If you have ever heard a clarinet glide upward like a dream staircase in a Debussy prelude or spiral through a dizzying Dizzy Gillespie run, you have already met the D whole-tone scale. On Bb clarinet, the D whole-tone scale is like a secret door: one twist of the hand and suddenly gravity feels softer, harmony bends, and the air around your sound starts to shimmer.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The D whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet is a six-note scale built from D using only whole steps: D, E, F#, G#, A#, C. It creates a dreamy, floating sound that helps clarinetists improvise in jazz, color film music, and add modern sparkle to classical pieces.

The strange magic of the D whole-tone scale

The D whole-tone scale is built on equal steps: D, E, F#, G#, A#, C. No half steps, no friction, just this smooth, glassy series of tones. On clarinet it feels like sliding across ice with perfect balance. There is no single “home” note that begs to resolve, so your ear floats while your fingers sketch patterns.

Claude Debussy loved this sound. If you listen to “Prelude a l'apres-midi d'un faune” and sing a few of those woodwind phrases on your clarinet, you can almost hear the D whole-tone color hiding inside his harmony. Film composers picked up that same sound later: you hear it in scores by John Williams, Alexandre Desplat, and Joe Hisaishi, especially when the clarinet needs to sound like a memory or a mirage instead of a marching soldier.

The D whole-tone scale uses 6 distinct notes, each a whole step apart. This perfect symmetry removes normal tonal gravity, which is why it feels so ideal for dream scenes, magic, and jazzy tension.

Clarinet legends who lived in whole-tone colors

Whole-tone scales have teased clarinetists for over a century. They sit in orchestral parts, solo cadenzas, and wild jazz choruses. The D whole-tone scale in particular sits at a sweet spot on the Bb clarinet, where the chalumeau, throat tones, and clarion register all share the color.

Think of Sabine Meyer playing Debussy and Ravel with the Berlin Philharmonic. In Ravel's “Daphnis et Chloe” and “La Valse” the clarinet line often brushes against whole-tone harmonies. When she leans into a slightly misty, covered sound on notes like E and F# over a D pedal, you can hear the ghost of the D whole-tone scale peeking out of the texture.

Martin Frost takes the idea even further in contemporary pieces like Kalevi Aho's Clarinet Concerto and Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales”. He will rip through entire whole-tone runs from D to high C, using double-tonguing and circular breathing to keep the line hanging in midair. That sound, almost like a clarinet turned aurora borealis, owes a lot to whole-tone material.

In jazz, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw both treated whole-tone lines as a spice jar. Listen to Goodman's solos on “Sing, Sing, Sing” or “Stompin' at the Savoy” and you will hear whole-step runs that outline chords in ways that almost flatten into whole-tone colors. Buddy DeFranco, especially in his live recordings from the 1950s, uses explicit whole-tone runs around D to slide over dominant chords and create delicious suspense before dropping back into bebop language.

Klezmer clarinetists like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer sometimes brush against whole-tone fragments when they bend notes around dominant chords in freygish-style modes. In pieces like Krakauer's versions of “Der Heyser Bulgar” and “Moldavian Hora” you can hear quick flashes of D, E, F#, G# that feel like the scale is trying to break into the dance for a split second.

Where the D whole-tone scale hides in famous pieces

The beauty of the D whole-tone scale is that it often appears without being named. It sneaks through clarinet lines as a bridge between keys, a special effect, or a little flash of color.

In classical and impressionist music, you can listen for this scale in:

- Debussy's “Premiere Rhapsodie” for clarinet and piano, especially in the slow, swirling opening phrases and some of the ascending runs around high D and E.

- Ravel's Piano Concerto in G, where the clarinet weaves around whole-tone harmonies in the slow movement, floating above muted strings and delicate harp.

- Messiaen's “Quartet for the End of Time,” particularly “Abime des oiseaux”. While not written as a pure D whole-tone exercise, many of the soaring gestures cross through D, E, F#, G# patterns that give the solo its otherworldly glow.

In the romantic clarinet repertoire, Weber and Brahms did not write pure whole-tone scales as often, but their clarinet concertos and sonatas are full of dominant chords where a D whole-tone run fits perfectly in improvisation or cadenzas. Modern soloists like Martin Frost and Andreas Ottensamer sometimes add tasteful whole-tone embellishments in cadenzas to Weber's Clarinet Concerto No. 1 or Copland's Clarinet Concerto.

Jazz is where the D whole-tone scale really shows its teeth. Try listening for it in:

- Benny Goodman's live performances of “Rose Room” and “Flying Home”, where he briefly outlines whole-tone movement over V7 chords around D and G.

- Artie Shaw's solos on “Begin the Beguine” and “Concerto for Clarinet”. The big cadenza in the concerto has lines that nearly spell out D whole-tone scales while the band hovers on a dominant harmony.

- Buddy DeFranco's bebop recordings like “Opus One” and “Donna Lee” where he uses whole-tone flashes to slide between altered dominants and chromatic ii-V chains.

In film scores, look to the clarinet lines in:

- John Williams's “Harry Potter” scores, where the clarinet often floats above strings in Diagon Alley and Hogwarts scenes with runs that could easily be practiced as whole-tone patterns.

- Alexandre Desplat's “The Shape of Water” and “The Grand Budapest Hotel”, where clarinet glissandi and scale fragments near D and E give the music that blend of nostalgia and magic.

- Joe Hisaishi's music for Studio Ghibli films like “Spirited Away” and “Howl's Moving Castle”, where the clarinet occasionally paints clouds of sound using scales that touch the D whole-tone universe.

| Use of D Whole-Tone | Typical Setting | Clarinet Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Short run from D to C | Debussy-style orchestral color | Dreamy, suspended phrase ending |

| Full octave sweep | Jazz solo over a dominant chord | Tension and release into the next chorus |

| Broken arpeggio patterns | Film underscore for a magical scene | Shimmering, glass-like motion in the background |

From 19th century experiments to jazz clubs and studios

The whole-tone scale started to appear seriously in the late 19th century. Composers like Franz Liszt and Alexander Scriabin played with it on piano, but it was Debussy who really turned it into a language. He was fascinated by Javanese gamelan sounds he heard in Paris and tried to imitate that floating feeling with Western instruments.

Clarinetists in French orchestras at the time, like those in the Paris Opera and the Orchestre de la Societe des Concerts du Conservatoire, suddenly had to phrase melodies that did not “resolve” in the normal way. This forced a different kind of breath control and embouchure focus. Long tones over whole-tone harmonies, especially around notes like D and E, taught players to sing even when the harmony felt unresolved.

Into the 20th century, composers such as Olivier Messiaen and Igor Stravinsky used whole-tone fragments to break open tonality. In “The Rite of Spring” you hear wind lines that almost sound like proto-jazz whole-tone riffs. Clarinetists like Heinrich Geuser and later Karl Leister with the Berlin Philharmonic had to shape these scales with a modern, flexible chalumeau and clarion sound.

As jazz grew in New Orleans and New York, players borrowed the same six-note symmetry to spice up dominant chords. Sidney Bechet on soprano sax, and later Benny Goodman on clarinet, discovered that running up a whole-tone scale from D could take a plain G7 chord and make it sound exotic and dangerous. That sound moved into swing, then bebop with players such as Buddy DeFranco and Eddie Daniels, and then into more modern styles like those heard from Don Byron and Anat Cohen.

Today the D whole-tone scale is standard vocabulary in conservatories and jazz programs. Classical clarinet students practice it alongside major and minor scales for auditions, while improvisers use it in patterns over V7 chords. Film session players in London, Los Angeles, and Paris keep it ready for those days when the score calls for “air, mystery, and a little bit of trouble” in the clarinet part.

How the D whole-tone scale feels on Bb clarinet

On Bb clarinet, the D whole-tone scale feels like a staircase where every step is the same size, but each view from the landing is different. Start on low D with a warm chalumeau sound. As you climb to E, F#, and G#, the clarion register opens and the sound brightens without ever settling. By the time you reach A# and C, you are hanging in the air, waiting to choose your next color.

Emotionally, this scale often feels:

- Dreamy and floating, especially in slow legato phrases with plenty of air.

- Playful and slippery in quick staccato runs, like cartoon magic or mischief.

- Dangerous and edgy when played loudly over a dominant chord in a jazz solo.

Because the notes are all equally spaced, you can tilt the mood simply by changing dynamics, articulation, and vibrato. Whisper it pianissimo like Sabine Meyer in a Debussy passage, or blast it forte like Artie Shaw tearing through the cadenza of “Concerto for Clarinet” and it becomes a completely different character.

Why the D whole-tone scale matters for your playing

Practicing the D whole-tone scale does more than train your fingers. It reshapes your ear. You learn to hear chords as colors instead of rules, and suddenly pieces by Debussy, Ravel, and Messiaen feel less mysterious and more like friendly challenges.

For a jazz player, this scale is a direct gateway into altered dominant sounds. Over a G7 chord, the D whole-tone scale gives you the 5, 13, b7, b9, sharp 11, and natural 3. That is why Benny Goodman and Buddy DeFranco reached for it in their solos. It lets you sound sophisticated without memorizing twenty chord-scale names.

For classical players working on Mozart's Clarinet Concerto or Weber's Concertino, practicing D whole-tone runs builds evenness across breaks, throat tones, and clarion notes. When you later meet those slippery chromatic runs in Weber or the delicate long phrases in Copland's Clarinet Concerto, your fingers and your sound will already know how to float.

Even 5 focused minutes on the D whole-tone scale can improve your finger evenness, voicing between chalumeau and clarion, and confidence on tricky accidentals.

| Practice Focus | Time | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Slow D whole-tone long tones (slurred) | 2 minutes | Daily warm up |

| Medium tempo patterns (thirds, arpeggios) | 2 minutes | 3-4 times per week |

| Fast runs for jazz or cadenzas | 1 minute | Before improvisation sessions |

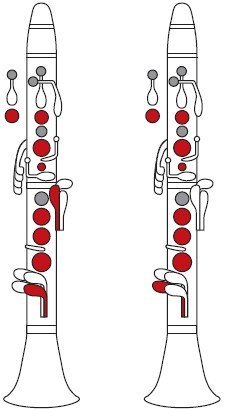

A quick, friendly note on Bb clarinet fingerings

You have the full fingering chart in front of you, so think of this as a short pep talk rather than a lesson. On Bb clarinet, the D whole-tone scale moves through D, E, F#, G#, A#, C and back to D. The chart shows standard Boehm-system fingerings for each register, including alternate pinky options for F# and C to smooth out fast passages.

As you run the scale, notice where the register key comes into play. Moving from throat A to clarion B and C using the register key cleanly will make entire patterns feel easy. Let your left-hand position stay relaxed over the tone holes, especially between E and F#, so your sound does not pinch. If your altissimo C feels tight, think “more air, less embouchure pressure” and keep the tongue light on the reed.

- Play the scale slowly from low D to high D, legato, reading from the chart.

- Repeat with staccato, keeping the tongue light and close to the reed.

- Add simple rhythms: triplets, swung eighths, and offbeat accents.

- Try one phrase from a favorite piece, and slip a D whole-tone run into it as an experiment.

Where to go next with this sound

Once the D whole-tone scale feels like a friend, it connects beautifully to other clarinet adventures. Practice it alongside your D major scale to feel the difference in tension, or pair it with a D blues scale for jazz choruses on standards like “All of Me” or “Autumn Leaves”.

On Martin Freres, you can deepen this work with related guides, such as free fingering charts for other scales, articles on smooth clarinet tone across the break, and stories from the Martin Freres clarinet history that inspire careful listening. Treat the D whole-tone material as part of your broader clarinet storytelling, not just as another line in a scale book.

Key Takeaways

- The D whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet creates a floating, dreamlike sound used by classical, jazz, and film composers.

- Practicing this scale sharpens your ear for color, strengthens technique across registers, and enriches improvisation.

- Use the free fingering chart as a map, then listen to masters like Meyer, Frost, Goodman, and DeFranco to shape your own voice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet D whole-tone scale fingering?

The Bb clarinet D whole-tone scale fingering is the pattern that produces D, E, F#, G#, A#, and C using standard Boehm-system fingerings across chalumeau and clarion registers. Practicing this pattern lets you move smoothly through the scale, so you can use it in classical passages, jazz solos, and film-style color effects with confidence.

How do I use the D whole-tone scale in jazz improvisation?

Use the D whole-tone scale over G7 or G7 alt chords to create tension before resolving to C major or C minor. Start with simple runs from D up to C, then add rhythmic variation and articulation changes. Listen to Buddy DeFranco and Eddie Daniels to hear how they turn whole-tone material into swinging clarinet lines.

Why does the D whole-tone scale sound so dreamy on clarinet?

The D whole-tone scale uses only whole steps, so there are no typical leading tones or strong half-step pulls. On clarinet, that symmetry creates a floating sensation, especially when played legato with steady air. Composers like Debussy and Ravel used this color to suggest fog, magic, or time standing still.

How long should I practice the D whole-tone scale each day?

Even 5 minutes a day can make a difference. Spend 2 minutes on slow, beautiful legato from low D to high D, 2 minutes on medium-tempo patterns, and 1 minute on faster runs. Blend this into your normal routine of long tones, major scales, and articulation studies for a balanced session.

Should beginners learn the D whole-tone scale or wait until later?

Beginners can absolutely start with short parts of the D whole-tone scale once they know basic notes up to A or B. Use it as a fun color, not a test, and keep it slow and musical. More advanced players can extend the scale across full registers and add it into etudes, improvisation, and orchestral excerpts.