If there is one tune that can turn a Bb clarinet into a singing, shouting, second-line parade partner, it is “When the Saints Go Marching In.” You do not just play this song, you join a long, dancing line of clarinetists who used it to cry, laugh, praise, and groove through an entire century of music.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

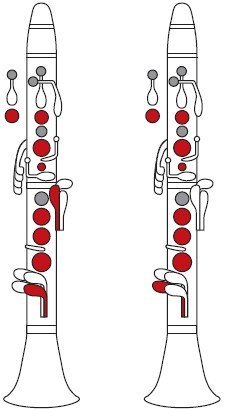

The When the Saints Go Marching In clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide to the exact notes and fingerings needed to play this classic melody in B? clarinet keys. It helps beginners and advancing players learn the tune faster, play in tune, and join bands and ensembles with confidence.

The story behind “When the Saints” on clarinet

Long before it found its way into school bands and clarinet method books, “When the Saints Go Marching In” was a spiritual sung in churches and gathering halls in New Orleans. It carried hope, grief, and a promise that something brighter waited just beyond the horizon. When clarinetists picked it up, they gave that melody a reed, a column of air, and a voice that could wail straight through a brass band.

New Orleans bandleader Louis Armstrong made “When the Saints” famous worldwide, but listen carefully to those old recordings and you will hear the clarinet gliding around the trumpet line, filling the space between melody and rhythm. Players in groups like the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band used clarinet to twist and bend the tune into something half prayer, half party.

From there, the song traveled. It moved from the streets of New Orleans to concert halls, from second-line parades to conservatory juries. Today, a young Bb clarinetist in a school band might learn “When the Saints Go Marching In” in the same week that a jazz student studies Sidney Bechet's soprano sax phrasing or Benny Goodman's swing recordings. The tune is a bridge between all of them.

Clarinet legends who brought “When the Saints” to life

Clarinet history is full of players who could make a single simple tune sound like an entire autobiography, and “When the Saints Go Marching In” is one of their favorite playgrounds.

In early jazz, the line between clarinet and voice is very thin. Johnny Dodds, who played with Louis Armstrong and Kid Ory, often used hymns, spirituals, and parade songs as a base for improvisation. His woody sound and flexible embouchure made the clarinet float above trombone and cornet, and you can hear that same church-born lift in performances of “When the Saints” by later clarinetists.

Benny Goodman did not record “When the Saints” as often as many traditional jazz bands, but his approach to swing phrasing helps unlock the tune. His famous recording of “Sing, Sing, Sing” with Gene Krupa shows how a clarinet can cut through a big band using the same type of bold articulation and air support you need in a bright, marching version of “When the Saints.” Artie Shaw's warm, fluid legato offers another model for stretching the melody into longer, singing phrases.

Buddy DeFranco brought bebop language to clarinet, and when you hear him play tunes like “Donna Lee” or “Cherokee,” you can almost imagine what his lines would sound like over the chord changes often used to reharmonize “When the Saints Go Marching In” in modern jazz arrangements. His work connects the simple hymn roots to the fast, chromatic language of players like Charlie Parker.

In klezmer, Giora Feidman and David Krakauer have both taken spiritual and folk melodies and blown them wide open with pitch bends, scoops, and raw, vocal phrasing. When a clarinetist uses those same expressive techniques in “When the Saints,” the tune stops sounding like a band exercise and starts sounding like a human voice in conversation with a congregation.

On the classical side, players like Sabine Meyer, Martin Frost, and Richard Stoltzman sometimes bring spirituals and folk tunes into recital encores and crossover projects. Stoltzman's recordings of American songs show how a classically trained embouchure and controlled vibrato can give a simple melody an almost choral depth. If you apply that kind of breath control and dynamic shaping to “When the Saints,” the piece turns into a miniature aria.

Iconic recordings and arrangements that shape how clarinetists hear this tune

The way you play “When the Saints Go Marching In” on Bb clarinet is colored by the versions that already live in your ears. There are hundreds, but a handful have shaped how clarinetists think, tongue, and breathe this melody.

Louis Armstrong's 1938 Decca recording is still the reference point. While the main horn is trumpet, listen to the reed section and clarinet fills. The short, swinging accents over the snare drum and tuba create a lesson in offbeat emphasis for any clarinetist. Those little fills are like tiny clarinet etudes in syncopation.

British trad jazz bands, such as Chris Barber's groups with clarinetists like Monty Sunshine, recorded versions where the clarinet takes more of a front-line role. Here, the melody often passes between trumpet, trombone, and clarinet, which teaches you how to project the tune while still blending with brass and banjo.

New Orleans clarinetists like Pete Fountain brought a smoother, almost crooning sound to “When the Saints.” His version on albums like “The Best of Pete Fountain” combines traditional New Orleans swing with a relaxed vibrato and rich throat-tone focus. For Bb clarinet students wrestling with the break between A and B natural, this style offers a beautiful model of how to keep that area singing.

In classical and concert band settings, arrangers such as James Swearingen and Robert W. Smith use “When the Saints Go Marching In” in young band scores where clarinet carries the main tune. Here, articulation marks, dynamics over 8, 12, or 16-bar phrases, and unison clarinet scoring turn the piece into a shared lesson in breath support and blend for the whole section.

Most band and jazz arrangements of “When the Saints Go Marching In” group the melody into 4 or 8-bar phrases. Clarinetists can use this to plan breaths, crescendos, and vibrato, turning a simple tune into a clear phrasing study.

Modern crossover clarinetists sometimes quote “When the Saints” in unexpected places. In jazz festival jam sessions, a player might slip a bar or two of the melody into a solo on “All of Me” or “When the Saints” might appear briefly in a clarinet choir transcription as a hidden inner voice. Hearing those tiny cameos trains your musical ear to recognize the tune in any key and respond creatively.

From spiritual to second-line standard: a brief journey

The roots of “When the Saints Go Marching In” lie in 19th-century spirituals and hymns. These songs were passed from voice to voice long before they reached notation paper. When brass bands in New Orleans began mixing church repertoire with street parade music, clarinet slid naturally into the band as the agile melodic voice between cornet and trombone.

In early 20th-century marching bands, the clarinet part often sat in the middle of the harmony stack, weaving arpeggios and scale runs around the main tune. Over time, as jazz developed, the clarinet escaped that middle role and took on the melody itself, especially in small combos. “When the Saints” was perfect for this because its structure is clear: short phrases, strong chord tones, and a rhythm that can shift from straight march to swinging two-feel without breaking.

During the swing era, big bands brought the song into large ensembles. Clarinetists influenced by players like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw started to phrase the tune with more chromatic approach notes and swing eighth notes. Even if the original harmony stayed simple, the clarinet lines grew more adventurous.

By the time of bebop and post-bop, “When the Saints Go Marching In” sometimes disappeared from the main stage but stayed alive in New Orleans traditional jazz, street parades, and school bands. Clarinet teachers used it to introduce jazz phrasing to students who were also working on Weber concertos and the Mozart Concerto in A major. The tune turned into a connecting thread between sacred song, street celebration, and formal training.

Today, you might hear a Bb clarinetist play “When the Saints” in a concert band in Tokyo, a jazz club in Berlin, or a brass band festival in New Orleans. The fingerings, reeds, and mouthpieces may be modern, but the emotional message is the same as the early vocal versions: movement, hope, and a feeling that something joyful is just around the next corner.

Why “When the Saints” hits the heart so quickly

On paper, the melody of “When the Saints Go Marching In” looks almost too simple. A few notes in the home key, clear rhythms, easy intervals. But the moment you put it on a Bb clarinet, something happens. The song invites color.

The clarinet can shape a single note in so many ways: a breathy low chalumeau G, a round middle C, a ringing clarion E. When you play “Oh when the saints” on clarinet, each of those syllables can get its own dynamic curve, its own hint of vibrato, its own small swell of air. That freedom is what makes the song so addictive to play.

The tune also carries a deep mix of moods. It can sound like a funeral march in the first chorus and then erupt into a celebration in the next. New Orleans brass bands often start “When the Saints” slowly in a dirge tempo, then flip into a dancing, up-tempo groove. Clarinetists ride that change using accents, growls, glissandi, and brighter tone color above the staff.

On a personal level, many players remember “When the Saints Go Marching In” as one of the first songs they played that sounded like real music, not just exercises. The moment a clarinetist can join a band, stand in front of a crowd, and let that melody ring out, the instrument stops being a puzzle of keys and becomes a way to speak.

What mastering this tune gives you as a clarinetist

Spending time with this free clarinet fingering chart for “When the Saints Go Marching In” does more than teach you one song. It wires in a whole set of musical habits.

You strengthen your sense of key center. In many band arrangements, “When the Saints” sits in concert B?, which means clarinets read in C major. That is the same key you use in many early etudes and pieces, from simple duets to easy versions of Mozart themes. Every note you play in “When the Saints” builds muscle memory for all of that repertoire.

You also learn phrasing and air control in a friendly setting. Each phrase is short enough that a developing player can make it through on a single breath, but long enough to practice a smooth crescendo or a shaped decrescendo into the cadence. That is the same skill you need in lyrical passages in Brahms' Clarinet Sonata in F minor or the slow movement of the Weber Concertino.

For jazz or improvisation students, “When the Saints Go Marching In” is a blank canvas. Once the melody is secure, you can begin to vary rhythms, add grace notes, or outline the chords with arpeggios. Clarinetists who love players like Artie Shaw or Buddy DeFranco can treat the chart as home base, then gradually stretch beyond the notes on the page.

A few practical notes on the fingering chart

The Bb clarinet fingering chart for “When the Saints Go Marching In” keeps the melody mostly in the comfortable range around low G up to middle C and D, occasionally stepping over the break. That is intentional: it lets beginning and returning players focus on beautiful sound, accurate rhythm, and expressive phrasing instead of wrestling with extreme altissimo notes.

When you look at the chart, notice where fingerings repeat. The tune uses recurring patterns, such as stepwise motion between A, B, and C, and leaps from tonic to dominant. Once your right-hand position and left-hand thumb are stable, those patterns start to feel like familiar dance steps. With each repetition, you can shift more and more attention to tone color and style.

| Section of the tune | Typical range on Bb clarinet | Feeling to focus on |

|---|---|---|

| Opening phrase | G below the staff to C in the staff | Clear, vocal tone and confident rhythm |

| Middle response phrases | A to D in the staff | Call-and-response, like a conversation |

| Final “when the saints” tag | G up to E or F, depending on version | Building excitement and a strong cadence |

Simple practice ideas to make your chart sing

You already have the free clarinet fingering chart. Now think of your practice time as a short rehearsal with a friendly New Orleans band or a university wind ensemble. A few focused minutes can transform the way this melody feels under your fingers.

| Practice focus | Time | How often |

|---|---|---|

| Slow melody with tuner and metronome | 5 minutes | 3 times per week |

| Phrase shaping and dynamics only | 5 minutes | 2 times per week |

| Swing or march style experiment | 5 minutes | 2 times per week |

| Play-through with backing track or piano | 5 minutes | 1 time per week |

As you grow more comfortable, try pairing “When the Saints Go Marching In” with other tunes from the same key and range. On MartinFreres.net you can connect it to pieces that use similar note patterns and clarinet fingerings, such as beginner-friendly patriotic melodies, folk tunes, or simple jazz standards. That way, every bit of work on this chart carries over to new music.

- Play the entire melody from the chart at a slow, steady tempo.

- Repeat, but this time add one dynamic choice per phrase, such as a small crescendo into the final note.

- Play again in a lighter, more swinging style, keeping the fingerings identical.

- Finish by closing your eyes for one chorus and imagining a brass band marching with you.

Key Takeaways

- Use the free When the Saints Go Marching In clarinet fingering chart to focus on tone, phrasing, and style, not just hitting the right notes.

- Listen to jazz, concert band, and crossover recordings so your Bb clarinet sound is shaped by real musical stories behind the tune.

- Treat this melody as a springboard: once it feels easy, use the same fingerings and phrasing ideas in other songs and improvisations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is When the Saints Go Marching In clarinet fingering chart?

The When the Saints Go Marching In clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide that shows every note and Bb clarinet fingering needed for the melody. It helps you see left-hand and right-hand positions at a glance so you can learn the tune quickly, play in tune, and focus on phrasing and style.

Is When the Saints Go Marching In suitable for beginner clarinet players?

Yes. The song mostly stays in a friendly range from low G to D or E in the staff, with simple rhythms and clear phrases. Beginners can use the chart to learn steady fingerings and air support, while more advanced clarinetists experiment with swing, dynamics, and improvised variations.

What key is When the Saints Go Marching In usually played in for Bb clarinet?

In many school band and jazz band arrangements, the concert key is B? major, so Bb clarinet parts are written in C major. Some traditional jazz groups choose other keys, but starting in C on the clarinet staff keeps the fingerings simple and matches most educational charts and recordings.

How can I make my clarinet version of When the Saints sound more like jazz?

Keep the written fingerings but adjust articulation and rhythm. Use light tonguing, slightly uneven swing eighth notes, and a bit of dynamic contrast. Listening to clarinetists such as Pete Fountain and Benny Goodman will give you ideas for accent placement, breath phrasing, and tone color.

How does this song help with other clarinet music?

The patterns in When the Saints Go Marching In, such as stepwise motion and tonic-dominant leaps, appear in many band pieces and solos. Practicing this tune improves your hand position, embouchure stability, and sense of phrase, which later supports works by composers like Mozart, Weber, and Brahms.