If you have ever listened to a clarinet line that felt like it was floating in mid-air, never quite landing, there is a good chance an A whole-tone scale was hiding inside that sound. On Bb clarinet it feels like stepping off a staircase and discovering the floor has turned into clouds.

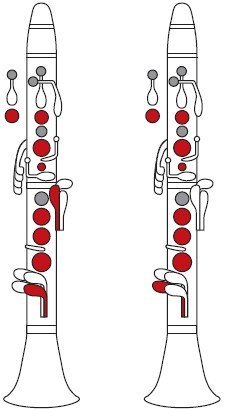

Receive a free PDF of the chart with clarinet fingering diagrams for every note!

The Bb clarinet A whole-tone scale fingering is a pattern of alternating standard and extended fingerings that produces A, B, C#, D#, F and G on the clarinet. It is built only from whole steps and creates a dreamy, floating sound that helps clarinetists shape magical colors and contemporary effects.

The dreamy pull of the A whole-tone scale on clarinet

The A whole-tone scale has only six notes: A, B, C#, D#, F and G. No half steps, no leading tones, just equal steps into the horizon. On Bb clarinet that sound can feel like a Debussy prelude sneaking into your practice room, even if you are just warming up with long tones and a tuner.

Claude Debussy loved this sound. Listen to “Prelude a l'apres-midi d'un faune” or “La Mer” and you can almost hear a ghost clarinet weaving whole-tone fragments between the flutes and oboes. Clarinetists like Sabine Meyer and Martin Frost lean into those colors whenever whole-tone moments appear, stretching the line until it almost melts. That same color is inside your A whole-tone scale. You are not just drilling a pattern. You are borrowing a paintbrush from Debussy.

The A whole-tone scale uses only six distinct notes before it repeats. That symmetry gives clarinetists a smooth, sliding quality that works beautifully for glissandi, modern jazz runs and dreamy orchestral solos.

From early clarinet voices to Debussy dreams and beyond

The seed of the A whole-tone scale was already there in the early days of the clarinet, even if players like Anton Stadler and Heinrich Baermann did not think of it in modern scale terms. Their boxwood clarinets with simple Albert-style keywork could still trace whole-step patterns, especially in high lyrical passages of Mozart's Clarinet Concerto in A major, K. 622, or Weber's Clarinet Concerto no. 1 in F minor.

Classical composers flirted with the effect in passing. You hear hints in the chromatic sighs in Carl Maria von Weber's Concertino, in the arpeggio figures of Brahms's Clarinet Sonata in F minor op. 120 no. 1, and in the cadenza-like phrases in Spohr's clarinet concertos. The instrument evolved: extra trill keys, the Boehm system, better pads and registers. Suddenly clarinetists could glide through symmetrical patterns like the A whole-tone scale with far more security and color.

The true love affair began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Alexander Scriabin and later Olivier Messiaen were all drawn to the otherworldly pull of whole-tone harmony. While Debussy wrote more standout flute and oboe solos, the clarinet in his orchestral works, such as “Images” and “Nocturnes”, often completes whole-tone chords, sliding through notes of that very A whole-tone pattern.

French clarinetists like Louis Cahuzac and Paul Meyer carried this language into their approach to Debussy, Ravel and Messiaen. Their control of soft dynamics in the chalumeau and clarion registers makes a simple A whole-tone fragment shimmer like light on water. When you practice the scale quietly, with a focused embouchure and relaxed right hand pinky keys, you are stepping into that same aesthetic.

Clarinet legends who played with whole-tone fire

Ask a jazz clarinetist about the A whole-tone scale and watch their eyes light up. Benny Goodman used whole-tone patterns constantly in his solos on tunes like “Stompin' at the Savoy” and “After You've Gone”. In fast passages over a dominant chord, you can almost sing his A whole-tone motives, sliding over the break with a relaxed right hand and crisp articulation.

Artie Shaw took it even further. Listen to his recordings of “Concerto for Clarinet” and “Begin the Beguine”. The wild, spiraling lines often include symmetrical runs that hint at whole-tone collections. The combination of a crystal-clear mouthpiece, soft cane reeds, and a flexible jaw allowed him to smear those patterns in a way that still feels modern.

Modern jazz clarinetists such as Anat Cohen and Ken Peplowski use the A whole-tone scale like a spice rack. In a solo over an A7 chord they might jump straight into an A whole-tone run to create tension, then resolve to D major or D minor. Their fingers climb past the register key without fear, because these patterns have become second nature, almost like visual shapes on the keys rather than isolated notes.

On the classical side, Sabine Meyer gives beautiful examples in recordings of the Debussy Rhapsodie and Messiaen's “Quatuor pour la fin du temps”. In the movement “Abime des oiseaux” the extended clarinet solo is not literally whole-tone, but the floating intervals often give the same suspended feeling. Martin Frost, in pieces like Anders Hillborg's “Peacock Tales”, uses whole-tone fragments in extreme dynamics and theatrical gestures, twisting his Buffet clarinet and bending pitches with embouchure and right hand fingers to make the scale sound like a living creature.

Klezmer players feel the lure as well. Giora Feidman and David Krakauer sometimes slide across segments of a whole-tone scale in high, wailing ornaments, especially over dominant chords in freygish modes. The combination of fast ornamentation, half-hole throat notes and expressive pitch bends turns the theoretical A whole-tone idea into raw emotion.

| Player | Style | Whole-tone flavor |

|---|---|---|

| Benny Goodman | Swing / big band | Fast A whole-tone runs over dominant chords in solos |

| Sabine Meyer | Classical / orchestral | Soft, floating phrases in Debussy and Ravel textures |

| Giora Feidman | Klezmer | Expressive slides across whole-tone fragments in high register |

| Martin Frost | Contemporary solo | Theatrical use of symmetrical runs in works like “Peacock Tales” |

Iconic pieces where the A whole-tone color shines

You may not see the title “A Whole-Tone Scale” in your clarinet part, but the sound is everywhere. In Ravel's “Daphnis et Chloe” and “Rhapsodie espagnole”, the clarinets often help form whole-tone chords that shimmer under the strings. A and B in the clarion register, fingered with left-hand index and the register key, become part of a magical cloud of sound.

In Stravinsky's “The Firebird” and “Petrushka”, the clarinet lines sometimes sketch symmetrical patterns that feel like whole-tone clusters. The famous solo in “L'Histoire du Soldat” plays with similar colors when the clarinet dances above the violin and bass. Modern orchestras such as the Berlin Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra have recorded these works with clarinetists like Wenzel Fuchs and Andrew Marriner shaping those patterns with laser control of air and voicing.

Film composers loved this color too. Listen for whole-tone sweeps in the clarinet sections of John Williams scores like “Harry Potter” or “War of the Worlds”. Hans Zimmer uses synthetic and sampled clarinets with whole-tone lines in soundtracks such as “Inception” to create a feeling of time bending. Even if the scale is hidden under sound design, the DNA of that A whole-tone collection is in the texture.

In chamber music, works by Bela Bartok, Paul Hindemith and Igor Stravinsky often give the clarinetist chances to spin whole-tone fragments. Bartok's “Contrasts” for clarinet, violin and piano pushes the instrument through jagged but symmetrical patterns, where an A whole-tone run can cut through the ensemble like glass.

For solo clarinet, look to modern pieces by composers like Edison Denisov, Jorg Widmann and John Adams. In Widmann's solo piece “Fantasie” the clarinet slides across symmetrical scales using flutter tongue, multiphonics and overblowing. A whole-tone segment in the altissimo register suddenly becomes a dramatic shout instead of a study pattern.

On Martin Freres, you can find stories about historical clarinets used in French conservatories where these very works were shaped and taught. Articles on their site that discuss classical clarinet embouchure, modern mouthpiece design, and historical clarinet models are all part of the background to how players approach scales like this one today.

How the A whole-tone scale feels under the fingers and in the heart

The A whole-tone scale has a strange emotional trick. It sounds both bright and unstable, like a sunrise that never becomes full day. Without half steps or a leading tone, your ear never quite knows where home is. On clarinet that quality is amplified by the instrument's smooth legato and responsive tone holes.

Play the A whole-tone scale slowly in the chalumeau register, starting on low A with a rich, dark embouchure. As you move up to B and C#, your fingers cross the break and your throat tones open. The sound becomes clearer, almost glassy. By the time you hit F and G in the clarion register, the scale feels like light poured through stained glass. Many players describe it as dreamy, mysterious or even slightly hypnotic.

This is why composers love it for magic, dreams, water, and anything that feels like a spell. Clarinetists can change that mood with articulation and dynamics. Whispered whole-tone lines with soft tongue and gentle vibrato can feel like a faraway memory, while accented, fast A whole-tone runs in the altissimo register can sound like alarms or sci-fi effects.

Why the A whole-tone scale matters for you, right now

You might be a student still wrestling with throat A and B, or a professional working on glissandi between high F and G. Either way, this scale is more than a technical exercise. It is a doorway into color. Working on the A whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet strengthens your finger confidence across the break, improves your ear for symmetrical harmony, and gives you a quick way to sound more sophisticated in both jazz and classical improvisation.

For improvisers, this scale is a secret weapon on dominant chords like A7 or G7. Slide into it over a backing track and you immediately sound more modern. For orchestral players, understanding this sound lets you tune and balance whole-tone chords in Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky more intelligently. For klezmer or folk clarinetists, it offers fresh ornaments and transitions between modal phrases.

Martin Freres often writes about the musical life of the clarinet, from historical French makers to modern pedagogy. Articles on their site about clarinet tone production, register transitions and historical repertoire all connect to this same goal: helping you turn scales like A whole-tone into expressive tools, not just exercises.

Key Takeaways

- Treat the A whole-tone scale as a color palette for jazz lines, impressionistic solos and film-style effects on clarinet.

- Practice it across dynamics and articulations to feel how it shifts from dreamy and soft to bright and edgy.

- Listen to clarinet greats in classical, jazz and klezmer recordings, then imitate how they use whole-tone fragments in real music.

A light technical look: A whole-tone scale on Bb clarinet

The fingering chart you can download will show every note of the A whole-tone scale clearly, but it helps to have a mental picture. On Bb clarinet the basic six-note pattern is A, B, C#, D#, F and G, then back to A. You cross the break early, moving from chalumeau to clarion with minimal hand shifts.

Most fingerings are standard: low A with left-hand fingers 1-3 and right-hand 1-3, B with register key and left-hand 1, C# with left-hand 1-2 and right-hand 2, then into D# with right-hand pinky and the usual clarion configuration. The only real challenge is keeping the throat tones, especially A and B, as full as your chalumeau notes. A steady airstream and relaxed embouchure do more for this scale than any exotic alternate fingering.

Simple practice ideas to make the scale sing

Think of your practice as story-building rather than box-checking. Here are a few gentle structures to help your A whole-tone scale grow into something musical.

- Play the A whole-tone scale very slowly, two octaves if you can, using a tuner. Focus on centered throat notes and smooth crossing of the break.

- Change dynamics: one time crescendo from low A to high A, next time reverse it. Feel how the scale's mood shifts with air and embouchure.

- Improvise a 4-bar melody using only the A whole-tone notes. Record yourself, then try again with different articulation patterns.

- Alternate A whole-tone with a regular A major scale. Notice how your ear reacts to the missing half steps.

| Day | Activity | Suggested time |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Slow A whole-tone scale, legato, focus on tone | 5 minutes |

| Day 2 | Staccato patterns using the same notes | 5 minutes |

| Day 3 | Improvise 8 bars over a backing A7 chord | 5 minutes |

| Day 4 | Contrast A whole-tone with A major and A minor | 5 minutes |

| Issue | Likely cause | Quick fix |

|---|---|---|

| Thin throat A and B | Weak air support or tight embouchure | Blow a bit faster air, relax jaw, keep tongue low like saying “ah” |

| Bump at the break | Fingers lifting unevenly between A and C# | Isolate A-B-C# slowly with continuous air, watch left-hand fingers |

| Pitch sag on F and G | Low tongue position or heavy lower lip | Think “ee” inside mouth, slightly lighten lower lip pressure |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bb clarinet A whole-tone scale fingering?

The Bb clarinet A whole-tone scale fingering is the pattern that produces A, B, C#, D#, F and G using mostly standard fingerings across chalumeau and clarion registers. The scale moves only in whole steps, giving a smooth, floating sound that is ideal for jazz lines, orchestral colors and modern effects.

Why does the A whole-tone scale sound so dreamy on clarinet?

The A whole-tone scale has no half steps or leading tones, so your ear never hears strong resolution. On clarinet, with its smooth legato and flexible embouchure, those equal steps blend into a cloud-like sonority. That is why composers use it for magic, dreams, water imagery and mysterious transitions in scores.

How can I use the A whole-tone scale in jazz improvisation?

In jazz, the A whole-tone scale works beautifully over A7, E7 and G7 type chords. You can run the scale ascending or descending, use small patterns of three or four notes, or sequence it in different rhythms. Clarinetists like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw often used similar whole-tone runs to create tension before resolving to diatonic melodies.

Is the A whole-tone scale only for advanced clarinet players?

No. Even early intermediate players can explore it slowly. The fingerings are mostly standard, so the main tasks are steady air and smooth crossing of the break. Start in one octave, play it as a gentle warm-up, and then gradually add range and speed as your comfort with throat notes and clarion register grows.

How should I practice the A whole-tone scale to improve tone?

Use long tones on each note of the scale, with a tuner, and listen carefully to the color of your sound. Begin softly, then add crescendos and decrescendos on each note. Focus on matching tone quality from chalumeau A up to clarion F and G. This simple process strengthens embouchure, breath control and evenness across registers.