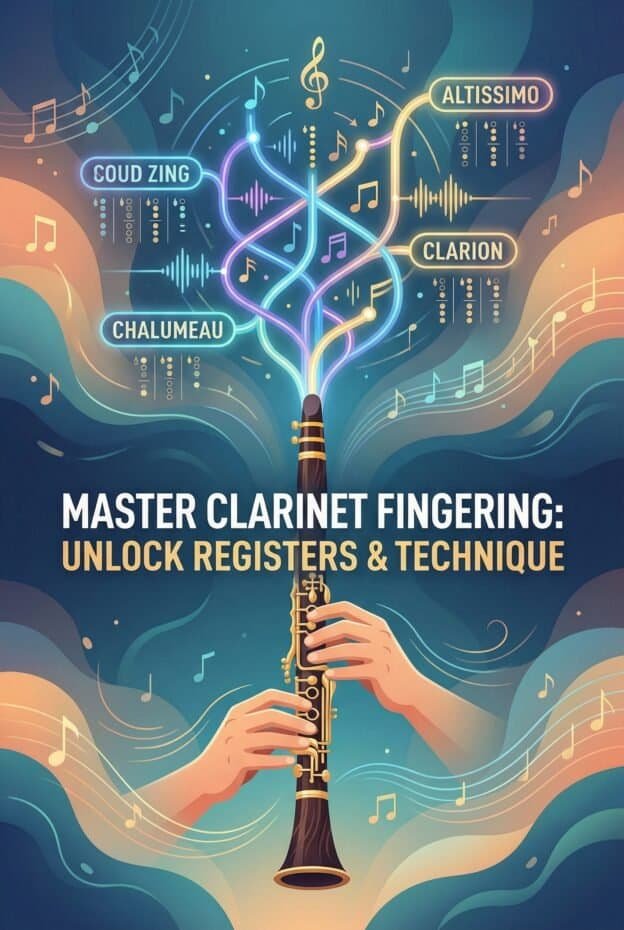

The Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart is a complete note-to-fingering map for clarinetists. Use it to learn standard fingerings across registers (chalumeau, clarion, altissimo), practice smooth register shifts, and troubleshoot pitch and response issues by matching note, fingering, and embouchure adjustments.

What is the Martin Freres Clarinet Fingering Chart?

The Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart is a visual guide that shows which keys and holes to cover for every written note on the clarinet. It maps fingers to notes across all registers, from low E to high altissimo, and often includes alternate fingerings for tuning, response, and technical ease in fast passages.

Unlike a generic chart, a Martin Freres chart is designed as a practice tool, not just a poster. It helps you see how finger patterns repeat between registers, where the register key changes the pitch, and which alternate fingerings work best for specific musical situations, such as trills, soft attacks, or sharp/flat notes.

For teachers and technicians, the chart also acts as a diagnostic reference. When a note misbehaves, you can compare the written fingering, the actual sound, and the instrument setup to decide whether the problem is technique, reed, or a mechanical fault such as a pad leak or misaligned key.

Quick Clarinet Anatomy: Parts That Affect Fingering

To use any fingering chart well, you need a basic map of the clarinet body. The main parts that affect fingering are the mouthpiece, barrel, upper joint, lower joint, and bell. The keys, rings, and tone holes on the upper and lower joints are what the chart diagrams for each written note.

The left hand sits on the upper joint. It controls the thumb hole and register key on the back, plus three main tone holes and surrounding rings on the front. The right hand sits on the lower joint, using three main fingers and the pinky keys that reach low E, F, and related notes. The thumb rest supports the right hand.

The register key (often called the speaker key) is important. It vents a small hole in the upper joint to shift many notes up by a twelfth. On a fingering chart, it is usually marked with a special symbol or a separate icon near the left thumb, since it changes the register without changing most other fingers.

Tone holes and rings work together. When you press a ring key, you close a hidden pad and sometimes also seal the ring around a tone hole. This combination affects tuning and response. Alternate fingerings often use different ring combinations to slightly lengthen or shorten the air column for sharper or flatter pitches.

The bore (the inner tube of the clarinet) and the bell shape influence how low notes speak. If the bell or lower joint has leaks or damage, low E, F, and F sharp become unreliable even with correct fingering. Understanding this anatomy helps you decide whether a fingering problem is really a mechanical or maintenance issue.

Understanding Clarinet Registers and How the Chart Maps Them

Clarinet fingering charts usually divide notes into three main registers: chalumeau, clarion, and altissimo. The chalumeau register is the low register, from written E below the staff up to about B flat above middle C. These notes use the left thumb hole without the register key and form the foundation of basic finger patterns.

The clarion register starts when you add the register key. Most fingerings from low chalumeau notes are reused, but the register key raises them by a twelfth. For example, low F with the register key becomes written C above the staff. On the chart, you will see nearly identical finger patterns, with the register key symbol added for clarion notes.

The altissimo register extends above the clarion, starting around written C sharp or D above the staff. Altissimo fingerings are less standardized. A good chart, such as a detailed Martin Freres reference, will show several options for many altissimo notes, often labeled as primary, alternate, or tuning variants.

On a well-designed chart, each register is grouped visually. Colors, labels, or staff diagrams show where chalumeau ends and clarion begins. This helps you see how the same left-hand pattern appears in different registers. When you learn to read the chart this way, register shifts feel like logical extensions rather than brand new fingerings.

How to Read and Use the Martin Freres Fingering Chart (Step-by-Step)

The fastest way to benefit from the Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart is to treat it like a map you revisit daily. Start by locating the staff diagram for the note you want to play. The written pitch (not sounding pitch) will be shown on a treble staff, often grouped by register or by chromatic order.

Next, look at the clarinet diagram beside that note. Closed circles or darkened keys show which tone holes and keys to press. Open circles show which to leave uncovered. The left thumb and register key are usually drawn separately on the back of the clarinet icon, so check carefully whether the register key is included.

Pay attention to any labels such as “standard”, “alternate”, or “trill”. Standard fingerings are the ones you should learn first. Alternate fingerings are useful for tuning, color, or technical passages. Trill fingerings are special combinations that allow fast alternation between two notes without moving too many fingers.

When you first learn a note, say written A above the staff, compare its fingering to the note a twelfth lower, written E in the chalumeau register. On the chart you will see that the same fingers are used, plus the register key. This visual pattern helps you memorize registers and reduces the feeling of being overwhelmed.

Step-by-step: Using the chart for a new scale

Choose a simple scale, such as G major. On the chart, find each written note of the scale in order. For each note, say the note name out loud, then trace the fingering diagram with your finger. After that, finger the note on your clarinet without playing, matching the diagram exactly.

Once you can finger the scale silently from memory, play it slowly with a tuner. If a note is sharp or flat, look back at the chart for any alternate fingering symbols. Some charts mark tuning variants with small plus or minus signs, or with notes in the legend such as “slightly flatter” or “brighter”.

Repeat this process for each new key you learn. Over time, you will not need to check every note. The chart becomes a confirmation tool when you encounter unfamiliar accidentals, altissimo notes, or awkward trills in your music. Keep a printed copy near your stand so you can glance at it during practice.

HowTo: How to use the Martin Freres fingering chart

- Identify the written note on your sheet music and locate the same note on the chart's staff diagram.

- Study the clarinet icon next to that note and note which circles or keys are filled (pressed) and which are open.

- Check for register key symbols, alternate fingering labels, or trill markings in the legend.

- Finger the note slowly on your clarinet, matching the chart exactly, then play it with a steady air stream.

- Compare the sound with a tuner; if intonation is off, test any alternate fingerings shown for that pitch.

- Integrate the new fingering into a short scale or pattern so it becomes part of your muscle memory.

Practice Routines and Exercises Based on the Fingering Chart

A fingering chart is most powerful when it shapes your daily practice. One effective routine is the “register mirror” exercise. Choose a low note, such as written F in chalumeau. Play it, then use the chart to find the corresponding clarion note with the same fingering plus register key, written C above the staff. Alternate between the two.

Use a metronome at quarter note equals 60 and play each pair as long tones. Focus on matching tone color and stability between registers. As you gain control, increase the tempo and connect the notes legato. The chart helps you see which finger patterns repeat, so you can build smooth, predictable register shifts.

Another routine is the “chromatic ladder” based on the chart. Starting from low E, move up by half steps using the chart to check each fingering. Aim for a steady tempo, such as 60, then gradually increase to 80, 100, and 120 as your accuracy improves. Mark any notes that consistently feel awkward and review their diagrams.

For altissimo, use the chart to build small three-note patterns. For example, practice written A, B flat, and B in altissimo using the recommended primary fingerings. Play them slowly, then add the same notes in clarion register. This comparison, guided by the chart, helps you connect altissimo to fingerings you already know.

Teachers can assign “chart quizzes” where students cover the note names and identify fingerings from the diagrams alone, or vice versa. This strengthens mental mapping between staff notation and hand position. Over a few weeks, students report less hesitation when reading new music because the fingerings feel more automatic.

Common Fingerings, Variants and When to Use Them

Many Martin Freres fingering charts highlight common alternate fingerings that solve real musical problems. For example, written B flat on the middle line can be played as A plus the right-hand side key, or as the first finger on the left hand plus the register key. The chart usually marks one as standard and the other as alternate.

Use the A plus side key B flat for scales and lyrical lines, since it keeps the left hand stable. Use the one-finger B flat for fast passages that move between A and B natural, or when the right-hand side key would be awkward. The chart makes this choice clear by showing both options side by side.

Another common example is written F sharp in the chalumeau register. Some charts show the standard fingering with two right-hand fingers, and an alternate with different ring combinations. The alternate may tune slightly flatter or sharper. Your chart notes which is better for sharp instruments or for soft dynamics.

In the clarion register, written C sharp and D often have several options. A good chart will show a primary fingering plus side-key variants that make trills easier. For instance, a trill between C sharp and D might use a special trill fingering that avoids large finger movements. Look for “tr” or “trill” labels on the chart.

Altissimo notes such as written E, F, and G above the staff can have three or more fingerings each. The Martin Freres chart may label them by context: one for tuning, one for legato, and one for forte attacks. Experiment with each while watching a tuner and listening for tone color. Keep a small pencil mark in your music to remind you which one you chose.

Troubleshooting: Fix Sour Notes, Squeaks and Register Breaks

When a note sounds wrong even with the correct chart fingering, you need a simple diagnostic routine. Start by checking embouchure and air. Use a firm, centered embouchure and steady air stream. Then compare the note with a tuner. If it is consistently sharp or flat, test any alternate fingerings listed on the chart for that pitch.

If a note squeaks when you cross the break between chalumeau and clarion, look closely at the chart diagrams for both notes. Often the problem is one finger lifting too early or too late. Practice the two fingerings slowly while watching your fingers, then add the register key at the exact moment shown in the chart diagram.

Some sour notes are caused by partial coverage of a tone hole. Use the chart to confirm which fingers should be down. Then, while fingering the note, gently roll each finger to feel if the pad is sealing fully. If a small movement changes the sound, you may have a hand position issue or a pad that is not seating correctly.

To test for mechanical problems, compare the same fingering on another clarinet if possible, or play the note using an alternate fingering from the chart. If the alternate works perfectly but the standard does not, you may have a leak on one of the keys used only in the standard fingering. That is a sign to see a technician.

Altissimo squeaks often come from biting or insufficient air support, but the wrong fingering can make them worse. Use the chart to find the recommended primary altissimo fingering, then practice it as a long tone at mezzo piano. If the note only speaks at very loud dynamics, consider trying one of the alternate altissimo fingerings shown.

Maintenance Steps That Improve Fingering Reliability

Even perfect use of a fingering chart cannot fix a clarinet with leaks or misaligned keys. Basic maintenance directly affects how reliably fingerings work. Regularly inspect pads for discoloration, deep impressions, or frayed edges. Pads that do not seal well cause certain chart fingerings to respond poorly or play out of tune.

A simple leak test can be done at home. Gently close a key with one hand and lightly tug a thin strip of paper between the pad and tone hole. You should feel resistance all around the pad. If the paper slides freely in one area, that pad may be leaking, which will especially affect low notes and cross-fingerings.

Check pivot screws and rod screws for excessive play. Keys that wobble can change how a fingering behaves, because the pad may not land in the same place every time. Tighten only slightly and stop if you feel resistance. For anything more than a quarter turn, consult a qualified technician to avoid damage.

Keep the tenon corks lightly greased so the joints align correctly. Misaligned joints can shift tone holes away from their ideal positions, making some chart fingerings feel inconsistent. Always assemble the clarinet with a gentle twisting motion and check that bridge keys line up cleanly between the upper and lower joints.

Plan a professional checkup at least once a year if you play regularly, or more often for intensive students. A technician can check pad seating, spring tension, and key height, all of which affect tuning and response. After service, you may find that notes that used to fight you now match the chart fingerings much more easily.

Martin Freres – Brand History and Archive Fingering References

Martin Freres has a long association with clarinet playing, especially through historical instruments and educational materials. While many players know the name from vintage clarinets, the brand's legacy also includes fingering references that reflect how clarinet pedagogy evolved from the 19th to the 20th century.

Early fingering charts, including those used with Martin Freres instruments, often followed regional systems influenced by French and German schools. Over time, these converged toward the Boehm-system standard that most modern charts follow. Comparing older charts with modern ones reveals how altissimo fingerings and tuning preferences have changed.

Researchers and enthusiasts can consult general clarinet history resources such as Grove Music Online, the National Music Museum collections, and digitized conservatory methods to see how fingering charts were presented alongside Martin Freres and other period instruments. These archival materials give context to the modern charts used by students today.

Downloadable Resources, Charts and Printables

For daily practice, a printed fingering chart near your stand is more useful than a chart buried in a book. Many players keep two versions: a full-range chart that covers chalumeau through altissimo, and a simplified beginner chart that focuses on the most common notes in school band music.

When you download a Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart, look for clear staff notation, large clarinet diagrams, and a legend that explains symbols for register key, alternates, and trills. A high-resolution PDF allows you to print at letter or A4 size without losing detail, so fingerings remain readable from your chair.

Teachers often laminate charts or place them in sheet protectors for studio use. Some create small, two-page booklets: one page for basic range, one for altissimo and alternates. Students can mark their preferred altissimo fingerings or tuning choices directly on their copy, turning the chart into a personalized reference.

Digital versions are also useful. Keeping a chart on a tablet lets you zoom in on specific notes or share screenshots with students during online lessons. Just be sure the digital chart matches the same fingering conventions you use in lessons, so students are not confused by conflicting diagrams.

Player Outcomes: What You Can Expect After Mastering the Chart

Consistent work with a fingering chart leads to measurable progress. Most students who use a structured routine with the Martin Freres chart can reliably cover a range of more than two and a half octaves within a few months, including basic altissimo notes, as long as they practice slowly and check fingerings carefully.

Speed and accuracy also improve. A realistic goal is to play a full chromatic scale from low E to high C at quarter note equals 80 in sixteenth notes with clean finger transitions. As fingerings become automatic, you can push this to 100 or 120 while keeping tone and tuning stable across registers.

Intonation tends to stabilize when you consistently choose the right variants for your instrument. By pairing the chart with a tuner, you learn which alternate fingerings bring sharp notes down or lift flat notes up. Over time, you will rely less on embouchure adjustments and more on smart fingering choices.

Musically, this control opens new repertoire. Etudes by Carl Baermann, Rose, or contemporary method writers become more approachable when you are not guessing at fingerings. Orchestral excerpts that cross the break or sit in the upper clarion register feel less intimidating because your hands know where to go without hesitation.

Key Takeaways

- The Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart is a complete map of standard and alternate fingerings across chalumeau, clarion, and altissimo registers.

- Understanding clarinet anatomy and registers helps you read the chart accurately and choose the best fingering for tone, tuning, and technical ease.

- Regular practice routines built around the chart improve range, speed, and intonation, while troubleshooting and maintenance keep fingerings reliable.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart?

The Martin Freres clarinet fingering chart is a detailed visual guide that shows which keys and tone holes to press for every written note on the clarinet. It includes standard fingerings, register-key usage, and often alternate and trill fingerings, so players can improve technique, tuning, and register control using a single reference.

How do I use the fingering chart to improve my altissimo register?

Use the chart to identify the primary and alternate fingerings for each altissimo note, then practice them as slow long tones with a tuner. Compare altissimo notes to their clarion equivalents, and test each alternate fingering for stability and tuning. Mark the ones that work best for you and use them consistently in scales and etudes.

Can I use the Martin Freres chart for Bb and A clarinets?

Yes. Fingering patterns for modern Bb and A clarinets are essentially the same, so a single chart works for both. The written notes on the staff look identical, but remember that the sounding pitch differs by a semitone. Use the same chart fingerings, and let your ear and tuner guide any small tuning adjustments.

Why does a note sound off even when I use the chart fingering?

If a note sounds off with the correct fingering, check embouchure and air first, then compare with a tuner. Try any alternate fingerings listed on the chart. If the problem persists, you may have a pad leak, misaligned key, or worn cork. In that case, a technician should inspect the instrument for mechanical issues.

Is there a printable or PDF version of the fingering chart?

Yes. Many Martin Freres fingering charts are available as printable PDF files designed for music stands or binders. Look for a high-resolution version that includes full range, clear clarinet diagrams, and a legend for alternates and trills. Printing on good-quality paper or laminating helps the chart last in daily practice.

How often should I have my clarinet checked to ensure reliable fingerings?

For regular players, a yearly checkup is a good minimum. Students practicing daily or preparing for auditions may benefit from service every 6 to 9 months. A technician can correct leaks, adjust key heights, and regulate springs so that the fingerings shown on your chart produce consistent, in-tune notes across the full range.