If you have ever fallen in love with that shadowy, on-the-edge sound in a movie soundtrack or a modern jazz solo, you have already heard the spirit of the D Locrian scale on clarinet. It is the sound of a question mark held in the air, a color that never quite settles, and it fits the Bb clarinet like a late-night whisper.

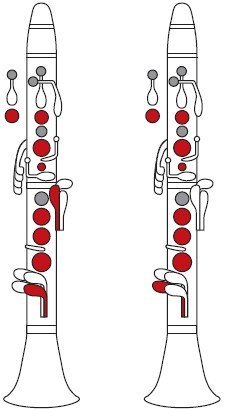

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The D Locrian scale on Bb clarinet is an 8-note mode built from D to D using the notes of E flat major. It features a dark, unstable sound with flattened 2nd and 5th degrees that sharpen your ear for tension, ear training, and expressive improvisation.

The D Locrian scale: mood, story, and a clarinetist's secret color

The D Locrian scale sits on that delicious fault line between beauty and danger. On a Bb clarinet, those notes speak with a slightly smoky tone, especially as you lean into the low register with the left-hand pinky keys and throat tones. It feels like walking down a quiet street just after midnight, streetlights flickering, bell keys gently clacking under your fingers.

Locrian has always been the odd child among the church modes. While D Dorian and D Phrygian have found their way into folk songs and classical themes, D Locrian is the restless cousin that composers reach for when they want unease. Clarinetists, with our blend of warmth and bite, can paint that unease with real color: soft subtone around low D, airy crescendos up to A and B flat, and that tense climb back to the top D that never quite resolves.

The flattened 2nd (E flat) and flattened 5th (A flat) are the heart of the D Locrian sound. Hearing and shaping these on Bb clarinet strengthens your intonation, ear training, and control of dark, unstable harmony.

From ancient modes to modern scores: how D Locrian found its voice

Locrian was mentioned in early modal theory, but almost never used as a full tonic scale in baroque or classical music. Composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, and Georg Philipp Telemann loved D minor and D Dorian for oboe and violin, yet they treated the Locrian collection as a passing color rather than home base. Still, the idea of a flattened 5th was already sneaking into harmony, long before jazz players named it.

Clarinet pioneers like Anton Stadler, who worked with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, did not write “D Locrian” over their parts, but they often brushed that color in passing. In the Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A major, tiny chromatic neighbor tones give a whiff of Locrian-style tension before sliding back to safer ground. Heinrich Baermann, muse to Carl Maria von Weber, lived in a sound world where that tritone was already becoming a dramatic tool.

In the late romantic era, composers such as Gustav Mahler and Claude Debussy started flirting with modes more openly. Clarinet lines in Mahler symphonies sometimes glance off Locrian shades on notes like B flat or A flat against D or E flat harmonies. Debussy's orchestral writing for clarinet in “La Mer” and “Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune” uses altered dominant colors that share Locrian DNA, giving clarinetists a taste of that suspended, unstable feeling.

By the 20th century, with Bela Bartok, Igor Stravinsky, and later Olivier Messiaen, modes were fully in the spotlight. Clarinet passages in Bartok's “Contrasts” and Stravinsky's “Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo” are packed with chromatic twists that feel almost Locrian when you land on that flattened 5th. Even when the score does not spell out “D Locrian,” your ear and fingers will recognize that dark tension as you move through low D, E flat, and A flat.

How great clarinetists touched the D Locrian sound

Very few players announce “Here is my D Locrian scale” on stage, but many have used its color in unforgettable ways. Listening for that flattened 2nd and 5th can change how you hear the legends.

Sabine Meyer, with her singing sound and precise control of the clarinet's throat tones and upper register, often reveals Locrian flavors in modern concertos. In Jorg Widmann's clarinet works, for instance, sudden clashes between D, E flat, and A flat leap out of the line. Meyer's recording of Widmann's music turns those notes into characters in a story, not just accidentals scattered across the staff.

Martin Frost has a talent for balancing mischief and menace in contemporary pieces. Listen to him in Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales” or his performances of Kalevi Aho's clarinet concerto. The way he leans into raised and lowered notes above a D pedal point sometimes feels like an extended meditation on D Locrian. You can almost hear the flattened 5th ring through his bell as he shapes those wide interval leaps.

Richard Stoltzman, with his jazz-influenced phrasing and flexible vibrato, often glides through Locrian-flavored licks in his arrangements of Gershwin and his collaborations with jazz rhythm sections. A quick lick spiraling around D, E flat, and A flat over a dominant chord is pure Locrian energy, even if it lasts only two beats. His control of the reed tip and mouthpiece allows him to turn those dissonances into sighs rather than stabs.

On the jazz side, think about Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw. Their big band charts, especially in more adventurous arrangements, play with altered chords where the clarinet rides the edge of Locrian land. Check Goodman on tunes with sharp, modern arrangements by Eddie Sauter: when the solo clarinet outlines a D half-diminished arpeggio (D, F, A flat, C), that is the skeleton of D Locrian speaking through a 1930s mouthpiece and ligature.

Buddy DeFranco, a bridge between swing and bebop, turned Locrian theory into everyday language. Over a C minor ii-V progression (D half-diminished to G7), he often traces lines that all but spell out D Locrian: D, E flat, F, G flat, A flat, B flat, C, D. If you transcribe his solos and play them on your Bb clarinet slowly, you will hear the scale hiding in plain sight under your fingertips.

In klezmer, clarinetists like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer do not usually label their modes with classical names, but listen to the raw edge of their pitch around D in freygish and altered minor modes. Slides between E flat and F, scoops into A flat, and snarling grace notes around the throat A and B flat bring out the same unstable core that gives Locrian its haunted quality.

Pieces and recordings where D Locrian leaves fingerprints

You will rarely see “D Locrian” printed at the top of a clarinet part, but its sound echoes in many famous works. Think of it as a ghost harmony that composers and improvisers keep summoning when they want trouble in the air.

In film scores, where clarinet often carries secretive or anxious lines, you can hear Locrian colors clearly. Consider the clarinet writing in John Williams's darker passages for “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” or “Minority Report.” There are moments where the clarinet holds a low D under shifting chords with E flat and A flat above, capturing that Locrian tension as the story tightens.

In Howard Shore's music for “The Lord of the Rings,” listen to the more ominous Shire or Mordor-related textures. English horn and clarinet sometimes weave lines that graze the D, E flat, and A flat combination. Even if the final harmony drifts elsewhere, the temporary color is pure Locrian unease.

On the concert stage, contemporary composers use D Locrian more overtly. Krzysztof Penderecki, in works like his clarinet quartet writing and chamber pieces, builds clusters where clarinetists sit uncomfortably on Locrian-type collections. The motion from low D to A flat in the chalumeau register, with the right-hand ring and pinky fingers working hard, creates a distinctive, almost vocal wail.

In jazz recordings, you can follow the D Locrian sound anywhere a ii half-diminished chord appears in C minor. Listen to modern clarinetists like Eddie Daniels or Anat Cohen when they improvise over minor standards. Over a D half-diminished to G7 progression, they often sketch lines packed with E flat and A flat tension against the D, especially using syncopated accents and altissimo notes like high A and B flat for extra heat.

Even in classical cornerstones, tiny Locrian moments flicker. In Brahms's Clarinet Quintet, there are passages in the slow movement where the harmony momentarily offers a D with an A flat or E flat in the surrounding strings. The clarinet part, often played by artists like Karl Leister or Sharon Kam, floats through these harmonies, and if you isolate those bars, they feel like fragments of D Locrian that never quite settle.

| Piece / Context | Where D Locrian Appears | Listening Focus for Clarinetists |

|---|---|---|

| Jazz ii-V in C minor | D half-diminished chord | Lines using D, E flat, A flat, B flat as tension notes |

| Modern concerto (Widmann, Aho) | Chromatic clusters around D | Trills and runs that highlight flattened 2nd and 5th |

| Dark film cues (Williams, Shore) | D pedal with E flat / A flat above | Long notes in the chalumeau register colored by dissonant harmony |

How D Locrian feels under your fingers and in your heart

Play a plain D major scale on your Bb clarinet, and it feels like opening a window on a bright morning. Then play the D Locrian scale from D to D using the notes of E flat major: D, E flat, F, G flat, A flat, B flat, C, D. Suddenly, that same D turns jittery, as if the floor has shifted a few centimeters sideways.

The flattened 2nd (E flat) has a special bite against D. On clarinet, especially around the throat E flat and the E flat made with side keys, that interval sounds like a warning. The flattened 5th (A flat) is even more unsettling. In the chalumeau register, with the right-hand fingers and low F/C key involved, the A flat above D feels like a cracked bell: rich, but never entirely safe.

This is why many players quietly fall in love with D Locrian as a practice color. It teaches you to savor dissonance, to hold tension without rushing to fix it. It pushes you to control every part of your setup: reed strength, embouchure pressure on the mouthpiece, airflow through the barrel and upper joint, the angle of your right-hand fingers as they seal the tone holes.

Expressively, D Locrian is perfect for:

- Whispered, suspenseful lines in improvisation

- Dark, floating introductions before a brighter key

- Inner voices in chamber music that sound haunted but soft

- Soundtrack-style improvisations over drones or piano clusters

Why this scale matters for you as a clarinetist

Even if you never say the word “Locrian” out loud in rehearsal, the D Locrian scale strengthens skills you use every day. Playing it cleanly demands accurate half-hole work on notes like G flat, solid coverage with your right-hand ring finger on A flat, and precise voicing as you cross the break between throat tones and clarion register.

For students, it is a powerful ear training tool. If you can hear the difference between D minor, D Dorian, and D Locrian, your intonation within a clarinet section will tighten dramatically. You will recognize altered chords in your band or orchestra scores more quickly, tapping into that same listening awareness that legends like Sabine Meyer and Martin Frost bring to modern scores.

For improvisers, D Locrian is your faithful companion over D half-diminished chords and over many filmic textures created on piano or synthesizer pads. Practicing it turns your fingers into storytellers who know how to hover in suspense instead of sprinting straight to resolution.

For advanced players, D Locrian practice can be a daily meditation. Long tones on low D, E flat, and A flat, shaped with dynamic swells and subtle vibrato, sharpen your breath support and tonal shading. It is like holding a note in a Mahler symphony or a Shostakovich chamber piece, waiting for the harmony to shift under you.

Quick D Locrian practice ideas for Bb clarinet

You have the fingering chart, so there is no need for a long technical manual. Instead, here are some simple ways to bring the D Locrian scale to life on your Bb clarinet.

- Sing it, then play it: Sing D to D in the D Locrian pattern (using E flat major notes), then match that contour on your clarinet using the chart. This connects your ear to your fingers.

- Long-tone staircase: Hold each note of the scale from low D upward for 8 slow counts, focusing on smooth air through your mouthpiece, barrel, and upper joint.

- Broken thirds: Play D-F, E flat-G flat, F-A flat, and so on. This highlights the dissonant intervals that give Locrian its color.

- Drone play: Use a piano or tuner drone on D or E flat and improvise small phrases using only the D Locrian scale.

| Practice Focus | Time per Day | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Slow scale up and down | 5 minutes | Finger coordination and tone consistency across registers |

| Broken intervals and arpeggios | 5 minutes | Comfort with dissonant leaps and half-diminished shapes |

| Improvisation over a D drone | 5 minutes | Develops phrasing, dynamic control, and modal storytelling |

A few practical fingering notes from the chart

The free clarinet fingering chart for the D Locrian scale shows every note you need, but a couple of spots deserve a friendly heads-up. The low D involves full right-hand coverage along with the left-hand pinky D key on the lower joint, so take time to relax your right wrist to keep the tone solid.

G flat and A flat can feel like speed bumps. For G flat, pay attention to how firmly your left-hand ring finger seals the tone hole; for A flat, many players prefer the right-hand side key option before the break and the standard A flat/A key combination above the break. Use the chart to compare these options in context.

| Note | Common Fingering Choice | Clarinetist Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Low D | Full left and right hand + low D key | Keep your right-hand fingers curved to prevent leaks |

| G flat | Standard left-hand ring finger | Check for even tone when slurring from F and to A flat |

| A flat | Side key or standard A flat/A combination | Experiment and choose the smoothest option for your hand |

If you enjoy this kind of scale storytelling, you might also like reading about the emotional warmth of the Bb clarinet G major scale fingering, the stormy character of the Bb clarinet D minor scale fingering, or the bright shimmer of the Bb clarinet A major scale fingering.

Key Takeaways

- The D Locrian scale on Bb clarinet is a dark, suspenseful color built from D using the notes of E flat major.

- Great clarinetists across classical, jazz, and klezmer traditions use D Locrian sounds in modern concertos, film scores, and improvisation.

- Practicing D Locrian strengthens your ear, your control of tension, and your ability to tell deeper musical stories on clarinet.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet D Locrian scale fingering?

The Bb clarinet D Locrian scale fingering follows the notes D, E flat, F, G flat, A flat, B flat, C, D. You use standard fingerings from the E flat major scale but start and finish on D. Practicing this pattern helps you handle half-diminished chords, dark film-style harmony, and advanced modal improvisation.

How is D Locrian different from D minor on clarinet?

D Locrian has a flattened 2nd and 5th (E flat and A flat) compared to D natural minor. On Bb clarinet, that gives the scale a more unstable, edgy sound. While D minor feels sorrowful but grounded, D Locrian feels suspenseful, almost unfinished, which is perfect for modern music and jazz.

Why should a beginner practice the D Locrian scale?

Even beginners benefit from D Locrian because it teaches careful listening. Moving between D, E flat, and A flat trains your ear for dissonance, and your fingers for tricky combinations like G flat and A flat. Short, slow practice on this scale builds confidence for later pieces with altered notes and complex harmony.

Which chords use the D Locrian scale in jazz?

In jazz, D Locrian is most often used over a D half-diminished chord in a ii-V-i progression in C minor. If you see a symbol like Dm7b5 leading to G7 and then C minor, your D Locrian scale fits perfectly over that first chord, giving you expressive tension before the resolution.

How can I make D Locrian sound musical, not like an exercise?

Try adding dynamics and phrasing. Use crescendos into the notes E flat and A flat, use gentle vibrato on long tones, and create small motifs instead of straight runs. Listening to players like Martin Frost or Buddy DeFranco can give you ideas on how to turn scale shapes into real musical sentences.