If the major scale is bright midday sun, the G Locrian scale on Bb clarinet is that strange violet glow just before night takes over. It feels unstable, a little dangerous, and completely addictive once your ear learns to love its shadows.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The G Locrian scale on Bb clarinet is a 7-note mode built from A b-flat major starting on G. It uses G, A-flat, B-flat, C, D-flat, E-flat, and F, and it trains your ear for dark, tense colors that expand your improvisation and phrasing.

The strange, beautiful mood of the G Locrian scale

On Bb clarinet, the G Locrian scale feels like walking on a rope bridge. Every step matters. That half-step between G and A-flat, and the uneasy pull from D-flat to E-flat, makes your fingers and your ear listen harder than they usually do in a simple G major run.

This mode is the seventh mode of A b-flat major, but most clarinetists first meet it not as theory, but as a color: the haunted chord at the bottom of a film score, the strange tension in a jazz solo, the whispered line in a contemporary clarinet piece that never quite settles. G Locrian is the sound of questions that never quite get answered.

The G Locrian scale has 7 notes with 5 semitone steps between them, more half-steps than a regular major scale. This tight spacing gives clarinetists those gritty, close-interval colors that composers love for suspense and mystery.

Clarinetists who thrived in Locrian shadows

Classical clarinetists rarely see a scale labeled “G Locrian” in their parts, but they meet its sound constantly in orchestral writing and chamber music. Anton Stadler, Mozart's friend and clarinet muse, played lines that skirted Locrian territory in the darker stretches of the Clarinet Concerto in A and the Clarinet Quintet in A. Those low-register phrases that lean on B natural over a C bass line flirt with the Locrian flavor long before anyone named it out loud.

Heinrich Baermann, the great romantic clarinetist who inspired Carl Maria von Weber, tackled concertos full of unstable diminished harmonies. In Weber's Clarinet Concerto No. 1 and the Concertino, Baermann would have lived inside passages that hint at Locrian color: diminished chords, flattened fifths, and wandering inner voices in the chalumeau register.

Move forward more than a century and you hear the same ghosts in Sabine Meyer's recordings of 20th century works. Listen to her work on Luciano Berio's “Sequenza IXa” or Karlheinz Stockhausen's “In Freundschaft”. While the pages do not shout “G Locrian scale” in big letters, she shapes long lines where G is held against harmonies that drag it into Locrian territory, especially when a low clarinet or bass clarinet supplies a clashing bass note.

Martin Frost often walks right up to that Locrian edge in pieces like Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales”. In some of the more theatrical, suspended moments, the clarinet floats over a pedal bass that turns ordinary scale fragments into unstable modes. Play those same lines in your practice room as a G Locrian pattern and you suddenly hear how modern composers think about tension on the instrument.

On the jazz side, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw did not usually name modes, but you can hear Locrian coloring in their treatment of half-diminished chords. In recordings of “Stompin' at the Savoy” or “Begin the Beguine”, listen for those quick runs over ii half-diminished chords in minor keys. Transpose one of those licks to start on G over an A b-flat major backing and you will recognize the G Locrian layout in their fingers.

Buddy DeFranco, who loved modern harmony, pushed even deeper into this sound. On albums like “Mr. Clarinet” he darts through ii-v-i chains where the ii chord is half-diminished. Any lick he plays there can be re-heard as a Locrian phrase. The same is true for Eddie Daniels in his more fusion-influenced solos, where altered and Locrian ideas blur together in blazing passages across the break.

Klezmer clarinetists like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer reach similar flavors walking around the “Freygish” and altered minor scales. In some slow doinas or improvisations on traditional tunes, they land on flattened fifths and dark leading tones that feel like cousins of G Locrian, particularly when the tonic is unstable and the clarinet wails in the throat tones.

Pieces and recordings where G Locrian colors shine

You may never see “G Locrian” printed in a clarinet part, yet the sound hides in many scores. In Igor Stravinsky's “The Rite of Spring” and “Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo”, clarinet lines twist through diminished and quartal harmonies that share Locrian DNA. Practice a G Locrian scale, then listen again to how those clarinet jumps feel familiar in your hands.

Dmitri Shostakovich loved dissonant woodwind writing. In his Symphony No. 5 and Symphony No. 10, clarinet parts sometimes cling to a pitch like G while the orchestra shifts underneath. In those moments, the scale around that note can feel Locrian, especially when low brass and double basses move through diminished sonorities.

Contemporary concert works for clarinet explore this tension openly. Try playing patterns from G Locrian before practicing Pierre Boulez's “Domaines” or Jorg Widmann's “Fantasie”. The flattened fifth and rich half-step clusters in your scale work will suddenly echo what you see on the page.

On the jazz side, listen to John Coltrane's “Impressions” or “Countdown” and then look for clarinet interpretations by players like Anat Cohen or Eddie Daniels. Whenever they fly over a minor ii half-diminished to V7 change, a Locrian flavor appears. Transpose those lines onto G on your Bb clarinet and you will literally be playing G Locrian ideas, just in a different harmonic context.

Film scores are full of quiet Locrian ghosts. Think of clarinet in suspenseful passages by composers like John Williams or Alexandre Desplat. In darker cues of scores like “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” or “The Shape of Water”, clarinet parts often sit on the edge of tonality, tracing lines that could easily be mapped onto G Locrian if you changed the bass note.

For chamber music fans, the slow, mysterious sections of Olivier Messiaen's “Quartet for the End of Time” have clarinet lines that flirt with Locrian color between C, F, and G centers. Practice your G Locrian scale, then play those excerpts and notice how the flattened fifth and minor second feelings give them their floating, timeless character.

From medieval church modes to modern clarinet solos

The Locrian mode has old roots. In medieval church theory it was the odd child of the modal family, the mode that felt too unstable to use as a home base. That built-in instability came from its diminished fifth, the interval between the first and fifth notes of the scale. On G Locrian, that is the span from G to D-flat.

For early wind players, including the ancestors of the modern clarinet like the chalumeau, such an interval was more a color than a full tonal center. Composers leaned on it to create tension, not to rest. As the Baroque period bloomed, players who would later inspire clarinet design were already decorating diminished chords with turns and mordents very similar to G Locrian fragment patterns.

By the Classical and Romantic eras, the clarinet had gained keys and improved tuning. Composers like Mozart, Weber, and Brahms put more and more half-diminished chords into their harmonic language. Even if they did not write “play G Locrian here” over the staff, that is exactly the scale shape implied when a clarinetist solos over a ii half-diminished chord in A b-flat major or related keys.

The 20th century changed how musicians thought about modes. Jazz theory named Locrian explicitly, especially for half-diminished chords. Classical composers, from Debussy to Messiaen, wrote modal lines that floated free from typical major-minor thinking. Suddenly the G Locrian scale was more than a passing color; it became a training tool for improvisers, composers, and adventurous clarinetists.

Today, advanced clarinet students who study contemporary repertoire or modern jazz quickly meet the G Locrian scale. Teachers use it to stretch the ear, to break out of major scale habits, and to prepare players for pieces where the clarinet must sit confidently on top of dissonant harmonies without losing focus or pitch.

How the G Locrian scale feels under clarinet fingers

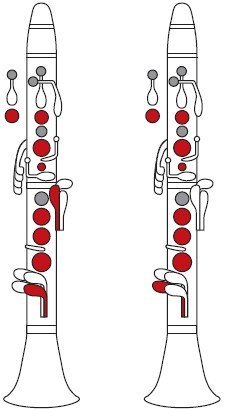

On Bb clarinet, the written G Locrian scale (spelled as G, A-flat, B-flat, C, D-flat, E-flat, F, G) lives comfortably from low chalumeau up through the clarion register. Because so many notes are b-flats and flats, your left-hand index and right-hand index fingers stay busy, and the cross-fingerings create that slightly gritty resistance that matches the sound of the mode.

The free clarinet fingering chart on this page shows each note with clear diagrams, so you can relax into the feel of the pattern instead of worrying about remembering exact key combinations. Once the fingerings are automatic, you can focus on shaping the color: exaggerating soft attacks in the chalumeau register, or adding a touch of vibrato in the clarion register to make the Locrian tension shimmer.

| Pattern | Feeling under fingers | Best use |

|---|---|---|

| Straight G Locrian (one octave) | Compact, many flats, steady left-hand index work | Warm-up, ear training, tone control in chalumeau |

| Broken 3rds in G Locrian | Quick alternation across the break if extended | Building control for contemporary solos and jazz fills |

| Arpeggio focus (1-b3-b5-b7) | Targeted work on diminished shapes | Improvising over half-diminished chords |

Why the G Locrian sound matters to your musical heart

The emotional pull of the G Locrian scale is simple: it refuses to settle. Play G major and your ear smiles by the third note. Play G Locrian and your ear leans forward, waiting for some kind of rescue that never quite comes. That is what makes it such a powerful storytelling tool on clarinet.

In the low chalumeau register, a soft G Locrian line feels like a secret. The B-flat and D-flat brush against the natural resonance of the instrument, creating gentle friction. Up in the clarion register, especially around written C and D-flat, the scale starts to sound icy and exposed, perfect for film-style suspense or modern chamber whispers.

Practicing this scale teaches patience in phrasing. Instead of rushing to a bright resolution, you learn to savor suspended notes, to milk a long F held over an implied G bass, or to shape a crescendo over G to D-flat that never truly relaxes. That control pays off everywhere, from Mozart to Messiaen.

What mastering G Locrian opens up for you

Grabbing the G Locrian scale fluently on Bb clarinet is like adding a new color to your paint box. Technically, it helps you deal with half-diminished chords, tricky accidentals, and fast passages full of flats. Artistically, it trains you to love dissonance instead of shying away from it.

If you are working on classical pieces, this comfort with Locrian color makes Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and even late Brahms passages feel less scary. In jazz or klezmer settings, it lets you solo with confidence over minor progressions where the piano or accordion hints at half-diminished harmony. In contemporary solo works, where the composer might leave you holding an exposed G against a strange electronic or piano texture, your G Locrian practice keeps your pitch and tone calm.

On a personal level, this scale encourages bravery. You learn to stand on notes that sound “wrong” in isolation and make them feel intentional through dynamics, vibrato, and articulation. That kind of bravery spills over into everything else you play.

Simple G Locrian practice ideas with your fingering chart

The fingering chart gives you the map, but how do you let this scale sink into your playing in a musical way? Here are a few practice structures that feel more like improvisation than homework.

- Play the G Locrian scale slowly in long tones, 4 beats per note, from low G up one octave and back down. Focus on even air support and a relaxed embouchure.

- Next, play the same scale in slurred pairs (G-A-flat, A-flat-B-flat, etc.), using a gentle crescendo across each two-note group.

- Improvise a 4-bar “movie cue” in G Locrian: pretend you are underscoring a suspense scene, only using the notes of the scale.

- Transpose one of your favorite G minor licks so that the notes fit the G Locrian pattern, then compare the mood.

| Routine | Time | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Long-tone G Locrian (1 octave) | 5 minutes | 3 times per week |

| Broken 3rds & arpeggio focus | 7 minutes | 2 times per week |

| Free Locrian improvisation | 5 minutes | Daily warm-down |

Key Takeaways

- The G Locrian scale on Bb clarinet trains your ear and fingers to love dissonance and tension.

- You already meet its sound in classical, jazz, klezmer, and film music, even if it is not labeled.

- Use the fingering chart to free your technique, then turn G Locrian into a storytelling tool in your own playing.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet G Locrian scale fingering?

The Bb clarinet G Locrian scale fingering is the pattern you use to play G, A-flat, B-flat, C, D-flat, E-flat, and F in order on your clarinet. It combines standard chalumeau and clarion fingerings, with several flats that keep your left-hand and right-hand index fingers active.

Why should clarinetists practice the G Locrian scale?

Practicing the G Locrian scale builds control over half-diminished harmony, improves intonation in dissonant passages, and strengthens fluency with flat-heavy fingerings. It also prepares you for modern repertoire and jazz situations where tension and unresolved color are part of the musical story.

How is G Locrian different from G minor on Bb clarinet?

G natural minor uses G, A, B-flat, C, D, E-flat, and F, while G Locrian uses G, A-flat, B-flat, C, D-flat, E-flat, and F. The Locrian scale lowers the 2nd and 5th degrees, creating a diminished fifth between G and D-flat, which gives the scale its unstable and darker sound.

Where will I encounter G Locrian in clarinet music?

You will hear G Locrian colors in passages built on half-diminished chords, especially in jazz, film scores, and contemporary classical works. Clarinet parts by composers like Shostakovich, Messiaen, and modern jazz writers often imply Locrian patterns without naming the mode directly.

How long should I spend on G Locrian in my practice routine?

About 10 to 15 minutes per session is enough for most players. Use a mix of long tones, scale runs, and short improvisations. Regular, relaxed work a few times each week is better than a single long session, and it lets the sound and finger patterns settle naturally.

For more inspiration on tone and scales, you may also enjoy articles on other clarinet scale charts and historical Martin Freres clarinets available across the site.