If you grew up humming American folk tunes, you probably met “I've Been Working On the Railroad” long before you ever met a Bb clarinet. The magic happens when those childhood syllables suddenly turn into sound from your own mouthpiece and reed. That first time you play the melody cleanly, it feels like you have stepped inside the song instead of just listening from the outside.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

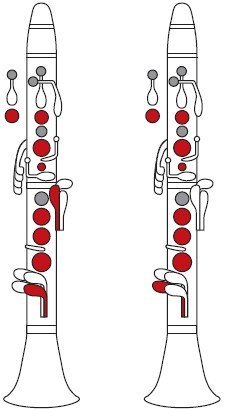

The “I've Been Working On the Railroad” clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide to every note needed for this folk tune on Bb clarinet. It shows simple, singable fingerings in staff notation and diagram form so players can focus on phrasing, tone, and joy instead of guesswork.

From Rail Yards To Reeds: How This Folk Song Reached The Clarinet

“I've Been Working On the Railroad” started as a work song, a steady pulse for people swinging hammers and laying track across the United States in the late 19th century. Long before anyone thought about chalumeau register or left-hand pinky keys, this melody lived in human voices, shouted in rhythm, often in harsh conditions.

As the song moved from labor camps to parlors and schoolrooms, it met the clarinet. Early American clarinetists, playing Albert-system instruments and simple Boehm-system Bb clarinets, would have used it as a friendly warm-up between more serious pieces. Picture a small-town band in 1900: a clarinetist finishing a Sousa march, then casually leaning into “I've Been Working On the Railroad” to make the cornet section smile.

Because the tune sits comfortably in a singable range, it mapped beautifully to the clarinet's chalumeau and lower clarion registers. That natural fit is why so many modern teachers still reach for it before moving on to more intense studies like the Rose Etudes or the Weber Concertino.

How Great Clarinetists Turn Simple Songs Into Storytelling

No one sells tickets to hear a full recital of “I've Been Working On the Railroad,” but listen closely to the way great clarinetists shape folk-like melodies and you will hear the same spirit. This little tune trains the instincts that later make audiences hold their breath during the softest phrase of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A major, K. 622.

Think of Anton Stadler, the clarinetist who inspired Mozart. Stadler reportedly had a warm, vocal tone and a gift for shaping simple lines. The same breath control and dynamic shading that would make the slow movement of the Mozart concerto float would make a humble railroad tune sound like a personal story told into the bell of the instrument.

Heinrich Baermann, a favorite of Carl Maria von Weber, helped bring lyrical writing for clarinet into the spotlight with pieces like Weber's Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor and the Concertino in E b. The singing style required for those solos is exactly the quality you can practice on “I've Been Working On the Railroad”: a smooth connection from note to note, a phrase that rises and falls like a human voice, and a line that always sounds like it means something.

Jump forward a century and listen to Benny Goodman. In his recording of “St. Louis Blues” or the famous Carnegie Hall concert, Goodman takes folk-like, bluesy fragments and turns them into joyful fireworks. If he had been handed “I've Been Working On the Railroad” at a jam, he would have treated it like raw material for swing: start with the plain melody, then bend notes, add syncopation, and fill in chords with arpeggios.

Artie Shaw, on records like “Begin the Beguine,” also shows how a straightforward tune can become something silky and elegant on Bb clarinet. The same embouchure that makes his high clarion register float can give a simple D in the staff a feeling of weight and color when you play a folk song quietly.

In the klezmer world, Giora Feidman and David Krakauer work a similar kind of magic. Listen to Feidman on traditional tunes like “Shalom Aleichem” or Krakauer on “Der Heyser Bulgar.” The melodies are often as direct and singable as “I've Been Working On the Railroad.” What makes them unforgettable is the expressive pitch inflection, the playful ornaments, and the story behind every note. Practicing a basic folk song with that kind of attitude turns your fingering chart into a script for storytelling.

Most classroom arrangements of “I've Been Working On the Railroad” for Bb clarinet use only 12 to 18 different pitches. That compact range lets students focus on tone, breath support, and phrasing instead of chasing extreme notes.

Where This Melody Hides In Concert Halls, Jazz Clubs, And Film Scores

You may not see “I've Been Working On the Railroad” printed on a Philharmonic program, but its energy keeps echoing through clarinet music. Folk-tune DNA shows up everywhere, from chamber music to movie soundtracks.

In classical repertoire, listen to the way Johannes Brahms shapes phrases in his Clarinet Sonata in F minor, Op. 120 No. 1, or the slow movement of the Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115. The lines are richer and more harmonically complex than a work song, but at their core they carry the same singable, steady pulse that makes a railroad tune feel grounded.

Sabine Meyer often brings that song-like approach to her recordings of Brahms and Mozart. Notice how she lets a single long note bloom, the way a singer might linger on a meaningful syllable. Take that same patience into your “Railroad” melody and suddenly your practice room becomes your own tiny concert hall.

Martin Frost does something similar in contemporary works like Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales.” Folk-like fragments appear, twist, and transform. The exaggerated dynamics and stage presence he uses there can absolutely be practiced on an unassuming folk song. Start with the plain melody from the fingering chart, then experiment: one verse pianissimo like Frost, the next fortissimo as if you were filling a full orchestra hall.

Jazz clarinetists treat simple themes as springboards. In addition to Goodman and Shaw, players like Buddy DeFranco showed how bebop language can grow from phrases that sound as clear as a schoolyard rhyme. Lines in tunes such as “Cherokee” or “Donna Lee” still rely on the listener grasping a melodic idea quickly, just like a child instantly recognizes “Someone's in the kitchen with Dinah.”

Film scores also borrow that sense of steady, rolling rhythm that fits a railroad. Think of how clarinet is used in Americana-style scores: the train scenes in classic Western films, or the light, nostalgic cues in family movies. Arrangers often reach for Bb clarinet because its chalumeau register can feel warm and woody, like old railroad ties and worn leather seats. Play your fingered notes with a bit of reverb in your imagination and you will start hearing your own movie soundtrack.

Folk arrangements for wind band often tuck fragments of “I've Been Working On the Railroad” or similar tunes into medleys. School bands using published charts sometimes feature the clarinet section on these lines because the tone color blends well with flutes and alto saxophones. So that simple fingering chart in front of you might be the first step toward holding a melody line in a full band or clarinet choir.

Then And Now: A Railroad Tune Across Clarinet Eras

In the late 1800s, while early American railroads expanded, European clarinetists were already shaping the modern technique we recognize today. Players like Baermann were refining articulation, embouchure, and fingerings on 13-key instruments, while workers in the United States sang rhythmic calls that would eventually become songs like “I've Been Working On the Railroad.” Two musical worlds existed side by side: the concert hall and the construction site.

By the early 20th century, as Bb clarinets from makers like Martin Freres spread into community bands and school programs, folk tunes became standard teaching material. A conductor could pass a handwritten part for “Railroad” to a young clarinetist and instantly connect with something the player had heard at home, on a phonograph, or from siblings around a family piano.

As jazz developed in New Orleans and Chicago, clarinetists such as Johnny Dodds and later Benny Goodman absorbed folk material into their ears even if they did not record this particular tune. The swing feel, the scoops, the glissando that Goodman made famous in “Sing, Sing, Sing” all serve the same purpose: turning a simple line into a personal statement.

In the later 20th century, clarinet pedagogy started to include more method books that combined scales with folk melodies. Teachers realized that a chart of little black dots on a staff works better when attached to something familiar. “I've Been Working On the Railroad” sits beside “When the Saints Go Marching In” and “Scarborough Fair” as a bridge between dry fingering charts and real music.

Today, even with digital tuners and streaming playlists, this song still shows up in beginner clarinet books, jazz combo arrangements, and folk sessions. A modern student might listen to Sabine Meyer playing the Mozart concerto in the morning, practice the “Railroad” melody at school in the afternoon, then hear a bluegrass version with fiddle and mandolin in the evening. The clarinet fingering chart becomes a map that links all those experiences.

| Era | Clarinet Use | How “Railroad” Fits |

|---|---|---|

| Late 19th century | Concertos by Weber, chamber music, town bands | Folk work songs circulate mostly by voice, clarinet is nearby in bands |

| Early 20th century | Marching bands, early jazz, school ensembles | Melody appears in band books as an easy student piece |

| Mid to late 20th century | Orchestras, big bands, clarinet choirs | Used in method books and folk medleys for Bb clarinet |

| 21st century | Classical, jazz, klezmer, film sessions, crossover projects | Appears in digital fingering charts, online lessons, and classroom arrangements |

Why This Tune Still Hits The Heart On Bb Clarinet

“I've Been Working On the Railroad” carries a double mood. On one side it feels playful and nostalgic, almost like a campfire song with kazoos and laughter. On the other, if you listen to the lyrics and the history, you can sense the weight of labor, repetition, and time. The clarinet is perfectly built to hold both sides at once.

In the chalumeau register, a low G or F played with a supported air stream and relaxed right-hand fingers can sound earthy and grounded, like a slow train leaving the station. Move up into the clarion register and the same melody brightens, like sunlight hitting the tracks. Players such as Richard Stoltzman show that ability to shift mood in their recordings of Aaron Copland's Clarinet Concerto, moving from open, pastoral sounds to jazzy, rhythmic drive. You can practice that emotional gear change on each phrase of this simple song.

The repeating lines also create a kind of meditation. Practicing the tune with a metronome, listening to every interval, becomes almost like breathing exercises. As your left-hand thumb taps between the register key and its resting spot, you start hearing how every small movement affects your sound. This is where a fingering chart turns into something emotional: it is literally a picture of how your hands shape feeling into sound.

What “I've Been Working On the Railroad” Gives You As A Player

For a beginner, this clarinet fingering chart is a doorway. You see simple notes on the staff, perhaps mostly in the middle of the staff: C, D, E, F, G, maybe an A above the staff. You match them to the diagram, feel the ring keys under your left index finger and the lower joint keys under your right-hand pinky, and suddenly you are playing something your grandparents might recognize.

For an intermediate player, the same tune becomes a tone laboratory. You can shape a crescendo over “I've been working” and then relax into “on the railroad” with a decrescendo. You can try single-tongue articulation on one verse and legato tonguing on the next. If you are working through the Baermann scale studies or Rose 32 Etudes, using this folk song in your warm-up keeps your musical heart awake while your fingers handle the drills.

For an advanced or professional clarinetist, this melody is a way to strip away ego. Play it with the same care you bring to the slow movement of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet. Focus on resonance at the mouthpiece, on how the barrel and upper joint vibrate in your hands, on how a tiny reed adjustment changes the timbre on an open G. That humility, learned from a work song, pays off in every Weber cadenza or orchestral solo you play.

A Brief Word On The Clarinet Fingering Chart For This Tune

Most arrangements of “I've Been Working On the Railroad” for Bb clarinet sit in a friendly key, often F major or B b major in concert terms. That means a lot of familiar positions: left-hand first finger for A, simple right-hand combinations for E and D, and maybe a first encounter with B b using the side key or the left-hand first finger plus right-hand first finger.

Use the free fingering chart as your visual anchor: check how the tone holes line up with the staff notation, then try to rely more on your ears and less on your eyes as you repeat the melody. The goal is not just to get the notes right, but to let your embouchure, tongue, and fingers disappear into the background so the song can speak.

| Pattern | Typical Notes | Practice Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Opening phrase | C – D – E – F (example in F major) | Play slowly with a tuner to center pitch on each note before adding rhythm. |

| Repeated notes | G – G – G, A – A – A | Experiment with light tongue strokes near the tip of the reed for clarity. |

| Small skips | E to G, F to A | Keep fingers close to the keys to avoid extra motion or unwanted noise. |

A Simple Practice Routine To Keep The Song Alive

You do not need an hour to make this tune meaningful. A short, focused routine with your clarinet fingering chart nearby can change the way it feels under your fingers.

| Step | Time | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Slow reading with chart | 2-3 minutes | Match each written note to its fingering, no rhythm pressure. |

| 2. Steady tempo | 3-4 minutes | Use a metronome, keep tone warm from mouthpiece to bell. |

| 3. Expression passes | 3-4 minutes | Add dynamics, soft verse then loud verse, like a short story. |

| 4. Creative variation | 2-3 minutes | Try small ornaments, slight rubato, or a swing feel. |

- Play the melody once exactly as written on the chart.

- Repeat it at a softer dynamic, almost whispering into the mouthpiece.

- Play it louder, imagining a full band behind you.

- Finally, close your eyes and let phrasing and breath lead the fingers.

For related clarinet journeys, you might enjoy reading about historical Bb clarinet makers on Martin Freres, learning how simple folk-like lines connect to classical solos in the Mozart clarinet works, or exploring how wind band traditions grew around clarinet sections in community ensembles.

Key Takeaways

- Use the “I've Been Working On the Railroad” clarinet fingering chart as a bridge between basic notes and expressive phrasing.

- Treat this folk song with the same care you would bring to Mozart, Brahms, or a jazz standard to build your musical voice.

- Keep practice short and focused: slow reading, steady tempo, expressive passes, and creative variations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is I've Been Working On the Railroad clarinet fingering chart?

The “I've Been Working On the Railroad” clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide that shows every note and matching fingering needed to play the tune on Bb clarinet. It helps beginners and returning players move confidently between pitches so they can focus on tone, rhythm, and musical expression.

Is I've Been Working On the Railroad good for beginner clarinetists?

Yes. The melody usually stays in a comfortable range, often between written low C and A in the staff. That friendly contour lets beginners practice steady air, simple finger patterns, and basic articulation while playing a familiar song that friends and family recognize instantly.

Which clarinet register does this song mainly use?

Most classroom arrangements sit mostly in the chalumeau and lower clarion registers. You will likely play notes like low E, F, G, A, and B natural, with only a few steps into the upper part of the staff. This keeps embouchure adjustments gentle while you build control and consistent tone.

How often should I practice this tune with the fingering chart?

Short, frequent sessions work best. Five to ten minutes a day is enough to memorize the fingerings and start shaping expression. Use the chart at first, then gradually look away and trust your hands and ears. Return to the chart whenever a note feels uncertain or out of tune.

Can advanced players still benefit from this simple song?

Absolutely. Advanced players can use the tune as a tone, phrasing, and creativity study. Try long-tone variations, dynamic extremes, jazz-style embellishments, or klezmer-like inflections. Treat each phrase with the same care you would in Brahms or Copland, and the song becomes a compact artistry workout.