If you started clarinet on a plastic student horn in a school band room, there is a good chance your first victory song was “Three Blind Mice.” For Bb clarinet players, this tiny melody is like a doorway: only three notes, yet it carries centuries of stories, jokes, protests, playground rhymes, and a surprising amount of musical soul.

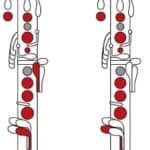

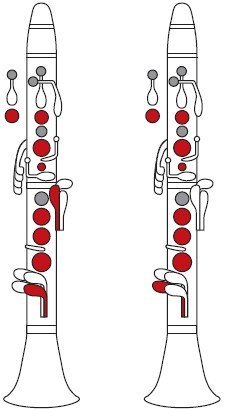

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

Learning “Three Blind Mice” on clarinet is more than just matching fingers to a simple Bb clarinet fingering chart. It is your first taste of phrasing, breathing, and tone color. Those three descending notes teach you how to make the clarinet speak like a voice instead of a machine.

The Three Blind Mice clarinet fingering chart is a beginner-friendly Bb clarinet guide that shows fingerings for the three main notes in the melody, usually G, F, and E. It helps new players build confidence, refine tone, and practice musical phrasing with a familiar song.

The quiet power of Three Blind Mice on clarinet

On paper, “Three Blind Mice” is almost comically simple: just a short descending line, like a child sliding down a playground slide. But the first time you play it on a Bb clarinet, you feel something different. The reed vibrates, the bell gently projects that falling melody, and a simple nursery rhyme suddenly carries weight.

Clarinet legends had early moments like this too. Imagine a very young Benny Goodman in Chicago, before the famous Carnegie Hall concert, wrestling with his first tunes on a battered wooden clarinet. Or Sabine Meyer as a child in Crailsheim, playing basic songs to learn breath control long before tackling the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. Their beginnings probably looked a lot like yours: short tunes, slow fingers, and a melody as plain as “Three Blind Mice.”

Most versions of Three Blind Mice for Bb clarinet sit on just 3 primary notes: G, F, and E in the middle register. Those notes also anchor countless band pieces, Mozart excerpts, and simple jazz riffs you will meet later.

How the great clarinetists started with simple songs

The names we associate with virtuosity rarely get linked to nursery rhymes, but every master of clarinet tone spent years with short tunes just like “Three Blind Mice.” The difference is what they did with them.

Anton Stadler, the clarinetist who inspired Mozart to write his legendary Clarinet Concerto in A major K. 622, would have trained his breath support and embouchure on easy, chant-like melodies in his youth. Those early exercises shaped the round, vocal sound Mozart loved so much that he wrote arias for clarinet instead of voice.

Heinrich Baermann, adored by Carl Maria von Weber, practiced slow songs to refine legato between notes like G, F, and E. That same smooth connection appears in Weber's Concertino in E b major Op. 26, where descending figures flow with exactly the same shape as “Three Blind Mice,” only stretched, ornamented, and harmonically colored.

Jump forward to the 20th century. Sabine Meyer, famous for her crystalline sound in the Berlin Philharmonic and her recordings of the Mozart and Brahms Clarinet Quintets, talks often about shaping even the smallest phrase, no matter how basic. If she played “Three Blind Mice” today on her Buffet-Crampon clarinet, you would hear a line as carefully sculpted as a phrase in Brahms's Clarinet Trio in A minor Op. 114.

Martin Fröst, with his wild stage energy and recordings of pieces like Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales,” built his flexibility by learning to bend the simplest tunes. Glissandi, dynamic swells, gentle vibrato on sustained notes: they all begin with a short pattern you repeat until it feels like speech. “Three Blind Mice” fits that job perfectly.

And in jazz, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Buddy DeFranco did their own version of this. Before improvising on “Sing, Sing, Sing” or “Star Dust,” they worked over basic licks, often built on falling patterns like G-F-E. These tiny shapes show up in their solos, just faster and with more swagger.

From nursery rhyme to history lesson: where Three Blind Mice came from

“Three Blind Mice” sounds harmless, but its story has sharp edges. The earliest printed music for the tune appeared in England in the early 1600s. Some historians link the text to dark political satire about the reign of Queen Mary I. That playful little line you are learning on clarinet once carried coded criticism and risk.

Over the centuries, the melody left court gossip behind and landed in children's books, piano primers, and folk song collections across Europe and North America. Singing families turned it into a round, much like “Frere Jacques.” Street organ players in London cranked out its jaunty rhythm. Fiddlers and flutists used it to warm up before dances.

By the time the clarinet gained real prominence through composers like Mozart, Weber, and Brahms, “Three Blind Mice” was already a familiar tune. Music teachers grabbed it instantly for beginners. It fit the early range of the Bb clarinet, sat nicely under the left hand, and helped teach players to move cleanly from open G to covered tone holes.

By the 20th century, as school bands exploded in number, band directors needed simple, recognizable songs. “Three Blind Mice” found a new home in clarinet section warmups, printed method books, and early recorder and clarinet classes. Its journey from political joke to band-room staple is surprisingly long and colorful.

Where the spirit of Three Blind Mice hides in famous clarinet music

You might not hear the full tune in a symphony hall, but the flavor of “Three Blind Mice” is everywhere: that simple downward stepwise motion, gently leaning into a cadence. Once you notice it, you start hearing it inside major clarinet repertoire.

In Mozart's Clarinet Concerto, the slow movement in D major is full of falling stepwise lines that could be cousins of “Three Blind Mice.” The clarinet glides down by seconds, often in groups of three or four notes, asking for the same breath support and smooth fingers you practice in this nursery tune.

Weber's Clarinet Concerto No. 2 in E b major has moments in the Romanze where the clarinet gently descends like a sigh. Those passages are essentially “Three Blind Mice” dressed in elegant clothes: same direction, same gravity, different harmony.

In Brahms's Clarinet Sonatas Op. 120, especially the E b major Sonata No. 2, the opening clarinet line moves in small steps that feel like a grown-up version of that childhood descent. You can practice those Brahms phrases by first playing “Three Blind Mice” slowly, focusing on even finger motion from G to F to E, then applying the same care to Brahms's longer lines.

Jazz clarinetists use the contour constantly. Listen to Benny Goodman on “Body and Soul” or Artie Shaw on “Begin the Beguine.” Between the flashy arpeggios, you will find short, sighing descents, often just three or four notes. These are the “Three Blind Mice” cells dressed in swing rhythm and jazz harmony.

Klezmer artists like Giora Feidman and David Krakauer also lean heavily on this type of motion. In traditional freylekhs and horas, the clarinet often slides down a scale, sometimes with a bend or a sob at the end. That emotional dip is exactly what you feel when you shape “Three Blind Mice” with a tiny decrescendo and a gentle breath release.

Film composers know this trick well. Listen to John Williams writing for clarinet in soundtracks like “E.T.” or “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone.” When the clarinet paints a nostalgic or childlike moment, it often walks down the scale in two or three steps, echoing that same familiar contour.

| Piece | Composer / Player | Three Blind Mice connection |

|---|---|---|

| Clarinet Concerto in A major | W. A. Mozart / Anton Stadler | Slow movement phrases use gentle stepwise descents like the song's three-note fall. |

| Concerto No. 2 in E b major | Carl Maria von Weber / Heinrich Baermann | Romantic sighing lines echo the contour of G-F-E in expressive legato form. |

| Jazz standards (Body and Soul, Star Dust) | Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Buddy DeFranco | Short descending licks often compress into a familiar three-note fall. |

Why Three Blind Mice feels so human on clarinet

On voice, “Three Blind Mice” can sound playful. On clarinet, it can sound tender, even a little sad, depending on your air and embouchure. That falling line naturally leans toward softness, like a question trailing off or a sigh at the end of a long day.

This is why teachers love it. Those three notes let you experiment: try a brighter tone near the barrel joint, then a warmer, covered sound by relaxing your throat. Shape the phrase with a slight crescendo on the first note, then gently release toward the last. In a few seconds, you are not just playing a tune. You are shaping a tiny emotion.

For many young players, the first time a parent looks up and says, “Oh, that actually sounds beautiful” happens on a piece this simple. Not on a high-speed étude, not on a clarinet choir arrangement of a film score, but on a slow, clear version of “Three Blind Mice” with a centered tone and smooth fingers.

What mastering Three Blind Mice does for your clarinet journey

So why does a clarinetist who dreams of Rhapsody in Blue or Klezmer wedding solos spend time on “Three Blind Mice”? Because this tiny song quietly trains nearly everything you need.

- It locks in your left-hand basics: thumb hole, first three fingers, and the balance of the instrument.

- It trains your ear to hear stepwise motion in G major or C major, depending on the arrangement.

- It teaches you how to start and end a phrase cleanly with your tongue, using the tip on the reed, not the side.

- It invites you to experiment with dynamics: start mezzo-piano, end piano, or reverse it.

Those same skills transfer directly to more advanced music. The way you move from open G to F and E in “Three Blind Mice” is the way you will later move through passages in the Weber Concertino or Debussy's Première Rhapsodie. The way you breathe for one short line now prepares you for longer arches in the Brahms Clarinet Quintet Op. 115.

Spending just 5 focused minutes a day on Three Blind Mice, with a tuner and slow air, can noticeably improve tone stability and finger coordination over only 2 weeks.

Creative ways the masters would practice Three Blind Mice

If you handed this melody to Richard Stoltzman or Martin Fröst, they would not shrug. They would play with it. That is your invitation too. Treat “Three Blind Mice” as a tiny improvisation lab for your Bb clarinet.

- Change articulation: try legato, then all staccato, then a mix (first long, next two short).

- Shift registers: play it in the low chalumeau register (low G, F, E) and then in the clarion register (higher D, C, B).

- Vary rhythm: turn the straight eighth notes into swung rhythms, like Benny Goodman would.

- Transpose: move the tune to different starting notes, like A-F#-E or C-B-A to feel new fingerings.

| Version | Starting note | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Standard middle register | G (left hand, open) | Builds early comfort on thumb and top three fingers. |

| Low chalumeau version | Low G (right hand, near bell) | Trains warm tone and hand balance in the low register. |

| Clarion register version | High D (register key + A key) | Introduces register key coordination and steady air support. |

A simple Three Blind Mice clarinet practice routine

Use the free Three Blind Mice clarinet fingering chart as your map, then try this short routine 3 times a week. Keep your Martin Freres or other clarinet assembled, reed moist, and tuner nearby.

| Step | Time | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Long tones on G, F, E | 3 minutes | Steady air, centered pitch, relaxed throat. |

| 2. Play the tune slowly | 4 minutes | Finger accuracy and soft, clean tonguing. |

| 3. Change articulation | 3 minutes | Staccato, legato, mixed patterns. |

| 4. Transpose once | 3 minutes | Try a new starting note using the same contour. |

Quick fingering notes for Three Blind Mice on Bb clarinet

The free clarinet fingering chart that comes with this article shows each note with clear diagrams, so you do not need a long technical breakdown. In most beginner arrangements, you will use middle register G, F, and E.

- G: Thumb on the back hole, first three fingers of the left hand up top, no right-hand fingers.

- F: Same as G, then gently add the first finger of the right hand.

- E: Thumb, three left-hand fingers, and first two right-hand fingers.

Keep your fingers curved and close to the keys, and let the descent from G to F to E feel like a single breath. Your clarinet bell, barrel, and mouthpiece are all part of the same singing line.

Key Takeaways

- Three Blind Mice trains core clarinet skills like left-hand control, air support, and smooth legato on just three notes.

- The song's simple descending shape appears in clarinet masterpieces by Mozart, Weber, Brahms, and jazz and klezmer solos.

- Using the free fingering chart and a short practice routine turns this nursery tune into a powerful musical study.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Three Blind Mice clarinet fingering chart?

The Three Blind Mice clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide for Bb clarinet that shows which keys and tone holes to press for each note of the melody, usually G, F, and E. It helps beginners read notes faster, build steady tone, and enjoy a familiar song while learning basic technique.

Is Three Blind Mice good for beginner clarinet players?

Yes. Three Blind Mice is ideal for beginners because it stays in a comfortable range and uses only a few simple fingerings. Those same notes appear in early band pieces and classical excerpts, so mastering this tune builds confidence and prepares you for more advanced music.

Which notes are used in Three Blind Mice for Bb clarinet?

Most beginner versions use three primary notes in the middle register: G, F, and E. Some arrangements add D or C to extend the line. These notes sit under the left hand and first two right-hand fingers, so they are perfect for training hand position and smooth transitions.

How should I practice Three Blind Mice to improve my tone?

Start with long tones on each note, then play the melody slowly with a tuner. Focus on steady air from your diaphragm, relaxed shoulders, and a firm but comfortable embouchure on the mouthpiece and reed. Add soft dynamics and legato to turn the short tune into a singing phrase.

Can I use Three Blind Mice to learn other clarinet styles?

Absolutely. You can swing the rhythm for a jazz feel like Benny Goodman, add slides and small bends for a klezmer color inspired by Giora Feidman, or shape long, expressive lines as in Mozart and Brahms. The simple contour makes it a great laboratory for many styles.