If you have ever played a run that felt like the floor disappeared under your feet, you have already met the F whole-tone scale. On Bb clarinet it glows with that dreamy, floating sound you hear in Debussy, Ravel, and smoky late-night jazz solos where the harmony seems to melt and reform in midair.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The F whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is a symmetrical 6-note pattern built entirely from whole steps starting on written F. It creates a dreamy, floating sound used in impressionist music and jazz improvisation, and it helps clarinetists expand color, flexibility, and expressive phrasing.

The magic sound of the F whole-tone scale

Play the F whole-tone scale slowly on your Bb clarinet, from written F just above the staff up to high E, and listen. No half steps. No leading tones tugging you toward a cadence. Just open space. Claude Debussy loved this sound in pieces like “Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune” and “La Mer,” and clarinet parts in those scores often trace fragments that feel just like this pattern.

In those shimmering orchestral textures, clarinet voices from the Orchestre de Paris or the Berlin Philharmonic seem to hang over the strings like mist. Players such as Sabine Meyer and Karl Leister have recorded Debussy and Ravel with a liquid tone where the whole-tone passages almost refuse to land. That is the emotional heart of this scale: it suspends time.

The F whole-tone scale gives you 6 distinct notes before it repeats at the octave. This symmetry helps Bb clarinet players practice even finger motion and smooth air support across throat tones, clarion, and altissimo.

Clarinet voices that lived inside the whole-tone color

The F whole-tone scale might seem like a modern toy, but its spirit has tempted clarinetists for over a century. Think of it as a favorite spice in the kitchen of some very serious players.

In classical and impressionist repertoire, French soloists such as Jacques Lancelot and Guy Deplus painted whole-tone runs in Debussy “Rhapsodie” and Ravel “Daphnis et Chloé” with a gentle brush, using soft throat tones and perfectly focused clarion notes around written F, G, and A. Their recordings with the Orchestre National de France are full of these glassy, sliding colors.

Jump to the 20th century and you find Richard Stoltzman weaving whole-tone fragments into his phrasing in pieces by Olivier Messiaen and Toru Takemitsu. Listen closely to his breathy pianissimo and you can hear how he shapes each interval of the F whole-tone scale as if it were a sung vowel, especially on long B and C# in the upper clarion register.

On the jazz side, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw may be remembered for bright swing, but their ballad solos often flirt with whole-tone shapes. In arrangements of “Body and Soul” or “Stardust,” quick chromatic turns suddenly give way to sequences built on whole steps. Later, Buddy DeFranco turned this into a language of his own, especially in his bebop lines over altered dominant chords where the F whole-tone sound fits perfectly over a G7 or Ab7 harmony.

Modern clarinet explorers push this color even further. David Krakauer and Giora Feidman, kings of klezmer clarinet, drop whole-tone runs as a surprise flavor inside freygish and minor scales, especially in high-energy pieces such as “Der Heyser Bulgar” or “Ale Brider.” Their altissimo shrieks around high C# and D feel like they hover between grief and laughter, and whole-tone fragments often sit right at that emotional tipping point.

From impressionist forests to late-night jazz clubs

The F whole-tone scale might be labeled “modern,” but its journey starts with 19th-century harmony slowly loosening its rules. Composers like Franz Liszt and Alexander Scriabin toyed with whole-tone chords on piano. Clarinetists in orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic and the Leipzig Gewandhaus began to see more chromatic and symmetrical figures in their parts, often brushing close to the whole-tone sound without fully committing.

Debussy then stepped in and treated the whole-tone scale as a color on its own. In orchestral works, he gave clarinet voices phrases that outline whole-tone patterns on written F and G, floating over harp glissandi and muted horns. Suddenly, the Bb clarinet was not just a lyrical storyteller in Mozart and Brahms. It became a painter of light and mist.

Ravel followed suit in scores such as “Boléro” and “Rapsodie espagnole.” Clarinetists like Heinrich Geuser and later Martin Frost showed how elegantly the F whole-tone color can cut through a huge orchestra without sounding harsh, using focused embouchure and very steady diaphragm support.

In jazz, the story continues in smoky clubs instead of concert halls. Early players such as Johnny Dodds and Sidney Bechet on soprano sax opened the door with bold, sliding lines. Their clarinet contemporaries heard that tension and borrowed the idea. By the time Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw were recording with big bands, whole-tone based licks sat neatly inside turnarounds and bridge sections.

Modern jazz clarinetists like Eddie Daniels and Anat Cohen often practice whole-tone scales explicitly, building patterns from F whole-tone to outline altered dominants over tunes such as “All the Things You Are” or “There Will Never Be Another You.” On their recordings you can hear rapid runs from written F up to high E and F#, all in whole steps, darting around the harmony and giving improvisations that dreamy instability.

| Era | How F whole-tone appears | Representative clarinetists |

|---|---|---|

| Late Romantic | Chromatic orchestral runs that hint at whole-tone ideas around F and G | Heinrich Baermann, Richard Mühlfeld |

| Impressionist | Clear whole-tone fragments in Debussy and Ravel clarinet parts | Jacques Lancelot, Sabine Meyer |

| Jazz & swing | Whole-tone based licks over dominant chords in solos | Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Buddy DeFranco |

| Contemporary & film | Atmospheric clarinet lines in soundtracks and new music | Martin Frost, Eddie Daniels, Anat Cohen |

Iconic pieces where the F whole-tone color shines

Once you start listening for it, the F whole-tone sound shows up everywhere. Sometimes it is center stage, sometimes just a hint in a clarinet run or a passing phrase between chalumeau and clarion registers.

In classical and impressionist repertoire, look for it in:

- Debussy “Première Rhapsodie” for clarinet and piano, especially in the cadenza where written F, G, A, B, C# and D# often line up into whole-tone fragments.

- Ravel “Daphnis et Chloé,” where second clarinet sometimes outlines whole-tone figures that blend with flutes and oboes.

- Messiaen “Quatuor pour la fin du temps,” solo clarinet movement played by artists like Jorg Widmann, who stretches intervals and occasionally hints at whole-tone tension.

In jazz and swing, you can hear related flavors in:

- Benny Goodman recordings of “Sing, Sing, Sing” and “King Porter Stomp,” where breaks often flirt with whole-tone shapes over dominant chords.

- Artie Shaw's “Begin the Beguine,” in which the dancing clarinet melody can be ornamented live with whole-tone fills from F whole-tone during turnarounds.

- Buddy DeFranco's bebop interpretations of standards like “How High the Moon,” full of rapid F, G, A, B, C# and D# runs.

Klezmer and folk clarinetists bend this color into their own languages. Giora Feidman often slides between notes that mirror whole-tone gestures in pieces by Naftule Brandwein. David Krakauer uses F whole-tone fragments in his work with the Klezmatics and on albums where clarinet meets electronic textures, creating a surreal, almost cinematic atmosphere.

Film composers love the whole-tone sound. Think of Bernard Herrmann's suspenseful scores or Alexandre Desplat's more recent soundtracks. Clarinet sections in studios like Abbey Road or Sony Pictures often read lines that move in whole steps starting on written F or G, designed to make the audience feel like reality has tilted sideways for a moment.

Why the F whole-tone scale feels so dreamy on Bb clarinet

Emotionally, the F whole-tone scale is like standing on a pier at night, not sure where the water ends and the sky begins. With no half steps, there is no obvious “home.” Your ear drifts. On clarinet, that is incredibly powerful. The instrument's singing upper register and expressive throat tones amplify the ambiguity.

Play the scale as a slow legato line from written F to high E, shaping each note with vibrato or gentle dynamic swells. You might feel it lean toward impressionism on reed and wood, like Debussy on a Buffet R13 or a vintage Martin Freres clarinet. Push it louder and more accented and it suddenly sounds like modern jazz, ready to sit over a G7alt chord or a French chanson with rich accordion harmonies.

For many players, this scale becomes a safe place to experiment. Because every note is a whole step away, you can move freely without worrying about wrong accidentals. That freedom encourages you to focus on air speed, embouchure flexibility, and the color changes between chalumeau, clarion, and altissimo registers.

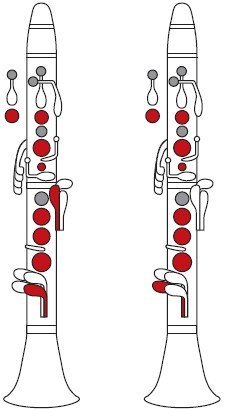

How to let the fingering chart work for you

Your F whole-tone scale fingering chart for Bb clarinet lays out every note you need: F, G, A, B, C#, D#, and back to F. The mechanics are simple, but the voice you give those fingers is what matters. Think of the chart as a map, not the journey itself.

Most of the scale falls in comfortable clarion territory, with standard left-hand index and ring finger combinations. The real art is in the transitions: moving cleanly from throat A to B, or from C# to D# using the side keys without bumpiness. Use the chart to confirm which left-hand pinky and right-hand side keys work best for your instrument and reed setup, then let your ear guide your phrasing.

Simple step-by-step way to taste the F whole-tone scale

- Play long tones on written F, then add G and A, all slurred, focusing on a steady column of air.

- Add B and C#, paying attention to smooth finger motion between throat and clarion notes.

- Include D# and the top F, then descend, keeping your embouchure relaxed on every interval.

- Try the full scale in different dynamics: whisper-soft piano, then a confident mezzo-forte.

Practice ideas: from scale to musical story

You can turn the F whole-tone scale into a short daily ritual that connects you to the same colors used by Sabine Meyer, Benny Goodman, and Giora Feidman. A few focused minutes can change how you hear and shape lines in Mozart, Weber, or your favorite jazz standard.

| Routine | Time | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Slow legato F whole-tone | 3 minutes | Breath support from low F to high E, even finger motion |

| Rhythmic patterns | 4 minutes | Triplets, swing eighths, accents on every other note |

| Mini improv | 3 minutes | Short melodies using only F whole-tone, exploring dynamics |

Try pairing this with other material on MartinFreres.net, such as long tone studies, chalumeau register warmups, and articulation drills in clarion. When you blend the F whole-tone scale with those basics, your everyday practice starts to feel a lot closer to actual music than to simple exercises.

Quick reference: common F whole-tone patterns

- 3-note cells: F – G – A, G – A – B, A – B – C#

- 4-note cells: F – G – A – B, G – A – B – C#, A – B – C# – D#

- Arpeggio feel: F – A – C#, G – B – D#, A – C# – F

Why this scale matters for you, right now

Mastering the F whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is not about collecting one more technical skill. It is about giving yourself another emotional color. If you play Mozart, you will feel your legato improve and your throat tone transitions into clarion become silkier. If you love jazz, your dominant chords will suddenly have a new flavor to taste.

For students, working through this scale with the fingering chart builds confidence in side keys and pinkies, so Weber concertos and orchestral excerpts feel less scary. For professionals, it becomes a way to refresh your ear and keep your improvisation or interpretation from falling into familiar ruts.

Some players even use the F whole-tone scale as a quick sound check. Play it once in the practice room and you instantly hear if your reed, ligature, and barrel combination is responding evenly across the registers. If the C# or D# feels stuffy, you know where to adjust your embouchure or air.

Key Takeaways

- The F whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet offers a floating, impressionistic color heard in Debussy, Ravel, jazz, and film scores.

- Using the fingering chart, you can practice smooth transitions across throat tones, clarion, and altissimo in just a few minutes a day.

- Great clarinetists across genres use this sound to add tension, mystery, and emotional depth to their lines.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the F whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet?

The F whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is a 6-note scale built entirely on whole steps, starting from written F. The notes are F, G, A, B, C#, and D#, then F again. It creates a floating, unresolved color heard in impressionist music, jazz, and many film scores.

Why should I practice the F whole-tone scale?

Practicing the F whole-tone scale improves finger coordination on side keys, throat tones, and pinky keys. It also trains your ear to hear more adventurous harmonies, which helps in jazz improvisation, contemporary music, and expressive phrasing in classical works by Debussy, Ravel, and Messiaen.

How often should I include the F whole-tone scale in my routine?

Many clarinetists use the F whole-tone scale for about 5 to 10 minutes, three or four times a week. A short session of slow legato, rhythmic patterns, and a bit of improvisation is enough to keep the fingerings comfortable and the sound fresh without taking over your practice.

Does the F whole-tone scale help with jazz improvisation?

Yes. Jazz clarinetists often use F whole-tone over dominant chords related to G7 or Ab7. The pattern outlines altered tensions and gives solos a modern, slightly unstable color. Practicing this scale helps you hear and play those sounds confidently in tunes and solos.

Can beginners learn the F whole-tone scale, or is it only for advanced players?

Beginners can absolutely learn the F whole-tone scale. The fingerings are mostly familiar, and the symmetrical pattern is easy to memorize. Starting with slow, slurred practice and using a clear fingering chart helps students build control and confidence while enjoying a new sound early on.