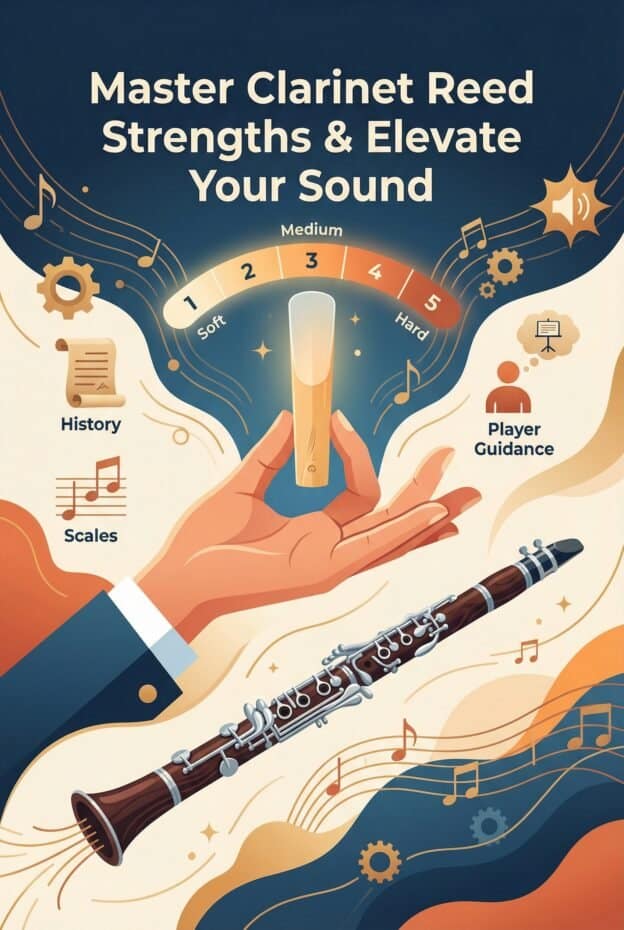

Clarinet reed strength systems are numeric or descriptive scales used to indicate the stiffness of a reed. Historically this evolved from subjective “soft/hard” judgments to mid-20th century numbered scales; today strengths vary slightly by manufacturer, so players compare brands and test reeds by play-testing, tip response and measured thickness to find a dependable match.

Why Reed Strength Matters for Clarinetists

Reed strength directly shapes response, tone color, dynamic range and endurance. A reed that is too soft can feel unstable, pitchy and bright, while one that is too hard can feel resistant, flat and tiring. For advanced clarinetists and technicians, understanding strength systems is important for consistent setups across mouthpieces, ensembles and styles.

Strength interacts with mouthpiece facing length, tip opening and clarinet bore. The same nominal strength behaves differently on a close classical mouthpiece compared with an open jazz design. Knowing how to interpret reed strength markings lets you predict this interaction, reduce trial-and-error, and maintain predictable performance in orchestral, chamber and jazz contexts.

What Are Clarinet Reed Strength Systems?

Clarinet reed strength systems are schemes used by manufacturers to describe how stiff or resistant a reed feels. Most modern systems use numbers, often from 1 (soft) to 5 (hard), sometimes with half or quarter steps. Others use descriptive labels such as soft, medium, and hard, or proprietary categories.

Strength reflects several physical properties: cane density, thickness at the tip, heart and back, and the exact vamp profile. A “3” from one brand can feel like a “2.5” or “3.5” from another because each company calibrates its scale to its own cut, cane source and design goals, not to a universal standard.

Reed strength systems also extend to synthetic materials. Makers of polymer or composite reeds often reference equivalent cane strengths, but the feel can differ because synthetic materials flex and recover differently. Understanding the concept of strength across materials helps players translate between cane and synthetic options.

A Brief History of Reed Strength Systems

For much of clarinet history, players selected reeds by feel and sound, not by printed strength. Before industrial standardization, reeds were often handmade or roughly finished, and clarinetists scraped, clipped and adjusted them to taste. Descriptions such as “soft” or “stiff” were personal, not standardized.

By the late 19th century, as companies like Vandoren in France and American makers expanded production, catalogues began to mention reed “qualities” and occasional gradations. Numeric systems started to appear in the early 20th century, but they were not yet universal. Some firms used 1-3 scales, others used letters or descriptive terms.

After World War II, large-scale manufacturing and global trade pushed makers toward clearer labeling. By the 1950s and 1960s, numbered strength scales from 1 to 5 (with half strengths) became common in Europe and North America. Late 20th and early 21st century innovations, including filed vs unfiled cuts and synthetic reeds, layered new proprietary systems on top of this numeric tradition.

Pre-Industrial Testing and Early Player Techniques

Before industrial reed grading, clarinetists relied on tactile and auditory tests. Players flexed the reed gently between thumb and forefinger, listened for a crisp snap when released, and visually inspected cane fibers. They often selected blanks slightly harder than needed, then scraped and thinned the vamp to taste.

Early 19th century methods described in French and German pedagogical texts mention soaking reeds, then testing long tones and articulation at soft dynamics. Strength was judged by how easily the reed responded in the chalumeau register and whether high notes spoke without biting. The language was qualitative: “souple” (supple), “résistant” (resistant), or “dur” (hard).

Instrument makers and repairers sometimes kept boxes of reeds sorted by their own internal sense of hardness. A player might ask for “the firmer ones” for outdoor work or “the easy ones” for delicate chamber music. Without printed numbers, consistency depended on the ear and experience of individual artisans and performers.

Industrialization, Grading and the Rise of Numbered Scales

Industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries transformed reed production. Companies introduced mechanical cutting machines and more controlled drying processes. This allowed batches of reeds with similar thickness profiles, which made systematic grading possible. Trade journals from the 1890s already mention “selected” and “extra fine” qualities.

By the early 1900s, several European and American manufacturers offered at least two or three hardness levels. Some used letters (A, B, C), others used terms like soft, medium and hard. As clarinet design standardized around the Boehm system, demand grew for predictable reeds that could be ordered by mail with confidence.

From Martin Freres archival catalog notes of the early 20th century, we see references to “choix pour artistes” and graded reed assortments intended for export. While not yet using the modern 1-5 numeric scale, these records show an early move toward systematic hardness categories aligned with professional expectations.

Mid-20th century catalogues from major brands document the shift to numeric scales. A typical scheme ran from 1 to 5, with 2.5 and 3.5 added as intermediate options. By the 1970s, quarter strengths appeared in some lines, reflecting both tighter manufacturing tolerances and player demand for finer control.

| Period | Typical Grading Practice | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1850 | No printed strength | Hand selection, scraping by players |

| 1850-1900 | Qualitative labels | Soft/medium/hard, artisan sorting |

| 1900-1950 | Early numeric & letter codes | 1-3 scales, A/B/C, export assortments |

| 1950-2000 | Standard 1-5 scales | Half strengths, brand-specific calibrations |

| 2000-present | Refined & proprietary systems | Quarter strengths, synthetic equivalences |

Comparing Modern Reed Strength Scales Across Brands

Modern reed strength systems look similar on the box, but they are not interchangeable. A 3.0 from one manufacturer can feel closer to a 2.5 or 3.5 from another because each company defines strength using its own cane, cut and measurement protocols. Players must treat numbers as brand-relative, not absolute.

Most French-cut cane reeds use a 1.5 to 5.0 scale with half steps. American-style cuts and specialty jazz reeds may run slightly softer at the same printed number. Synthetic reed makers often publish comparison charts, but these are approximations. Experienced clarinetists often keep a personal cross-reference chart based on their own play-testing.

Below is a generalized comparison that many players report when using a medium-close classical mouthpiece. It is not a universal standard, but it illustrates typical relationships:

| Brand A (French cut) | Brand B (French cut) | Brand C (jazz cut) | Approx. Feel |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.0 | Soft-medium |

| 3.0 | 2.5+ | 3.5 | Medium |

| 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.5+ | Medium-hard |

For technicians and educators, the key is to ask: “What strength and brand are you using, on which mouthpiece?” When changing brands, advise players to move by half-strength increments and test several reeds before deciding. Documenting these adjustments in a practice journal helps build a reliable personal conversion chart.

Materials & Innovations: Cane vs Synthetic Reeds

Traditional clarinet reeds use Arundo donax cane. Strength depends on fiber density, growth conditions and how the blank is cut. Harder cane with dense fibers yields a stiffer reed at the same thickness. Makers adjust the tip, heart and back to hit target strengths, but natural variability remains, which is why boxes contain both “gems” and rejects.

Synthetic reeds, made from polymers or composites, aim for consistency. Their strength systems often mirror cane numbers, but the feel can differ. Synthetics may have a quicker response and a slightly different resistance curve as you blow harder. Some players find a synthetic labeled “3.0” feels like a cane 2.5 at soft dynamics but closer to 3.0 at forte.

From an anatomy perspective, both cane and synthetic reeds share key zones: the tip (often 0.08-0.12 mm thick), the heart (thickest central area), and the back or heel. A typical progression for cane on a medium mouthpiece might look like this:

- Strength 2.0: tip around 0.08-0.09 mm, relatively thin heart

- Strength 3.0: tip around 0.10-0.11 mm, fuller heart

- Strength 4.0: tip around 0.11-0.12 mm, very solid heart

These values vary by brand, but they illustrate how small thickness changes alter strength. Synthetic reeds often use different internal structures, so the same tip thickness can feel stiffer or more flexible. When mapping synthetic to cane, treat the printed equivalence as a starting point and adjust by feel.

How to Test, Select and Break-In Reeds (maintenance_steps & troubleshooting)

Selecting reeds starts before you play. Begin with visual inspection: look for straight grain, no dark spots, and a symmetrical cut. Check that the tip is even across both rails. Discard reeds with obvious warps or cracks. For synthetic reeds, inspect the tip edge for chips and ensure the table is flat.

Next, perform a gentle finger flex test. Hold the reed by the heel and lightly press the tip against your thumb. It should flex and spring back without feeling mushy or rigid. Compare several reeds of the same box; set aside those that feel extremely soft or hard relative to the group.

Before full playing, briefly soak cane reeds in clean water for 1-2 minutes, not longer. Synthetic reeds usually need only a quick wetting. Mount the reed carefully, aligning the tip just below or flush with the mouthpiece tip. Use a stable ligature tension: firm enough to prevent slipping, not so tight that it chokes vibration.

For break-in, limit initial sessions to 5-10 minutes per reed over several days. Start with mid-dynamic long tones in the chalumeau register, then add simple scales and light articulation. Avoid fortissimo and extreme altissimo on day one. Rotate 3-6 reeds so no single reed is overworked early in its life.

Store reeds in a ventilated case that keeps them flat. Humidity control packs around 45-60 percent relative humidity help stabilize cane and reduce warping. Replace reeds that show deep discoloration, cracks at the tip, persistent waterlogging, or that require noticeably more effort for the same dynamic and pitch control.

Practical Tips: Matching Reed Strength to Player Outcomes

Matching reed strength to your setup and goals starts with an honest look at embouchure, air support and mouthpiece. A beginner on a medium-close classical mouthpiece often plays best around 2.0 to 2.5. This allows easy response and endurance while embouchure muscles develop, without forcing biting to control a too-soft reed.

Conservatory students and orchestral clarinetists typically settle between 2.5 and 3.5 on standard cane reeds. A slightly harder reed (3.0-3.5) on a balanced mouthpiece can improve pitch stability, core to the sound and dynamic range, provided the player has solid air support. For delicate chamber work, some choose a half-strength softer for flexibility.

Jazz and klezmer clarinetists often use more open mouthpieces. Many prefer slightly softer reeds (2.0-3.0) for bends, scoops and fast articulation. Lead players seeking projection in loud bands may move up a half strength or choose a brighter cut while keeping the same nominal number. The key is to test at performance volume, not just in soft practice.

Technicians and repairers should consider reed strength when diagnosing issues. A player complaining of fatigue and flat pitch on a medium mouthpiece with a 3.5 reed may benefit from a 3.0 or a different brand with a more flexible tip. Documenting these changes and their effects on tone and endurance helps refine future recommendations.

Example strength ranges by archetype

- Beginner on medium-close student mouthpiece: cane 2.0-2.5

- Advanced classical on professional medium mouthpiece: cane 2.5-3.5, synthetic equivalent

- Orchestral principal with strong air support: cane 3.0-3.5, occasionally 3.5+

- Jazz lead on open mouthpiece: cane 2.5-3.0, possibly softer for extreme flexibility

Archival Data, Patents and Notable Historical References

Historical records shed light on how reed strength systems evolved. Late 19th century European catalogs mention graded reeds for export, often using terms like “fort” and “faible” rather than numbers. Early 20th century American trade publications describe “assorted hardness” boxes for band and orchestra use.

Mid-20th century patents document mechanical reed profiling machines capable of producing consistent tip and heart thickness. These inventions made modern numeric grading possible by reducing variation within a batch. Some patents specify target thickness ranges for different hardness categories, reflecting a growing scientific approach to reed design.

Archival pedagogical texts from Paris, Leipzig and New York conservatories reference preferred reed “hardness” for orchestral work, often recommending firmer reeds for symphonic repertoire and slightly softer ones for solo literature. These sources confirm that even before universal numbering, players consciously matched reed resistance to musical context.

For historians and collectors, examining original reed boxes, catalog reprints and workshop notes provides valuable insight. Labels, handwritten annotations and early strength markings reveal how individual makers and players navigated the shift from subjective descriptors to the structured clarinet reed strength systems used today.

Key Takeaways

- Clarinet reed strength systems are brand-relative scales that describe stiffness, not universal measurements, so numbers must be interpreted in context.

- History shows a gradual shift from subjective soft/hard judgments to numeric scales enabled by industrial profiling and global trade.

- Effective reed choice depends on matching strength to mouthpiece, material, style and player physiology, then testing and rotating reeds systematically.

FAQ

What is clarinet reed strength systems?

Clarinet reed strength systems are numeric or descriptive scales that indicate how stiff a reed is. Most modern systems use numbers from about 1 (soft) to 5 (hard), sometimes with half or quarter strengths, but each manufacturer calibrates its own scale based on cane, cut and design.

How do reed strength numbers compare between manufacturers?

Reed strength numbers do not compare exactly between manufacturers. A 3.0 in one brand can feel like a 2.5 or 3.5 in another because each company uses its own thickness profiles and cane density. When switching brands, start by adjusting about half a strength and test several reeds to find an equivalent feel.

How were reed strengths determined historically?

Historically, reed strengths were judged by feel and sound rather than printed numbers. Players flexed reeds by hand, inspected cane fibers and tested response on the instrument. Early makers sometimes sorted reeds into soft, medium and hard groups, but standardized numeric scales only became common in the mid-20th century.

Can synthetic reeds be compared directly to cane strengths?

Synthetic reeds often list an equivalent cane strength, but the feel is not always identical. Synthetic materials flex and respond differently, so a synthetic labeled 3.0 may feel slightly softer or harder than a cane 3.0. Use the printed number as a starting point, then adjust by half-strength steps based on play-testing.

How should I choose a reed strength for my mouthpiece and playing style?

Choose reed strength by considering mouthpiece opening, embouchure and musical style. On a medium-close classical mouthpiece, many players start around 2.5-3.0 and adjust for comfort, tone and pitch stability. More open jazz mouthpieces often pair with slightly softer reeds. Test several strengths and brands to find a setup that balances response and control.

What are quick troubleshooting steps when a new reed doesn't feel right?

If a new reed feels wrong, first confirm alignment and ligature tension. If it is too hard, try moving the reed slightly higher on the mouthpiece or testing a half-strength softer. If it is too soft or unstable, move it slightly lower or try a harder reed. Always compare with a known good reed to rule out mouthpiece or embouchure issues.