If the major scale is daylight, the E whole-tone scale is twilight: soft around the edges, a little mysterious, and full of colors that do not quite exist in ordinary life. On the Bb clarinet, that sound has an almost liquid shimmer, the kind you hear in Debussy, Ravel, and the wildest pages of Messiaen. This free clarinet fingering chart for the E whole-tone scale is really an invitation into that dreamy world.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The E whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is a 6-note symmetrical scale built from E with only whole steps. It uses notes E, F#, G#, A#, C, and D. Practicing this scale improves fluid finger movement, modern phrasing, and control of color changes in jazz, classical, and film music.

The sound and story of the E whole-tone scale

Play an E whole-tone scale on your clarinet and you instantly leave normal gravity. No half steps, no usual tension and release, just one floating color that keeps changing shape. That is why composers like Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel loved the whole-tone palette, and why clarinetists from Benny Goodman to Martin Frost still reach for it when they want time to feel a little unreal.

On a Bb clarinet, the E whole-tone scale (concert D whole-tone) sits in a sweet spot. It sings in the chalumeau register, glows in the clarion, and becomes almost vocal in the altissimo. Every note is two semitones away from the next, which gives you that unmistakable, drifting sound you hear in Debussy's “Prelude a l'apres-midi d'un faune” and in so many modern film scores.

Clarinetists who turned the whole-tone sound into magic

The E whole-tone scale is not something players talk about as often as, say, G major. But listen closely and you will hear it all over recorded clarinet history, especially among players who loved color more than straight lines.

In classical repertoire, Sabine Meyer often shapes whole-tone runs in Ravel and Debussy with such smooth finger transitions that you barely notice the technical difficulty. Her recording of Debussy's “Premiere Rhapsodie” with the Berlin Philharmonic hides tiny whole-tone fragments that flash by like light on water. Martin Frost takes the same idea further in contemporary concertos, especially in works by Anders Hillborg and Kalevi Aho, where whole-tone cells explode into full-blown altissimo cascades.

Go back earlier and you can almost imagine Anton Stadler, Mozart's clarinet muse, experimenting with symmetric scales on his extended basset clarinet, even if the term “whole-tone” was not yet part of the daily vocabulary. Heinrich Baermann, Weber's legendary clarinetist, had the kind of liquid technique that would have loved these smooth, evenly spaced notes, especially in improvisatory cadenzas.

In the 20th century, Richard Stoltzman brought whole-tone flavors into his freer interpretations of Bernstein and Copland. Listen to him in Bernstein's “Prelude, Fugue and Riffs” and you will catch that slippery, jazzy color that comes from sequences built on whole steps. The clarinet line bends between blues and whole-tone worlds, almost like a tightrope between Benny Goodman and Debussy.

Speaking of Benny Goodman, whole-tone patterns show up constantly in his big band solos with the Benny Goodman Orchestra. In tunes like “Sing, Sing, Sing” and “Stompin' at the Savoy,” he leans into chromatic and whole-tone-inspired runs that slide across the horn. Buddy DeFranco took that even further in bebop, turning symmetrical scales into high-speed language, especially on recordings with Art Blakey and the Oscar Peterson Trio.

Klezmer innovators like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer sometimes dip into whole-tone gestures when they stretch a traditional freygish scale into something more surreal. That moment when the clarinet cries, then suddenly floats upward in unexpected steps, often brushes right against E whole-tone patterns, especially at the top of the instrument where flavor beats theory.

Iconic pieces and recordings that whisper this scale

The E whole-tone scale rarely shows up as “Play this scale now” in the score. Instead, composers hide it inside arpeggios, flourishes, and short motives. Once you start listening for that equal-step shimmer, you hear it everywhere.

In orchestral and symphonic music, the clarinet often rides whole-tone waves in:

- Debussy's “La Mer” and “Jeux” where clarinets and flutes blend in rippling whole-tone lines.

- Ravel's “Daphnis et Chloe” and “Rhapsodie Espagnole,” especially in the swirling woodwind textures.

- Igor Stravinsky's “The Firebird” and “Petrushka,” where clarinet and bass clarinet jump through otherworldly runs that sit right on whole-tone shapes.

Modern clarinet concertos lean into this color even more. In Henri Tomasi's “Concerto for Clarinet,” symmetric scales in E and F whole-tone frame the most dreamlike passages. John Corigliano's “Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra” features wild altissimo bursts that often pass through whole-tone segments before resolving to diatonic pitches. Performers like Sabine Meyer, Martin Frost, and Kari Kriikku bring out these colors with exaggerated dynamic swells, making the whole-tone patterns feel like moving clouds.

In chamber music, the E whole-tone scale makes guest appearances in:

- Messiaen's “Quartet for the End of Time,” where the clarinet often outlines symmetrical patterns around E and F.

- Debussy's “Premiere Rhapsodie,” especially in the cadenza-like passages with blurred tonal centers.

- Olivier Messiaen's “Theme and Variations” for violin and piano, where clarinetists in arrangements mirror the whole-tone language of the original.

Jazz clarinetists have a love affair with this sound. In Artie Shaw's wildly inventive solos, you can hear whole-tone flashes when he leans into dominant chords with altered tensions. Buddy DeFranco used them over V7#5 chords, and modern players like Anat Cohen and Ken Peplowski sometimes shade their lines with whole-tone turns when they want a quick burst of unreality before landing back on a blues or bebop phrase.

Film composers picked up that torch too. Think of:

- John Williams' floating woodwind lines in “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” and “E.T.”

- Alan Silvestri's mysterious clarinet figures in “Van Helsing” and “The Mummy Returns” scores.

- Howard Shore's darker, suspended clarinet colors in “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy.

None of these scores may say “E whole-tone scale” on the page, but clarinetists recording them for orchestras from the London Symphony Orchestra to the New York Philharmonic will recognize the feeling: equal steps, sliding color, no obvious home base until the final, grounded note.

The E whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet uses exactly 6 distinct notes before repeating: E, F#, G#, A#, C, and D. That perfect symmetry is why it feels like it floats without a clear tonal center, ideal for impressionist passages and modern jazz improvisation.

From impressionism to jazz clubs: a short history of this scale

Whole-tone thinking existed in folk music and non-Western traditions long before it had a formal name in conservatories. But in European art music, it really caught fire with late 19th century composers. Debussy, Ravel, and Alexander Scriabin fell in love with the blurred boundaries that whole-tone material created. Clarinetists in Paris, playing Buffet-Crampon and early Martin Freres instruments, suddenly needed to glide through strings of whole steps with perfect evenness.

By the time early 20th century orchestras like the Orchestre de la Societe des Concerts du Conservatoire and the Vienna Philharmonic started performing these scores regularly, clarinetists had quietly added symmetric scales to their daily practice. The E whole-tone scale fit neatly into many woodwind keys, bridging clarion and altissimo in a way that made it a favorite for color runs.

Then jazz arrived. In the swing era, artists such as Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw noticed that whole-tone runs sounded fantastic over dominant chords with raised 5ths or 9ths. They used them as spicy passing material over standards like “Body and Soul” or “All the Things You Are.” Bebop players such as Buddy DeFranco pushed this further, turning whole-tone fragments into hard-swinging patterns at blistering tempos.

Later, modernists like Messiaen and Pierre Boulez baked whole-tone patterns into their harmonic language. Clarinet parts in works like Messiaen's “Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum” and Boulez's “Domaines” demand absolute comfort in symmetric scales. Players like Pierre Lefebvre and Eduard Brunner, who championed this repertoire, treated E whole-tone as non-negotiable daily vocabulary.

In contemporary clarinet music, from Jorg Widmann's “Fantasia” to John Adams' “Gnarly Buttons,” the whole-tone color appears in solo lines, ensemble riffs, and even extended techniques. Whether you play in a conservatory orchestra, a klezmer band, or an indie jazz trio, knowing how E whole-tone feels under your fingers connects you to all of these eras at once.

| Scale Type | Note Pattern (from E) | Typical Mood |

|---|---|---|

| E major | E F# G# A B C# D# | Bright, confident, lyrical |

| E minor | E F# G A B C D | Reflective, darker, serious |

| E whole-tone | E F# G# A# C D | Dreamy, unstable, otherworldly |

How the E whole-tone scale feels to play and hear

The first time you run the E whole-tone scale up and down, it can feel like the floor shifted slightly. There is no normal leading tone. Every note is equal. That symmetry gives the clarinet a slippery, almost glassy sound, especially around throat tones and clarion A and B.

Emotionally, this scale can feel:

- Dreamy, like late-night city lights reflected on wet pavement

- Playful, when used in fast, tumbling runs

- Slightly eerie, when repeated slowly with vibrato and soft dynamics

- Weightless, as if the clarinet line could float forever without landing

For improvisers, E whole-tone is a favorite color over E7#5, B7b5, or altered V chords. For classical players, it turns scale work into an expressive study in legato, embouchure control, and tone shading. For film and theater musicians, it is a quick way to create suspense without resorting to harsh dissonance.

Why this scale matters for your playing

So why should a Bb clarinet player, whether practicing on a student plastic instrument or a vintage Martin Freres grenadilla clarinet, spend time with the E whole-tone scale fingering chart?

Because this single pattern quietly strengthens several things at once:

- Even finger movement over challenging combinations like side F# and forked G#

- Control in register shifts between throat tones, clarion, and early altissimo

- Comfort in modern harmony, so Ravel, Messiaen, and jazz charts feel less intimidating

- Ear training for symmetrical patterns, which improves intonation awareness and phrasing

Mastering the E whole-tone scale fingering also prepares you for repertoire that looks intimidating at first glance. Those strange-looking runs in Debussy, the fast chromatic bursts in Copland's “Clarinet Concerto,” or the sliding lines in John Williams scores suddenly feel logical once your fingers and ears know this sound.

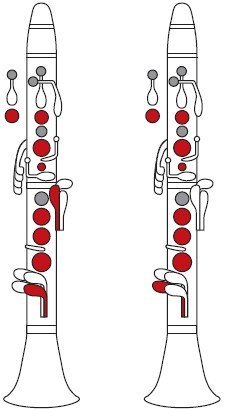

Quick technical notes: reading the E whole-tone fingering chart

The fingering chart you will receive for the E whole-tone scale focuses on clear, practical diagrams so your mind can stay on the sound. You will see:

- Standard Boehm-system fingerings for E, F#, G#, A#, C, and D across relevant registers

- Suggested alternates for G# and A# to help smooth difficult transitions

- Register key choices that keep the tone even as you move into clarion and early altissimo

Think of it less as a technical drill and more as a color exercise. Keep the embouchure relaxed, fingers close to the keys, and listen for one continuous line of sound, the way Sabine Meyer shapes passages in Debussy's “Premiere Rhapsodie” or the way Benny Goodman glides through fast altered runs on a V7 chord.

Simple practice ideas for making this scale musical

To help you really live inside the E whole-tone sound, here is a light practice routine. It is structured, but always listen like you are already on stage at the Concertgebouw or in a smoky jazz club with Artie Shaw.

| Practice Element | Time | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Slow E whole-tone, 2 octaves | 5 minutes | Perfect legato, steady air, tuning between each whole step |

| Rhythm variations (triplets, dotted) | 5 minutes | Finger clarity and rhythmic control |

| Small patterns (3 or 4-note cells) | 5 minutes | Building phrases you can use in solos and cadenzas |

| Apply to a real piece | 5 minutes | Spot whole-tone fragments in Debussy, Ravel, or jazz charts |

- Play the scale slowly in long tones, up and down, with a tuner, aiming for even color on every note.

- Break it into 3-note patterns (E-F#-G#, F#-G#-A#, etc.) and move them up and down the clarinet.

- Improvise a short 4-bar phrase using only E whole-tone, then land on a strong note in E major or E minor to feel the contrast.

For more scale stories and free fingering charts, you might also enjoy the pages on the Bb clarinet G major scale, the Bb clarinet chromatic scale, and our guide to clarinet alternate fingerings that smooth out tricky passages.

Key Takeaways

- Use the E whole-tone scale fingering chart to build smooth, even technique across challenging finger combinations.

- Listen to Debussy, Ravel, Benny Goodman, and Martin Frost to hear how this scale shapes color and emotion.

- Practice short whole-tone patterns and then spot them in your orchestral, chamber, and jazz repertoire.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet E whole-tone scale fingering?

On Bb clarinet, the E whole-tone scale uses the notes E, F#, G#, A#, C, and D arranged in whole steps only. The fingering pattern moves smoothly through chalumeau and clarion registers, with optional alternates for G# and A#. It is used to build fluid technique and modern harmonic color.

How is the E whole-tone scale different from E major on clarinet?

E major uses a mix of whole and half steps, with a clear tonal center and leading tone. The E whole-tone scale has only whole steps and no leading tone, which removes normal tension and release. This creates a floating, ambiguous sound that composers and improvisers use for dreamy or mysterious passages.

Which composers use the E whole-tone sound for clarinet?

Composers such as Debussy, Ravel, Scriabin, Messiaen, and Boulez often use whole-tone patterns around E in their clarinet writing. You will hear similar colors in works by Corigliano, Tomasi, Hillborg, and John Williams. Orchestral, chamber, and film scores all benefit from this shimmering harmonic language.

How should I practice the E whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet?

Start slowly with long tones on each note, focusing on even tone and intonation. Then add rhythmic patterns, 3-note and 4-note cells, and register changes. Finish by applying the scale to real music, such as passages in Debussy or short improvisations over E7 or B7 chords, to make it feel musical.

Is the E whole-tone scale only useful for advanced clarinetists?

No. Even early intermediate players can benefit from it. The fingerings are mostly familiar, and the pattern builds coordination, ear training, and confidence with modern sounds. Advanced players use it constantly in orchestral excerpts, contemporary pieces, and jazz solos, but it is valuable at every level.