth. It is like climbing a staircase that never quite reaches a landing.

Claude Debussy loved that sound. Listen to “Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune” or “La Mer” and you will hear whole-tone figures floating through the orchestra, often in the flute, oboe, and clarinet. When a clarinetist in the Orchestre de Paris or the Berlin Philharmonic shapes those phrases, the whole-tone color makes harmony feel weightless, almost like water.

Clarinetists who lived inside the whole-tone sound

The B whole-tone scale might sound modern, but its spirit reaches all the way back to the early clarinet pioneers. Anton Stadler, the friend and muse of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, experimented with unusual scalar patterns on his extended basset clarinet. While Mozart's Clarinet Concerto in A does not use a literal B whole-tone scale, some of the chromatic runs in the Adagio and Rondo hint at the same fluid, sliding color that later composers would expand with pure whole tones.

Heinrich Baermann, idol of Carl Maria von Weber, brought a more theatrical edge. In Weber's Clarinet Concerto No. 1 and the Concertino, the clarinet line sometimes brushes up against whole-tone fragments in rapid arpeggios. Early 19th-century audiences heard these as daring, even exotic colors. For us, they are the doorway to the B whole-tone vocabulary that modern composers seized with both hands.

Fast forward to the 20th century and the names change, but the love of this scale only grows. Sabine Meyer uses whole-tone figures with incredible control in Olivier Messiaen's “Quatuor pour la fin du temps,” especially in the “Abime des oiseaux” movement. When she stretches those intervals and dips into the chalumeau register, you can almost see the harmonies shimmering like stained glass.

Martin Frost often leans into whole-tone ideas in live performances of Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales” and Kalevi Aho's clarinet concerto. You hear rapid, almost acrobatic runs that twist through whole-tone cells, including B whole-tone shapes, to create that modern, unsettled edge. His recording with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra is full of this kind of color.

On the more lyrical side, Richard Stoltzman uses whole-tone fragments in his improvisations on tunes like “Over the Rainbow” and in arrangements of Ravel and Debussy. Even when he is playing a standard melody, you can hear him slip in a quick B whole-tone run as a kind of sparkling ornament.

From Benny Goodman to David Krakauer: the B whole-tone scale in jazz and klezmer

Jazz clarinetists fell in love with the whole-tone scale almost as soon as early swing musicians heard Debussy and Ravel. Benny Goodman used whole-tone licks, including B whole-tone ideas, to create tension before landing back on diatonic material. Listen to his solos on “Sing, Sing, Sing” or “King Porter Stomp” and you can hear short bursts of symmetrical scales that cut across the harmony like a knife.

Artie Shaw pushed that even further. In recordings like “Nightmare” and “Concerto for Clarinet,” you can pick out whole-tone runs that sound like controlled chaos. A B whole-tone fragment over a dominant chord suddenly makes the harmony tilt, then he snaps everything back with a bluesy phrase. That contrast is pure drama.

Buddy DeFranco, stepping into the bebop era, turned the whole-tone scale into a fast, slippery weapon. Over tunes such as “Cherokee” and “What Is This Thing Called Love,” he often outlined altered dominant chords with whole-tone lines. On a written B for the clarinet, the B whole-tone scale lets you hint at sharp 5 and flat 5 colors, which bebop players loved for their bite.

In klezmer, the whole-tone sound arrives more as a passing color than a main flavor, but it is powerful when used. Giora Feidman sometimes bends through whole-tone fragments in pieces like “The Lonely Violinist” arrangements and in his work with the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. It gives a surreal edge to the usually modal klezmer language.

David Krakauer, especially in his projects with Kronos Quartet and Klezmer Madness, treats scales like raw material for storytelling. In more experimental tracks, he leaps through B whole-tone shapes at the top of the clarinet, screaming above the band, then crashes back into the familiar Ahava Rabbah mode. The switch in scale feels like a change in reality itself.

The whole-tone scale has only 6 different notes before it repeats, compared to 7 in a major scale. On Bb clarinet, that compact structure makes patterns easy to memorize and perfect for quick altered dominant runs in jazz and contemporary classical music.

Pieces and recordings where the B whole-tone scale comes alive

The B whole-tone scale shows up more often than you might think, sometimes in the spotlight, sometimes hiding in a transition. Here are some places where clarinetists encounter or echo that sound.

- Debussy: Rhapsodie for Clarinet and Piano – In many performances, including those by Sabine Meyer and Paul Meyer, whole-tone gestures color transitions and cadenzas. Even when not strictly on B, the same pattern you practice in the B whole-tone scale appears under the fingers.

- Ravel: Daphnis et Chloe – Orchestral clarinet parts include sweeping runs and dreamy figures that often outline whole-tone collections. A clarinetist in the London Symphony Orchestra or the Boston Symphony Orchestra will meet these lines regularly.

- Messiaen: Quatuor pour la fin du temps – While Messiaen used his own modes, whole-tone colors sit nearby. The technical and coloristic demands are similar to fluent whole-tone work, especially in the “Abime des oiseaux” clarinet solo.

- Stravinsky: The Soldier's Tale – Short clarinet gestures brush past symmetrical scales and whole-tone fragments, giving a sly, unsettled character to the part.

- Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue – The opening clarinet glissando often hides a quick whole-tone touch as players decorate the rise to that famous high note. Many arrangements include whole-tone flourishes in the inner passages.

Film composers pick up this language too. In scores by John Williams, Alexandre Desplat, and Danny Elfman, clarinet lines in mystery or dream sequences often tip toward whole-tone patterns. You might be asked in a studio to run a quick written B whole-tone slide to underline a magical moment or a plot twist.

On the jazz side, look for recordings like:

- Artie Shaw – Concerto for Clarinet

- Buddy DeFranco – Mr. Clarinet

- Eddie Daniels – Breakthrough

Each of these albums features solos where the clarinetist leans into whole-tone licks, sometimes clearly starting from B, to twist the harmony in unexpected ways.

From impressionism to modern scores: a short history of this scale

The whole-tone scale existed in theory long before clarinetists started practicing it seriously. Early 19th-century theorists played with the idea of a scale built entirely on whole steps, but it felt too unstable for everyday use. The clarinet of that era, with simpler keywork and intonation, was better suited to diatonic and simple chromatic lines.

The real turning point came with French impressionism. Composers like Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel wanted harmony that felt like light on water, shapes without sharp edges. The whole-tone scale delivered exactly that. As clarinets in Paris and Lyon evolved, with more keys and better tuning, players could glide through scales like the B whole-tone with far more security.

By the time Olivier Messiaen and later spectral composers entered the scene, the clarinet was ready. Extended techniques, open fifths, and color trills mixed naturally with whole-tone passages. In the 20th century, Martin Freres instruments played in French conservatories and city bands where students first tasted these sounds in etudes and orchestral excerpts.

Jazz musicians picked up the scale from both classical scores and piano harmonies. Pianists such as Thelonious Monk and Art Tatum loved whole-tone runs over dominant chords. Clarinetists borrowed the same idea, practicing written B whole-tone patterns to use over E7 or F7 chords in swing charts.

Today, the B whole-tone scale lives comfortably in:

- contemporary concertos by composers like John Adams and Esa-Pekka Salonen

- clarinet choir works where inner voices paint hazy harmonies

- game and film music sessions that need instant “mystery” color

How the B whole-tone scale feels under the fingers and in the heart

Emotionally, the B whole-tone scale feels like balancing on a tightrope. There is no true leading tone, no note that begs to resolve. On Bb clarinet, that gives you huge freedom. You float. You tease. You delay the landing as long as you want.

Play it slowly, starting from written B, and let each note ring. It can sound like fog rolling over a harbor at night. Speed it up, and it turns into a cascade of bright sparks, almost like metal scraping against metal. In jazz, it feels daring. In Debussy, it feels like memory. In klezmer-inspired experiments, it feels like a dream inside a dream.

There is another bonus: practicing this scale sharpens your ear. Because the intervals are all whole steps, you cannot lean on familiar tonic-dominant shapes. You have to listen to your tone, your throat position, your register key, your left-hand ring fingers, and your air. It pulls you into a deeper relationship with both mechanics and color.

Why the B whole-tone scale matters for your playing

If you are a student, learning the B whole-tone scale connects you directly to the language of Debussy, Ravel, and modern film scores. It also gives you a secret weapon in jazz band. That scary-looking altered dominant chord on the chart suddenly becomes a playground when your fingers know this scale cold.

For orchestral and chamber players, fluency in B whole-tone patterns makes tricky passages feel much more secure. Instead of reading a mess of accidentals in a Ravel solo, you recognize the pattern: “Oh, that is just a version of my B whole-tone scale.” The brain relaxes, the hand follows.

For improvisers, the scale becomes a color switch. Need more tension over a V7 chord? Reach for your B whole-tone fingering pattern. Need to suggest magic or strangeness in a solo clarinet piece? A slow, singing B whole-tone line will do it immediately.

| Use Case | Why B Whole-Tone Helps | Example Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Orchestral excerpts | Recognize whole-tone patterns in complex passages | Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky |

| Jazz improvisation | Create altered V7 colors over swing or bebop tunes | Benny Goodman style solos |

| Film and game music | Instant “mystery” or “dream” atmosphere | Studio recording sessions |

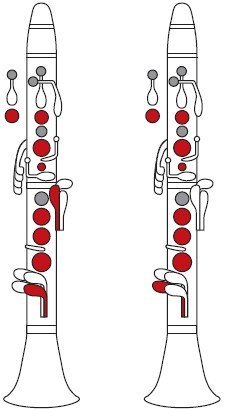

A quick word on fingerings and the free chart

You will see all the details in the free fingering chart, but here is the comforting news: the B whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is mostly made of familiar friends. Starting from written B in the staff, you step through a mixture of standard fingerings and a couple of alternate choices in the throat and clarion registers.

The chart gives you each written pitch, a clear diagram of which keys to press, and suggestions for alternative fingerings that work well in fast passages or soft dynamics. Use it as a visual partner while you listen carefully to your sound and intonation.

- Play the written B whole-tone scale slowly, two octaves if you can, using the chart.

- Repeat in different rhythms: long-short patterns, triplets, and swung eighth notes.

- Improvise a 4-bar phrase using only B whole-tone notes, then resolve to a simple major chord.

| Practice Segment | Time | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Slow scale with tuner | 5 minutes | 3 times per week |

| Articulation patterns on B whole-tone | 5 minutes | 2 times per week |

| Improvised phrases using the scale | 5 minutes | Daily |

Key Takeaways

- The B whole-tone scale connects you to Debussy, Ravel, jazz legends, and modern film scores with a single symmetrical pattern.

- Practicing this scale sharpens your ear, solidifies alternate fingerings, and opens new colors for improvisation and interpretation.

- Use the free fingering chart as a visual guide, then turn the pattern into your own musical stories on Bb clarinet.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet B whole-tone scale fingering?

Bb clarinet B whole-tone scale fingering is the pattern of written notes and key combinations that produces a six-note whole-tone scale starting on written B. You ascend entirely in whole steps, often using a mix of standard and alternate throat and clarion fingerings. It is a core tool for impressionistic and jazz colors.

Why should I practice the B whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet?

Practicing the B whole-tone scale strengthens your ear, supports altered dominant harmony in jazz, and prepares you for whole-tone passages in Debussy, Ravel, and modern scores. It also improves your fluency with alternate fingerings and helps you feel more confident in contemporary chamber and orchestral repertoire.

How often should I include the B whole-tone scale in my routine?

Short, consistent sessions work best. Try 5 to 10 minutes on the B whole-tone scale three or four times per week. Mix slow, tuned practice with faster articulated patterns and free improvisation. Over time, the pattern will feel as natural as a major scale under your fingers.

Is the B whole-tone scale only for advanced clarinet players?

No. Intermediate players can benefit a lot from this scale. The fingerings are familiar, and the symmetrical pattern actually makes memorization easier than some traditional scales. Start slowly with a clear fingering chart, listen carefully to your intonation, and focus on relaxed, singing tone.

Where will I encounter the B whole-tone sound in real music?

You will hear and play this sound in impressionist works by Debussy and Ravel, early 20th-century pieces by Stravinsky and Messiaen, jazz standards with altered dominant chords, and many film or game scores. Once you know the scale, you will start spotting its patterns in solos, accompaniments, and transitions.

For more clarinet inspiration, see other fingering stories and charts across MartinFreres.net, including guides on chromatic flexibility, over-the-break control, and historical playing styles.