If the major scale is daylight on the clarinet, the B Locrian scale is that strange blue hour just before sunrise, when shapes are still shadows and every sound feels a little haunted. It is the mode that never quite settles, the one composers and improvisers reach for when they want tension, danger, or mystery that refuses to resolve.

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The B Locrian scale on Bb clarinet is a seven note mode built on the seventh degree of C major that sounds as C Locrian in concert pitch. It emphasizes dark, unstable intervals and sharp dissonances, helping clarinetists develop control, expressive color, and advanced ear training.

The sound story of the B Locrian scale

On a Bb clarinet, the B Locrian scale lives like a whispered rumor inside your regular C major fingerings. Same notes, different center. What changes is not the keys under your fingers, but the gravity pulling on your ear. Suddenly that B feels like “home” even though the harmony keeps slipping from under your feet.

Think of the half step from B to C, the tritone from B to F, and the fragile fifth that has been flattened into something unstable. This is the same unstable color that makes Dmitri Shostakovich sound restless, and why a John Williams film cue can make you grip the edge of your seat before anything actually happens on screen.

Clarinetists like Sabine Meyer, with her glassy upper register and laser focus on intonation, or Martin Frost, who stretches dissonance like taffy in pieces by Anders Hillborg and Magnus Lindberg, live inside this kind of uneasy color all the time. Locrian is that color in its purest, rawest form.

Clarinet players who secretly lived in this dark corner

Very few clarinetists walk on stage and announce, “Now I will play the B Locrian scale.” But listen closely to their lines, and it is hiding there, especially in the way they treat the seventh degree of a key and that infamous tritone.

Anton Stadler, Mozart's clarinet muse, may never have used the word “Locrian,” but the Clarinet Concerto in A major, K. 622 is full of moments where the orchestra leans into dissonant leading tones and flattened fifths before letting the clarinet float above it. On an extended basset clarinet, Stadler toyed with shadowy low notes around B and C, brushing against Locrian colors before melting back into the safety of major and minor.

Heinrich Baermann, Weber's virtuoso, pushed these tensions even more directly. In Carl Maria von Weber's Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, those fiercely chromatic runs and snarling diminished chords often treat the leading note as a pivot point. Shift your ears for a moment and you can hear Locrian patterns tracing through arpeggios and passing tones, especially in the first movement cadenza when the clarinet dances around F and B.

Fast forward to the twentieth century and you hear Richard Stoltzman flirting with Locrian-like gestures in his recordings of Olivier Messiaen‘s Quartet for the End of Time. The movement Abime des oiseaux is a masterclass in suspended dissonance: pianissimo high notes, wide leaps across the break, and that sense that the floor could fall out at any moment. Nothing screams “B Locrian,” yet the same unstable intervals that define Locrian are there, painted across time and silence.

In jazz, the connection is even clearer. Buddy DeFranco, a pioneer of bebop clarinet, leaned hard into diminished arpeggios and altered dominant chords in his solos with the Oscar Peterson Trio. Those same diminished shapes line up perfectly with Locrian note choices. Listen to DeFranco's solos on standards like I'll Remember April and notice the moments where he slides through scales that could almost be labeled Locrian on certain chords.

Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw might not have diagrammed modes in a practice notebook, but their handling of tense turnarounds, particularly in pieces like Goodman's “Sing, Sing, Sing” or Shaw's “Nightmare,” draws on the same pool of notes: flattened fifths, half step clashes, and dark chromatic passing tones.

Then there are artists like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer, who turned klezmer clarinet into a kind of improvised prayer. In traditional tunes like “Der Heyser Bulgar” or Krakauer's fiery recordings with the Klezmatics, the clarinet often hovers on notes that feel like a suspended leading tone, with a flattened fifth itching underneath. It is not classical Locrian, but the emotional DNA is similar: unresolved, questioning, just a bit dangerous.

Iconic pieces where Locrian colors bleed through

If you look for a piece titled “B Locrian Rhapsody,” you will probably come up empty. But the flavor of this mode quietly inhabits some of the most gripping clarinet writing you can play or hear.

In the orchestral world, listen to Igor Stravinsky‘s The Rite of Spring. The famous opening bassoon solo is often discussed as a modal, ancient chant. Later in the piece, when the clarinet section of orchestras like the Berlin Philharmonic or the Chicago Symphony Orchestra digs into biting clusters and crunchy woodwind chords, the half steps and tritones feel straight out of Locrian practice.

Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5 and Symphony No. 10 both use clarinet soli that lean across flattened fifths and sharpened leading tones. Look at the second movement of the Fifth, play the line slowly, and you will find patterns that sit exactly like fragments of a Locrian scale transposed to different roots.

In solo and chamber music, Brahms‘ Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 has passages where the clarinet hovers around F and B in a way that makes the diminished fifth glow. Recordings by Sabine Meyer with the Berlin Philharmonic Octet, or Karl Leister with the Amadeus Quartet, show just how much color can be squeezed out of that fragile interval.

For contemporary clarinet, check out John Adams‘ Gnarly Buttons. In recordings by Michael Collins and Martin Frost, the clarinet winds through spiky, mode-shifting lines over pulsing harmonies. There are stretches where the pitch set is effectively Locrian on various roots, including B, creating that nervous, twitchy energy Adams is famous for.

Film composers love this same pool of notes. While written scores may not label a passage “B Locrian,” the sound is unmistakable. In Hans Zimmer‘s darker cues, or in Alexandre Desplat‘s shadowy clarinet writing for films like The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Shape of Water, the clarinet sneaks around half steps and diminished fifths to create suspense. Practice your B Locrian scale slowly, and suddenly those lines feel familiar under your fingers.

The B Locrian scale on Bb clarinet uses the same seven notes as C major, but with B as the tonal center. The half steps (B to C and E to F) and the flattened fifth (B to F) train your ear and embouchure to handle intense dissonance with control.

From medieval mode to modern clarinet practice

The Locrian mode has ancient roots. Early theorists classified it as one of the church modes, but performers quietly ignored it because it lacked a stable perfect fifth. In other words, it sounded too unstable for the harmony of its time. Organists, singers, and viol players treated it more like a curiosity than a daily tool.

The clarinet did not even exist yet, but the idea of this unstable mode sat waiting. Once the clarinet matured in the 18th century, with makers like Johann Christoph Denner and later Martin Freres refining the bore, keys, and mouthpiece, composers suddenly had an instrument that could whisper, scream, and slide across dissonant intervals with uncanny agility.

By the romantic era, when Weber and Brahms were stretching harmony with diminished chords and modal flavors, Locrian colors slipped into clarinet writing as expressive spice. They rarely called it Locrian, but the sound was there, especially in slow introductions, transitions, and the ghostly corners of development sections.

In the twentieth century, with the rise of jazz and modernism, modes became practical playgrounds. Saxophonists and trumpeters began practicing Locrian patterns for improvising over half diminished chords. Clarinetists like Artie Shaw and Buddy DeFranco absorbed the same vocabulary. Even if they labeled it “half diminished scale” or just “that tense run over the ii chord,” they were essentially practicing Locrian shapes.

By the time you reach contemporary soloists like Sharon Kam, Jorg Widmann, or Andreas Ottensamer, the language of modes is simply part of the craft. Whether in Widmann's own works for clarinet and ensemble, or in edgy new pieces premiered by Kam, those edgy, dissonant scales show up as a natural extension of the clarinet's voice.

How B Locrian feels under the fingers and in the heart

The first time you run a B Locrian scale slowly on your Bb clarinet, it might feel wrong, like the phrase is constantly trying to go somewhere else and never quite arriving. That is exactly the point. Locrian is music's version of a question that refuses to be answered.

Emotionally, it carries a charge of:

- Uncertainty: the flattened fifth between B and F feels like a tight rope walk.

- Suspense: the half step from B to C sounds like a breath held too long.

- Restraint: it never settles into the comfort of a solid major or minor chord.

On the clarinet, that means a chance to work on your soft attacks, your voicing, and your ability to shape long lines that never quite resolve. Players like Giora Feidman show how powerful this is: he can sit on a dissonant note for what feels like forever, using breath, vibrato, and timbre to make tension itself feel beautiful.

Practicing B Locrian is less about getting faster, and more about learning how to breathe, how to shade dynamics, and how to color each dissonant note like a painter choosing darker pigments on the palette.

Why this scale matters for your clarinet playing

You might not play a piece that literally says “B Locrian” at the top of the page, but mastering this scale on Bb clarinet quietly prepares you for music you will absolutely meet.

For classical players, it sharpens your ear for the diminished and half diminished chords that appear in Mozart cadenzas, Brahms development sections, and the spidery lines of Jean Francaix‘s Clarinet Concerto. The more comfortable you are on Locrian shapes, the more confidently you will phrase those moments instead of just “surviving” them.

For jazz players, B Locrian is the friend of every ii half diminished chord leading to a V7. If you ever improvise on a tune like “Stella by Starlight” or “My Funny Valentine” and encounter a B half diminished chord, that Locrian sound is waiting for you. It is the raw material for lines you hear in recordings by Don Byron, Eddie Daniels, and Anat Cohen.

For klezmer and folk players, Locrian colors give you new ways to bend around the “freygish” and other modes that already color that music. It is another shade of sadness, another flavor of yearning you can carry in your ornaments, trills, and bends.

| Scale Type | Emotional Color | Common Clarinet Use |

|---|---|---|

| C Major | Bright, open, stable | Melodies in Mozart and early Weber |

| B Harmonic Minor | Dramatic, lyrical | Brahms and late romantic solos |

| B Locrian | Unstable, tense, mysterious | Dissonant runs, modern and jazz passages |

Quick technical notes and fingering hints

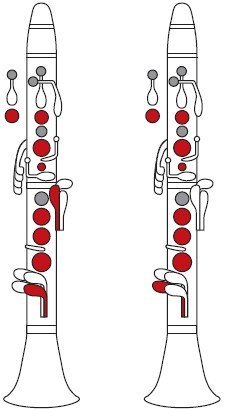

The free fingering chart gives you every note of the B Locrian scale on Bb clarinet clearly, so you do not need a long technical breakdown here. Still, a couple of ideas make it feel smoother under your hands.

B Locrian uses the same pitch collection as C major, but centered on B. That means familiar C major fingerings: open G, long B, throat tones like A and Bb, and the clarion C and D. The difference is how you group and start them. Think in patterns:

- Start on low B (in staff), using long B fingering.

- Move stepwise up to C, D, E, F, G, A, then back to B.

- Repeat the same idea in the clarion register, from B above the staff.

| Position | Approx. Tempo | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Low B to middle B | Quarter note = 60 | Smooth cross over the break and intonation on F |

| Middle B to high B | Quarter note = 72 | Even finger motion and embouchure stability |

Practice ideas with the B Locrian scale

To make B Locrian part of your musical voice, treat it like a color you are learning to mix, not just a pattern to memorize. Here is a simple practice routine you can adapt.

| Exercise | Time | How Often |

|---|---|---|

| Slow B Locrian, two octaves, legato | 5 minutes | Daily, before etudes |

| Broken thirds through the scale | 5 minutes | 3 days per week |

| Improvise a 16 bar “suspense” solo using only B Locrian | 10 minutes | 1 to 2 days per week |

Pair this with a quick review of more straightforward material, such as a G major scale fingering chart for Bb clarinet or a long tone exercise routine. Switching between stable major sounds and B Locrian helps your ear really hear the difference.

Key Takeaways

- The B Locrian scale on Bb clarinet trains your ear and fingers to live inside dissonance and tension with control.

- Famous clarinetists across classical, jazz, and klezmer styles use Locrian-like colors in concertos, solos, and improvisations.

- A few minutes of focused B Locrian practice supports harder music, from Brahms and Shostakovich to jazz standards and film scores.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet B Locrian scale fingering?

The Bb clarinet B Locrian scale fingering uses the same note set as C major, starting and ending on written B. You move stepwise from B to C, D, E, F, G, A, and back to B across two octaves. Our free clarinet fingering chart shows each note clearly to keep fingerings simple.

Why should I practice the B Locrian scale on Bb clarinet?

Practicing B Locrian helps you handle dissonant intervals found in half diminished chords, diminished arpeggios, and modern clarinet writing. It improves intonation on sensitive notes like written F and B, and prepares you for advanced orchestra parts, jazz solos, and contemporary chamber music passages.

Which clarinet pieces benefit from B Locrian practice?

B Locrian practice supports challenging moments in works like Weber's concertos, Brahms's Clarinet Quintet, Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time, and Adams's Gnarly Buttons. It also helps with jazz standards using half diminished chords and with contemporary pieces recorded by Martin Frost, Sabine Meyer, and David Krakauer.

How often should I include B Locrian in my practice routine?

Five to ten minutes a day is enough for most clarinetists. Run the B Locrian scale slowly in two octaves, then add simple patterns like broken thirds. Combine this with long tones and a more familiar key, such as G major or F major, for a balanced daily routine.

Is B Locrian too advanced for beginner clarinet players?

Beginners can absolutely experiment with B Locrian, especially if they already know a C major scale. Since the fingerings match C major on Bb clarinet, the challenge is mostly in listening and phrasing. Using our free fingering chart, even early students can start exploring the sound without feeling overwhelmed.