If you have ever picked up a Bb clarinet and softly played those four notes that begin “Frere Jacques,” you already know the quiet magic of this little song. It is often the first full melody a player conquers, yet it carries centuries of stories, street corners in Paris, sleepy practice rooms, and concert halls from Vienna to New York.

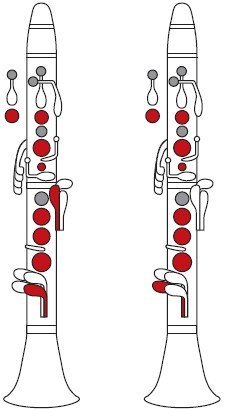

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

A Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide that shows every note of the Frere Jacques melody with exact Bb clarinet fingerings. It helps beginners play the tune accurately, build steady breath and finger control, and gain confidence for more advanced clarinet music.

The quiet power of Frere Jacques on Bb clarinet

On clarinet, “Frere Jacques” feels like a friendly handshake. The melody sits right in the comfortable throat and clarion registers, where the instrument speaks easily and the reed does not fight you. In French conservatories, private studios in New York, and youth bands across Europe, teachers reach for this tune when they want a student to feel like a real musician, not just a person doing long tones.

Think of a first lesson with a young player at the Paris Conservatoire in the early 1900s, using a French-made clarinet with ring keys and a warm, woody voice. The teacher does not begin with Mozart right away. Instead, they whisper: “Play these four notes after me” and suddenly the small studio fills with “Frere Jacques” in unison. It sounds simple, but to that student it is a door opening.

The Frere Jacques melody is built from 4 short phrases, each using about 5 to 7 distinct notes on Bb clarinet. That compact range makes it perfect for building secure hand position, steady air, and musical phrasing on a familiar melody.

From Paris streets to clarinet studios: the journey of Frere Jacques

“Frere Jacques” began life as a French nursery song, probably in the late 18th or early 19th century. While no one can say with certainty who wrote it, the melody likely spread through oral tradition: sung by children, copied by choir directors, and eventually written into songbooks that found their way into salons where early clarinets were starting to sing.

Imagine someone like Anton Stadler, Mozart's friend and clarinet muse, hearing simple street tunes on his way to rehearsal. Stadler was famous for improvising and ornamenting melodies on his extended-range clarinets. A song like “Frere Jacques” would have been perfect raw material for decorative variations, with trills, mordents, and wide leaps that showed off the clarinet's warm chalumeau and bright clarion registers.

By the time Romantic virtuosos like Heinrich Baermann and Carl Baermann were working with Carl Maria von Weber on soaring clarinet concertos, “Frere Jacques” had already settled into the European folk vocabulary. Teachers adapted it into beginner method books, just as Weber adapted folk-like themes into his Concerto No. 1 for clarinet and orchestra. One melody lived in simple quarter notes, the other in fiery arpeggios, but both shared that singable, memorable shape.

As clarinets evolved from early 5 or 6 key instruments to the Boehm-system clarinets we know today, the tune came along for the ride. In 20th century Europe, you could hear “Frere Jacques” on wooden Martin Freres clarinets in school bands, on buffet-style instruments in conservatories, and in small-town wind ensembles where amateur clarinetists learned their first melodies after work.

How great clarinetists turned a nursery song into a playground

Few legendary clarinetists built their careers on “Frere Jacques” itself, yet almost all of them touched this tune at some point, if only in a warmup, a masterclass, or a playful encore. What they did with such a simple melody is where the real magic lives.

Take Benny Goodman, the King of Swing. On recordings like the 1938 Carnegie Hall concert with his big band, you hear how he could shape even the smallest phrase with breath and articulation. In rehearsals, he often transformed easy tunes into swing studies, adding off-beat accents and playful syncopation. Students inspired by Goodman still use “Frere Jacques” to practice that same light, bouncing swing articulation, focusing on the tongue position and steady diaphragmatic support that gave his sound such clarity.

Artie Shaw loved to paraphrase familiar melodies during solos. In some live broadcasts with his orchestra, he sneaks in fragments of children's songs as inside jokes. Dropping part of “Frere Jacques” into an improvised clarinet solo is a classic move: you quote the melody in the chalumeau register, then leap into bluesy embellishments in the clarion register, echoing Shaw's blend of lyricism and fireworks.

Classical giants use the tune differently. Sabine Meyer, known for her lyrical control in works like the Mozart Clarinet Concerto and the Brahms Clarinet Quintet, has spoken about long-line phrasing and the importance of singing on the reed. Teachers who studied her recordings often ask students to play “Frere Jacques” with the same care they would give the slow movement of Mozart K. 622: even air, gentle dynamic arches, almost no bump between notes.

Martin Frost, known for his theatrical performances of pieces like Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales” and Copland's Clarinet Concerto, encourages imagination in even the simplest materials. Imagine playing “Frere Jacques” as if it were a scene from a silent film score, with subtle crescendos and whispers of vibrato on long notes. Frost's blend of contemporary technique and classical clarity makes even a nursery song feel like a tiny soundscape.

Klezmer greats like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer sometimes use well-known children's songs as vehicles for ornamentation. Listen to Feidman's recording of traditional tunes for clarinet and ensemble: he bends pitches, slides between notes, and uses expressive vibrato on open G and A that could easily be applied to a phrase of “Frere Jacques.” Krakauer's work with ensembles like Klezmer Madness shows how a simple tune can explode into wails, growls, and laughing trills using glissandi, half-holes, and expressive embouchure control.

Where Frere Jacques hides in great pieces and recordings

“Frere Jacques” has a famous cameo in orchestral literature: the third movement of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 1. There, Mahler takes the melody, slows it, and turns it into a dark minor-key funeral march. While the main solo goes to the double bass, clarinetists in orchestras from the Berlin Philharmonic to the New York Philharmonic sit surrounded by that twisted nursery tune, answering and coloring the theme with soft chalumeau notes.

The idea of transforming “Frere Jacques” into a minor-mode meditation has inspired many clarinet teachers. They ask students to play it in minor on clarinet, focusing on tone color and half-step intonation. That echoes Mahler's orchestrations and trains the ear for chromatic scales and expressive dynamics, skills needed for works like the Brahms Clarinet Trio or Debussy's “Premiere Rhapsodie.”

In jazz, you can find recordings where modern clarinetists like Anat Cohen or Ken Peplowski quote children's songs mid-solo in live performances. While not always labeled, fragments of “Frere Jacques” appear as a wink to the audience. Over a 12-bar blues or a standard like “All of Me,” this simple tune becomes a playground for blue notes, swing eighth notes, and call-and-response phrasing.

Film and television soundtracks also lean on the melody. Several European films set in childhood or boarding schools use clarinet to voice the tune, often with a solo Bb clarinet over strings. The clarinet's soft chalumeau matches the nostalgic feeling of the story. The same gentle sound you use on “Frere Jacques” in a practice room is the one composers reach for when they want memories and innocence on screen.

Chamber music arrangements are everywhere too. Clarinet trios, clarinet and piano duets, and school ensembles publish sets of folk song variations that include “Frere Jacques”. You might see it paired with other melodies in a suite that sits next to Mozart arrangements or simplified versions of the Weber Concertino. In those books, the tune becomes a stepping stone from folk material to classical repertoire.

| Use of Frere Jacques | Famous Context | What a clarinetist learns |

|---|---|---|

| Minor-key version | Mahler Symphony No. 1 | Tone color, minor scales, dark chalumeau sound |

| Swing variation | Benny Goodman style quotes | Swing feel, articulation, rhythmic play |

| Klezmer-style ornaments | Giora Feidman, David Krakauer | Pitch bends, slides, expressive vibrato |

Why this tiny song matters so much to clarinet players

On paper, “Frere Jacques” is simple. On clarinet, it becomes a lesson in breath, connection, and imagination. Because the tune is so familiar, your brain stops worrying about which note comes next. That frees your ears to listen to tone quality, tongue placement, and the way your left and right hands move as one over the tone holes and keys.

Emotionally, the melody feels like waking up slowly: the first phrase is a call, the second answers, the third wanders a bit higher, and the last phrase brings you home. On Bb clarinet, that arc lines up with a gentle climb from low G and A up into the middle register. Players often describe a sense of comfort and nostalgia when they shape those phrases, even at a very early level.

Advanced players use “Frere Jacques” as a sketch pad. They experiment with vibrato on long notes, try alternate fingerings for smoother slurs, or float a pianissimo tone on throat A and B-flat. The melody becomes a blank canvas for tone experiments, much like long tones, but with the added emotion of a song people recognize.

What mastering Frere Jacques on clarinet opens up for you

Learning “Frere Jacques” with a clear clarinet fingering chart sounds simple, but it quietly prepares you for much bigger pieces. The tune teaches you to move cleanly between throat tones and clarion notes, a skill you need for Mozart's Clarinet Concerto and the Weber Concertino. Those early shifts between A, B-flat, C, and D become the same coordination you use later in fast passages by Brahms or Debussy.

Because the melody is often played in a round, you also learn to listen. When two clarinets or a clarinet and flute play “Frere Jacques” as a canon, you practice balance, intonation, and ensemble timing. That prepares you for clarinet choir arrangements and wind band parts with close harmonies, like in Holst's “First Suite in E-flat” or Vaughan Williams's “English Folk Song Suite.”

For improvisers, this tune becomes an entry point to jazz and world music. Take the same notes, add a swing feel, and you are training the tongue and fingers for Benny Goodman solos. Turn it minor, add ornamentation and bends, and you are planting the seeds of klezmer phrasing that shows up later in Eastern European tunes or in works by composers like Osvaldo Golijov, who write clarinet parts rich in folk inflections.

Spending just 5 to 10 minutes each practice session on “Frere Jacques” variations can improve your tone, finger coordination, and rhythmic control more than another page of mechanical exercises alone.

A quick, friendly word about the Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart

The free Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart lays out every note of the melody with clear Bb clarinet fingerings, so you do not have to guess which ring key or side key to use. Most of the tune sits around open G, A, B, and C, with gentle steps into the clarion register that help you feel how the register key reshapes the air column in the bore.

Use the chart as a visual anchor while your ears and fingers do the real work. Keep your left-hand index, middle, and ring fingers curved, rest the right thumb under the thumb rest with relaxed pressure, and let the register key feel like an extra finger rather than a separate motion. The chart shows you where to put your fingers; your breath and imagination turn it into music.

- Scan the whole Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart once before you play.

- Practice the melody slowly, one phrase at a time, watching your left-hand position.

- Add the round: record yourself, then play along as a second voice.

- Try one variation: minor key, swing rhythm, or soft-as-possible dynamics.

| Practice Focus | Time | How often |

|---|---|---|

| Slow melody with chart | 3 minutes | Every practice day |

| Round with a partner or recording | 3 minutes | 2 to 3 times per week |

| Creative variation (minor, swing, ornaments) | 4 minutes | 1 to 2 times per week |

Troubleshooting Frere Jacques on Bb clarinet

Even a simple melody can highlight small issues with embouchure, hand position, and breath support. Use “Frere Jacques” as a friendly mirror: if something feels awkward here, it will show up later in more demanding pieces too.

| Problem | Likely cause | Quick fix while using the chart |

|---|---|---|

| Notes crack between registers | Unsteady air or late register key | Blow through the change, press the register key a split second before the fingers move. |

| Fuzzy throat tones (G, A, B-flat) | Loose embouchure or low tongue position | Firm lower lip against the reed, imagine saying “ee” inside your mouth as you play. |

| Uneven rhythm in the round | Rushing quarter notes, no internal pulse | Tap your foot, count “1 2 3 4” out loud, and use a metronome while following the chart. |

Key Takeaways

- Use the Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart to free your mind from guessing fingerings so you can focus on tone and phrasing.

- Treat this simple melody like a miniature Mozart adagio: shape every phrase, listen for balance, and enjoy the sound of your Bb clarinet.

- Return to Frere Jacques often as a warmup, a creativity lab, and a gentle bridge toward concertos, chamber music, and jazz solos.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart?

A Frere Jacques clarinet fingering chart is a visual map that shows every note of the Frere Jacques melody with the correct Bb clarinet fingerings. It helps beginners start with confidence, supports accurate hand position, and gives advancing players a simple framework for tone, phrasing, and creative variations.

Is Frere Jacques good for beginner clarinet players?

Yes. Frere Jacques is ideal for beginners because it uses a small, comfortable range and steady rhythms. It teaches clear finger motion on the main tone holes, relaxed embouchure on throat tones, and basic phrasing. Once you can play it smoothly with a chart, you are ready for many other folk tunes and easy classical pieces.

How can I make Frere Jacques sound more musical on clarinet?

Think in phrases, not just notes. Breathe before each four-bar idea, add a slight crescendo to the middle of each phrase, and release softly. Listen to lyrical clarinetists like Sabine Meyer or Richard Stoltzman, then imitate their legato and color on this simple melody.

Can I use Frere Jacques to practice jazz clarinet?

Absolutely. Keep the same fingerings from the chart, but play the rhythm with swing eighth notes and a light tongue, in the style of Benny Goodman or Artie Shaw. Add a few blue notes and grace notes, and you have a safe way to experiment with jazz phrasing without learning new material.

How often should I practice Frere Jacques on Bb clarinet?

Short, regular sessions work best. Spend 5 to 10 minutes on Frere Jacques at the start or end of practice, several times per week. Use that time to refine tone, experiment with dynamics, and play it as a round or in different styles. It stays useful long after the beginner stage.

For more on clarinet history, artistry, and playing joyfully, explore other Martin Freres articles on classic clarinet repertoire, tone development, and the evolution of Bb clarinet design.