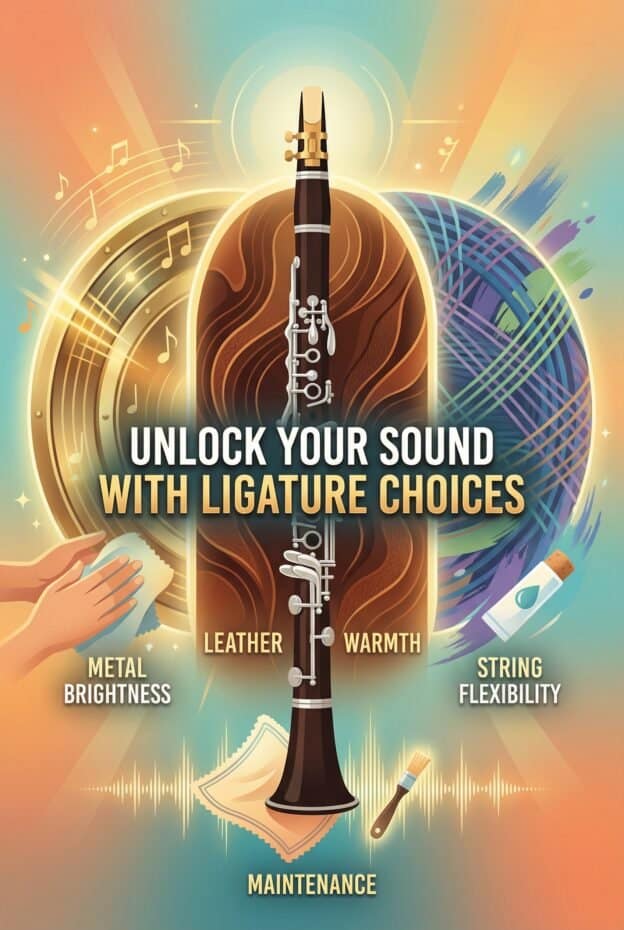

A ligature secures the reed to the mouthpiece and materially affects reed vibration. Metal ligatures such as brass, silver, and nickel-plated models usually give a brighter, more projecting tone, while leather and gut tend to sound warmer and fuller. Synthetic and fabric designs offer a balanced response and better humidity resistance. Choose by the warmth vs projection you want and by how much maintenance you are willing to do.

What is a ligature and why it matters (role in reed vibration and sound production)

A ligature is the device that holds the reed against the mouthpiece table so the reed can vibrate freely. It looks simple, but its material, shape, and pressure pattern influence how the reed starts, sustains, and stops vibrating. That changes tone color, projection, articulation clarity, and overall ease of playing on the clarinet.

On a clarinet mouthpiece, the ligature wraps around the mouthpiece and reed, usually with one or two screws. It must secure the reed without crushing it. The ideal ligature distributes pressure evenly along the reed's stock while leaving the vamp free to vibrate. Small changes in pressure pattern can shift the balance between warmth, brilliance, and response.

Instrument makers and acousticians describe the ligature as part of the reed-mouthpiece system. The reed, table, rails, and facing curve form a vibrating unit. The ligature's material stiffness and contact area alter how energy flows from the reed into the mouthpiece and how quickly the reed can respond to air and tongue strokes.

For advanced clarinetists, the ligature becomes a fine-tuning tool. Once reed strength, cut, and mouthpiece are chosen, ligature material can subtly shift brightness, articulation snap, and resistance. Teachers often use ligature changes to help students find easier response or a more focused sound without changing the entire setup.

A brief history of ligature materials (from gut/string to 19th-century metal ligatures – Martin Freres in historical context)

Early single-reed instruments such as the chalumeau and early clarinets used simple string or gut bindings instead of modern ligatures. Players wrapped waxed string or thin gut around the reed and mouthpiece to hold the reed in place. This flexible, low-mass solution allowed the reed to vibrate freely but required careful tying and frequent adjustment.

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as clarinet keywork and bore design evolved, makers began experimenting with more durable ligature systems. Metal bands with screws appeared in France and Germany. Brass and nickel silver were common because they were easy to form, could be plated, and held up well to daily use in orchestras and military bands.

In the 19th century, French makers such as Buffet-Crampon and others adopted metal ligatures on many professional clarinets. Historical instruments in European museum collections show a variety of early designs, including simple bands with a single screw and more elaborate two-screw models that allowed finer pressure control across the reed.

As clarinet playing spread through military bands, salons, and concert halls, metal ligatures became standard because they were quick to adjust and more consistent than hand-tied string. Leather and fabric wraps appeared later as players searched for warmer, less metallic tone colors, especially in French and German orchestral traditions.

By the late 20th century, manufacturers introduced synthetic, fabric, and hybrid ligatures. These designs combined flexible materials with adjustable plates or rails, giving players more ways to fine-tune contact area and pressure. Today, serious clarinetists often own several ligatures of different materials to match varied repertoire, halls, and reeds.

Comparing ligature materials: metal, leather, gut/string, synthetic, fabric, rubber/plastic

Ligature material affects stiffness, mass, and friction at the reed contact points. Those three factors shape how the reed starts and sustains vibration. While individual designs vary, players and acousticians have identified consistent trends for each major material family on the clarinet.

Metal ligatures (brass, silver, nickel-plated, stainless)

Metal ligatures, often made from brass, nickel silver, or stainless steel, are relatively rigid and low in damping. They usually have a defined contact plate or rails that press on the reed stock. This rigidity tends to produce a focused, projecting sound with strong core and clear articulation, especially in the upper register.

Brass and nickel-plated ligatures often sound bright and direct. Silver-plated models can feel slightly smoother in attack, though differences are subtle. Stainless steel designs may feel very immediate, with fast response to articulation. Many jazz and solo clarinetists choose metal ligatures for their cut and projection in amplified or large-ensemble settings.

Leather ligatures

Leather ligatures wrap a band of leather around the mouthpiece and reed, often with a metal or plastic plate inside. Leather is more flexible and has higher internal damping than metal. This often yields a warmer, rounder tone with slightly softened articulation edges and a sense of cushion under the air stream.

Many orchestral clarinetists like leather for its blend and control in soft dynamics. Leather can tame harshness on bright mouthpieces or strong reeds. However, it can stretch over time, especially when exposed to moisture, so fit and pressure may change. Players must monitor screw travel and reed security as the leather ages.

Gut and string ligatures

Gut and string ligatures are the historical predecessors of modern designs. Today they remain a niche choice for period performance or players who prefer a very flexible, low-mass solution. Waxed string or thin gut is wrapped several turns around the reed and mouthpiece, then tied or tucked to hold tension.

These ligatures can give a very free, resonant vibration with a natural, singing quality. The sound often feels open and flexible, with easy color changes. The tradeoff is that they are slower to adjust, sensitive to humidity, and less consistent from day to day. They demand careful technique to tie with even pressure.

Synthetic ligatures (composite, molded, high-tech materials)

Synthetic ligatures use engineered materials such as composite resins, high-strength plastics, or carbon-infused polymers. They are designed to balance rigidity and damping. Many have adjustable plates or interchangeable inserts that let the player change the contact pattern on the reed.

These ligatures often give a centered tone with moderate warmth and good projection. They tend to be more stable than leather in humid conditions and more forgiving than metal on bright mouthpieces. For doublers and students, synthetics can offer reliable performance with relatively low maintenance and consistent fit.

Fabric ligatures

Fabric ligatures use woven or knit material such as nylon, polyester, or blended fibers. They usually have a small metal or plastic frame and a screw or slide mechanism to adjust tension. The fabric conforms closely to the reed and mouthpiece, spreading pressure smoothly.

Players often describe fabric ligatures as producing a dark, smooth tone with easy low-register response. Articulation may feel slightly softer compared with rigid metal models. Fabric designs can be excellent for beginners because they are forgiving of minor alignment errors and less likely to crack reeds during adjustment.

Rubber and plastic ligatures

Rubber and basic plastic ligatures are common on student clarinets. They are light, inexpensive, and resistant to corrosion. Some use a simple band design that stretches over the reed and mouthpiece, while others combine elastic material with a small screw or clip.

These ligatures generally produce a neutral to slightly warm sound with moderate projection. Their main advantage is durability and simplicity, not ultimate tonal refinement. For serious players, they can serve as reliable backups or practice ligatures, while a more specialized metal, leather, or synthetic model is used for performance.

How ligature material and flexibility affect sound, projection, and articulation

Ligature material affects sound by changing how the reed is constrained at its base. A stiffer, less damping material such as brass allows more high-frequency energy to radiate, which the ear perceives as brightness and projection. Softer, more damping materials such as leather or fabric absorb some of that energy, emphasizing warmth and smoothness.

Flexibility also matters. A very rigid ligature clamps the reed firmly, which can improve focus but may choke vibration if overtightened. A more flexible ligature allows micro-movements at the reed stock, which can feel more forgiving under the embouchure and air. That can help legato and dynamic nuance but may reduce extreme projection.

Projection is tied to how much upper partial content reaches the listener. Metal ligatures often emphasize clarity at a distance, especially in large halls. Leather and fabric ligatures may sound ideal under the ear but slightly less cutting in the back of the hall. This is why some players choose one ligature for practice and another for performance.

Articulation response depends on how quickly the reed can start and stop vibrating when the tongue touches and releases. Rigid, low-damping ligatures often feel crisp, with clear attacks and short note lengths available on demand. Softer ligatures can give a more legato feel, with slightly rounded attacks that suit lyrical playing and soft entrances.

Flexibility also affects register balance. Some ligatures make the throat tones feel more open, while others stabilize the upper clarion and altissimo. If a setup feels uneven, experimenting with a different ligature material or contact pattern can sometimes even out the registers without changing reeds or mouthpiece.

Choosing the right ligature: matching material to reed, mouthpiece, genre, and player goals

Choosing a ligature starts with your existing setup. The same ligature behaves differently on a narrow French-style mouthpiece than on a larger tip-opening jazz mouthpiece. Reed strength, cut, and cane density also interact with ligature stiffness. Think of the ligature as a fine-tuning tool that adjusts how your current setup behaves.

Matching ligature to reed and mouthpiece

If you use soft reeds or a very open mouthpiece, a rigid metal ligature can add needed focus and stability. It helps prevent the reed from feeling too loose or buzzy. On the other hand, if you play strong reeds on a resistant mouthpiece, a softer leather or fabric ligature can reduce harshness and make response more forgiving.

Some mouthpieces have pronounced side rails or unusual table shapes. In these cases, a ligature with adjustable plates or flexible bands may seat more securely than a rigid metal cage. Always check that the ligature sits squarely and that the contact points are on the reed stock, not on the vamp or tip.

Genre and ensemble considerations

For orchestral and chamber music, many clarinetists favor leather, fabric, or flexible synthetic ligatures. These materials support a warm, blended tone that integrates well with strings and winds. They also help with soft attacks and controlled pianissimo playing, which are important in classical repertoire.

For jazz, klezmer, and solo work where projection and edge are prized, metal ligatures are common. Brass or nickel-plated models can give the brilliance and punch needed to cut through rhythm sections or amplified instruments. Some players keep a brighter metal ligature specifically for lead or solo roles.

Player goals and comfort

If your goal is maximum color control and subtle shading, a slightly more flexible ligature such as leather or a well-designed synthetic often feels best. It lets you shape the sound with embouchure and air without the tone becoming too edgy. If you value immediate response and clarity above all, a rigid metal design may suit you better.

Comfort and confidence also matter. Some players simply feel more secure with a ligature that holds the reed very firmly. Others prefer the feel of a softer wrap that seems to breathe with the reed. Try several materials and notice not only the sound but how the instrument responds to your air and tongue.

Maintenance and workshop steps for each material (leather break-in, moisture care, checking stretch, replacement tips)

Ligature maintenance protects both sound quality and reed security. Each material has specific needs. Regular inspection prevents problems such as uneven pressure, reed slippage, or corrosion that can damage reeds and mouthpieces. A simple maintenance routine can extend the life of your ligature and keep your setup consistent.

Metal ligatures: cleaning and corrosion checks

For metal ligatures, wipe the inside surfaces and screw area weekly with a soft, dry cloth to remove moisture and reed fibers. If you see greenish corrosion on brass or flaking on plated surfaces, clean gently with a non-abrasive metal polish, keeping polish away from the reed contact area and mouthpiece.

Check screws monthly for smooth travel. If they bind, add a tiny drop of light machine oil to the threads, then wipe off excess. Inspect contact plates or rails for burrs that could scratch reeds. If a plate is bent or uneven, a repair technician can often re-flatten it so pressure is even again.

Leather ligatures: break-in and moisture care

New leather ligatures often feel stiff. For break-in, install the ligature on the mouthpiece without a reed and gently flex the leather by tightening and loosening the screws several times. Then install a reed and play short sessions, gradually increasing tension until the leather conforms to the mouthpiece shape.

Avoid soaking leather. After playing, wipe off moisture and allow the ligature to dry in open air, away from heat sources. If the leather becomes saturated, blot gently with a towel and let it dry slowly. Conditioners are rarely needed and can soften the leather too much, increasing stretch and reducing stability.

Check for stretching by noting screw position. If you must tighten much farther than when the ligature was new, the leather may have stretched. When the screws bottom out or the ligature no longer holds the reed securely at normal tension, it is time to replace it.

Gut and string ligatures: humidity and lifespan

Gut and string ligatures are sensitive to humidity. Store them in a dry case compartment and avoid leaving them under tension when not in use. If gut absorbs moisture, it can swell and lose strength. Replace gut that shows fraying, discoloration, or thinning, as it can break suddenly under tension.

Waxed string lasts longer but still needs inspection. If knots slip or the string becomes fuzzy, re-tie with fresh material. Many period performers prepare several pre-cut lengths of gut or string so they can replace a worn ligature quickly before a concert.

Synthetic and fabric ligatures: cleaning and wear

Synthetic and fabric ligatures should be cleaned periodically to remove saliva and reed residue. Every few weeks, wipe them with a slightly damp cloth. For heavier buildup, use mild soap and lukewarm water, then rinse and air dry completely before use. Avoid hot water, which can warp plastic parts or weaken adhesives.

Inspect fabric for fraying, especially at edges that contact the reed. If threads begin to pull or the fabric loses elasticity, response may become inconsistent and reed security may suffer. Replace when you notice difficulty maintaining stable tension or when fraying reaches the contact area.

Rubber and plastic ligatures: deformation checks

Rubber and plastic ligatures are low maintenance but can deform over time. Check that the band still sits squarely and does not tilt the reed. If the material cracks, hardens, or warps so that pressure is uneven, replace it. Clean with mild soap and water only, and avoid solvents that can weaken the material.

Practical fitting and adjustment techniques (even pressure, screw tension, alignment, testing methods)

Proper ligature fitting is as important as material choice. Even the best ligature will underperform if it is misaligned or overtightened. A consistent fitting routine helps you evaluate ligature differences accurately and keeps reeds vibrating at their best on the clarinet.

Basic alignment steps

Start by placing the reed on the mouthpiece table with the tip aligned or just barely visible. Hold the reed in place with a thumb, then slide the ligature down from the top. Center the ligature so it is parallel to the mouthpiece rails and not twisted. The screws should be on the side or back, depending on design.

Position the ligature so its lower edge sits just above the end of the mouthpiece table, usually 1 to 3 millimeters above the bottom of the reed stock. Too low and it may clamp the reed excessively; too high and the reed may slip or vibrate unevenly. Check that contact points are on the reed stock, not the vamp.

Screw tension and even pressure

Tighten screws until the reed no longer slides when gently nudged, then add a small additional turn. On two-screw ligatures, alternate between screws so pressure builds evenly. The goal is secure but not crushed. If you see the reed bending or hear a dulling of tone as you tighten, you have gone too far.

Some players use a simple test: play a long tone, then slightly loosen the ligature until the sound becomes unstable, then tighten just enough to regain stability. This finds a minimum effective tension for that reed and ligature. Marking typical screw positions mentally helps you return to a reliable setting.

Testing methods for fine adjustment

After basic alignment, test response with short exercises. Play soft attacks in the low register, then staccato in the clarion, and slurred leaps across the break. If low notes are unstable, try moving the ligature slightly lower. If high notes feel pinched, try moving it slightly higher or reducing tension.

Experiment with very small changes, about 1 millimeter at a time. Note how each move affects tone and response. Over time, you will learn where each ligature tends to work best on your mouthpiece. This knowledge makes it easier to switch reeds quickly while keeping your sound consistent.

Troubleshooting common ligature problems (reed slippage, harsh tone, dull response, uneven vibration)

When sound or response changes suddenly, the ligature is often part of the cause. Systematic troubleshooting can save time and prevent you from blaming reeds or embouchure for issues that start at the reed-mouthpiece interface. Here are common problems and practical fixes.

Reed slippage

If the reed slides during playing or adjustment, first check ligature position. Make sure the ligature is not sitting on the curved part of the vamp. Move it slightly lower, closer to the end of the table. Then increase screw tension slightly while keeping pressure even on both sides.

If slippage continues, inspect the ligature interior. Very smooth metal or worn leather can have low friction. Some players lightly clean the reed stock and ligature interior to remove moisture and residue, which can act as a lubricant. If a leather ligature has stretched, it may no longer hold the reed securely and needs replacement.

Harsh or edgy tone

A harsh, overly bright sound can result from a very rigid ligature, excessive tension, or contact points that are too close to the vibrating vamp. Try loosening the ligature slightly and moving it 1 to 2 millimeters lower on the reed stock. If that does not help, test a more flexible material such as leather or fabric.

Also check for burrs or sharp edges on metal plates that may be digging into the reed. These create localized pressure that can distort vibration. A technician can smooth such edges. In some cases, pairing a bright mouthpiece and strong reed with a softer ligature material gives a better tonal balance.

Muffled or dull response

If the sound feels muted or resistant, the ligature may be too tight or too soft for the setup. First, slightly reduce screw tension and see if the reed becomes more responsive. If not, move the ligature a bit higher, closer to the vamp, while keeping it off the curved area.

If a leather or fabric ligature has become very soft or stretched, it can damp vibration excessively. Testing a more rigid ligature, such as metal or a firm synthetic, often restores clarity and projection. Also confirm that the reed itself is not waterlogged or worn out, as that can mimic ligature problems.

Uneven vibration across registers

When low notes speak well but the upper register feels tight, or vice versa, uneven pressure at the reed base is a common culprit. Check that the ligature is level and not tilted. On two-screw designs, adjust each screw to equal tension. Sometimes loosening the upper screw slightly while keeping the lower screw firm improves upper-register freedom.

If one side of the reed seems to respond less, inspect whether the ligature presses more on that side. Some players rotate the ligature slightly or choose a design with a different contact pattern to even out response. If problems persist, a mouthpiece facing or reed flatness issue may also need attention from a technician.

Buying, testing, and audition checklist (what to listen for and how to run quick comparative tests)

When auditioning ligatures, treat the process like testing mouthpieces or reeds. Use a structured checklist so you can compare materials fairly. Small differences can be hard to judge in the moment, especially when switching back and forth quickly on the clarinet.

Preparation before testing

Use a familiar mouthpiece and several reeds that you know well. Avoid testing ligatures with brand-new or unstable reeds. Warm up until your embouchure and air feel consistent. Then choose a short set of test passages that cover soft and loud dynamics, legato and staccato, and low and high registers.

Set each ligature with careful alignment and similar screw tension. If possible, have a teacher or colleague listen from several meters away, since projection differences may be more obvious at a distance than under your ear. Take brief notes after each ligature so impressions do not blur together.

What to listen and feel for

Listen for core and focus of sound, warmth vs brightness, and how easily the sound carries at mezzo forte and forte. Pay attention to attack clarity in staccato passages and the smoothness of legato connections. Notice how easily soft entrances speak and how stable long tones feel across the break.

Also evaluate comfort: Does the ligature make the setup feel more or less resistant? Do you feel you must work harder with air or embouchure to get your usual sound? A good ligature should support your natural playing rather than forcing you to adapt constantly.

Making a final choice

After initial trials, narrow the field to two or three ligatures and test them on different days. Our perception can change with fatigue or room acoustics, so repeated listening is valuable. If you perform in varied settings, test in a large room or hall when possible to judge projection.

Choose the ligature that best supports your main playing context. Some clarinetists keep two ligatures: one slightly brighter, often metal, for solo and jazz work, and one warmer, often leather or fabric, for orchestral and chamber music. Over time, you can refine your collection as your sound concept evolves.

Key Takeaways

- Ligature material and flexibility subtly but meaningfully affect clarinet tone, projection, and articulation by changing how the reed is held and how it vibrates.

- Metal ligatures tend to give brighter, more projecting sound and crisp attacks, while leather, gut, fabric, and some synthetics favor warmth, blend, and smoother response.

- Proper alignment, even screw tension, and regular maintenance often matter as much as material choice for stable reeds and consistent sound.

- Match ligature material to your mouthpiece, reeds, and musical goals, and use structured tests to compare options in real playing conditions.

FAQ

What is ligature?

A ligature is the device that holds the clarinet reed against the mouthpiece table so the reed can vibrate. It wraps around the mouthpiece and reed, usually with one or two screws, and its material and design influence tone, projection, and response by controlling how the reed is clamped.

How does ligature material affect clarinet sound?

Ligature material changes stiffness and damping at the reed base. Rigid metals like brass and nickel typically emphasize brightness, projection, and crisp articulation. Softer materials such as leather, fabric, and some synthetics absorb more high-frequency energy, often giving a warmer, smoother tone and more forgiving response.

Which ligature is best for classical versus jazz clarinet?

For classical clarinet, many players prefer leather, fabric, or flexible synthetic ligatures that support a warm, blended sound and controlled soft dynamics. For jazz or solo work, metal ligatures such as brass or nickel-plated models are common because they provide extra brilliance, focus, and projection in louder ensembles.

How do I maintain a leather ligature and prevent stretching?

Break in a leather ligature gradually by flexing it on the mouthpiece and playing short sessions. After use, wipe off moisture and let it air dry away from heat. Avoid soaking or heavy conditioners. Monitor screw travel; if you must tighten much farther than when new or the reed feels loose, the leather has likely stretched and needs replacement.

Why does my reed feel muted or harsh when I change ligatures?

A new ligature may clamp the reed differently, changing vibration. If the sound is muted, the ligature might be too tight or too soft for your setup, damping the reed. If it is harsh, the ligature may be very rigid or positioned too high. Adjust tension and position, or try a different material that better matches your mouthpiece and reeds.